by Mary Howard

We were delighted to welcome first time guest hosts, Julie Wright and Barry Hoonan to our #G2great chat table on August 23, 2018. I was perched and ready with fingers resting happily on my computer keyboard well before official chat start time, eagerly anticipating a lively discussion around their amazing new book, What Are You Grouping For? How to Guide Small Groups Based on Readers – Not the Book (grades 3-8) Corwin 2018. From the first “Welcome friends,” all that the words “lively discussion” entail burst into life aka Twitter passion.

Our entire #G2Great family was excited about this chat, as evidenced by a rapid Twitter trending status. But in my case, enthusiasm was also on a personal level. Earlier this year, I was asked to consider writing the foreword for this upcoming book. I quickly flipped to the introduction – and any doubt that may have been in my mind quickly dissolved into a resounding “YES” in those first pages. It didn’t take long to recognize that the message residing at the heart of this book was desperately needed. It felt as if Julie and Barry were reading my mind as they tackled two small group concerns that have plagued me for years:

- Small groups afford time for differentiated instruction at all grade levels. As students move up the grades, however, fewer teachers make room for these opportunities. Julie and Barry provide a flexible open-ended design that will help teachers at all grade levels envision what these more versatile small groups could look like, sound like and feel like.

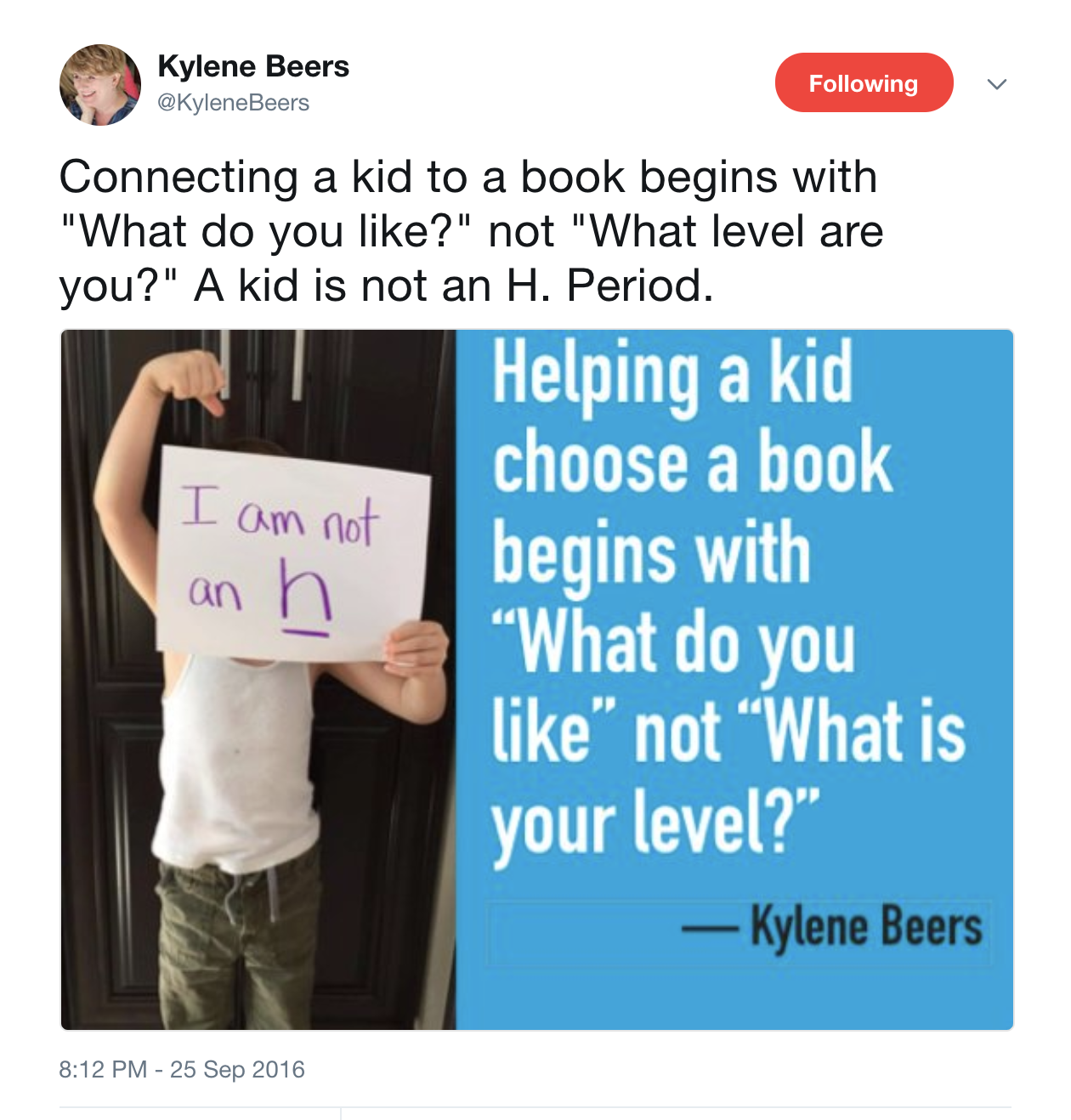

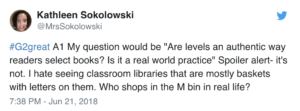

- Small groups often focus on homogeneous guided reading groups based on reading levels. Heterogeneous options they describe are the missing piece that would break free of the constraints of narrow groupings. Guided reading is an effective structure when done selectively and in the right spirit, but Julie and Barry wisely broaden this perspective in ways that will maximize our small group power potential.

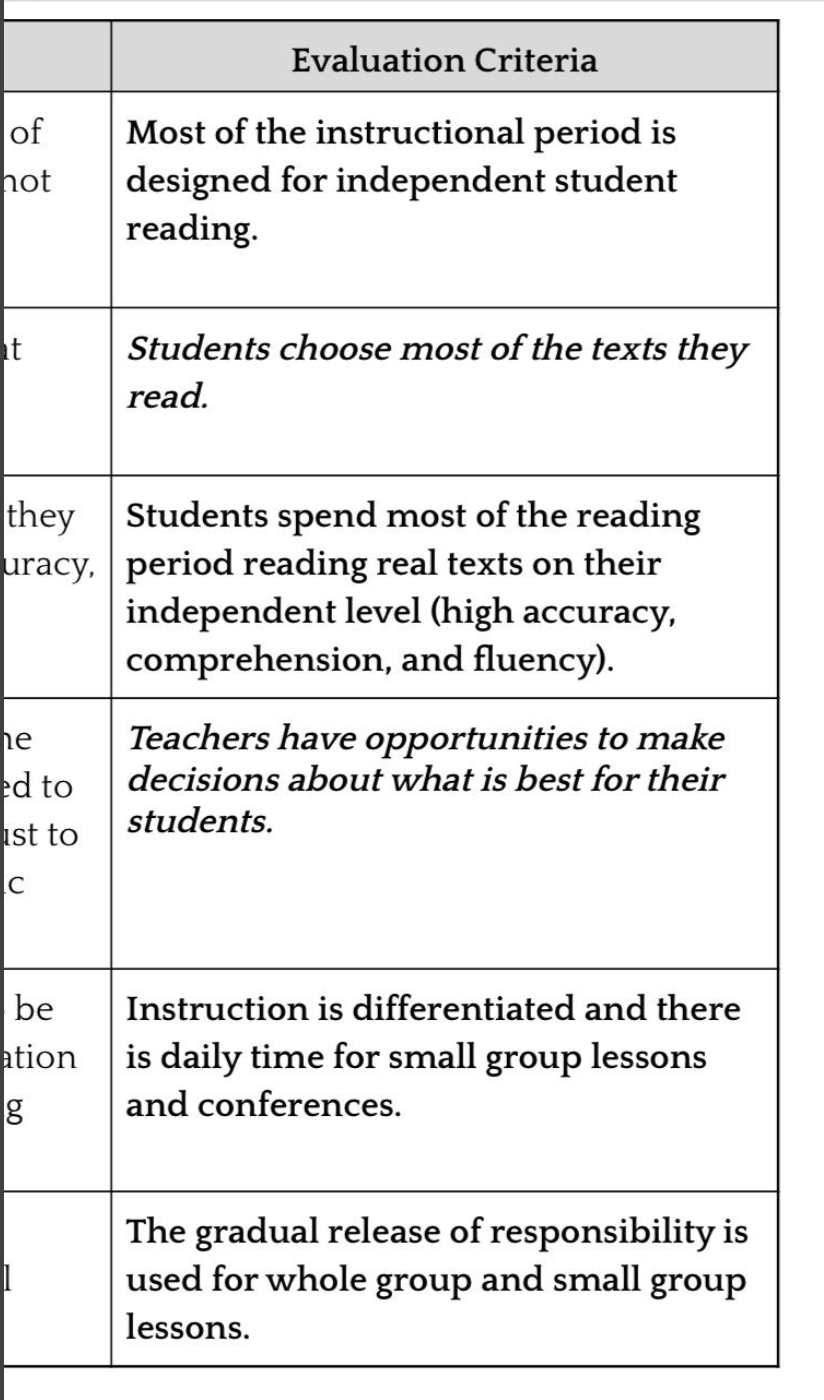

Julie and Barry support guided reading in the early grades or for striving readers across grades but they ask us to consider a small group design that will alleviate some of the control and limitations often associated with guided reading. A more expansive small group view would offer an instructional design where we can “engage, inspire, and foster collaboration with students” beyond homogeneous settings with critical additions that could even inform homogeneous experiences. They describe that redesign in this way:

“Students’ curiosity and interest are more trustworthy and energizing drivers of grouping decisions than anything else. When we harness the power of the social and personal, it becomes far easier for us to teach into their academic needs as readers.”

Julie and Barry propose responsive small groups that address both the instructional and emotional needs of children and thus are created for a variety of reasons in a variety of ways while acknowledging the tremendous role curiosity and interest play in this grouping process. They are not asking us to abandon other practices but to increase the scope of our small group lens so that the passions students carry in their back pockets can become a grouping informant to explore other options. In other words, we are not closing the door to familiar structures like guided reading, but rather wisely opening that door even wider to welcome the passion fueled groupings that have previously gone untapped.

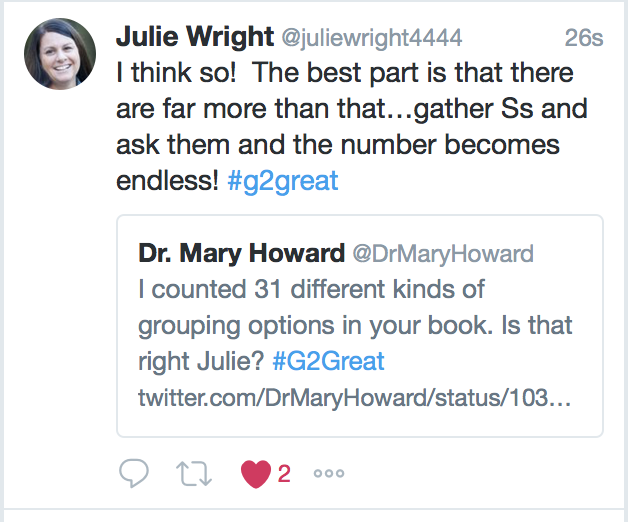

Across the pages of their wonderful book, they describe these options so vividly that teachers can pull from a treasure chest of thirty-one grouping possibilities listed at the front of the book according to the specific needs of students. But as Julie reminds us in the tweet below, that number multiplies exponentially if we can have the courage to invite the passions and interests of students to the small group decision-making table.

When I’m honored to write a #G2Great post on a book, my goal is to honor the book and author/s while drawing from the chat experience. To do this, I first look to the book for inspiration by exploring a few tidbits of wonder as I did above. Then I look to the chat for social media tidbits of wonder from our author/s to extend the book. A book/chat merger helps me mine for big picture messages. Perusing our #G2Great chat WAKE for patterns wasn’t an easy task since Barry and Julie each tweeted thirty-three brilliant ideas. While tweet awesomeness challenged my mining process, patterns began to emerge as a starting point to bring their combined book-twitter wisdom to life. To maintain my focus on these patterns, I decided to use a pair of tweets per point with more selected tweets at the end.

And so, Eight Small Group Redesign points that tapped me on my Julie-Barry inspired shoulders:

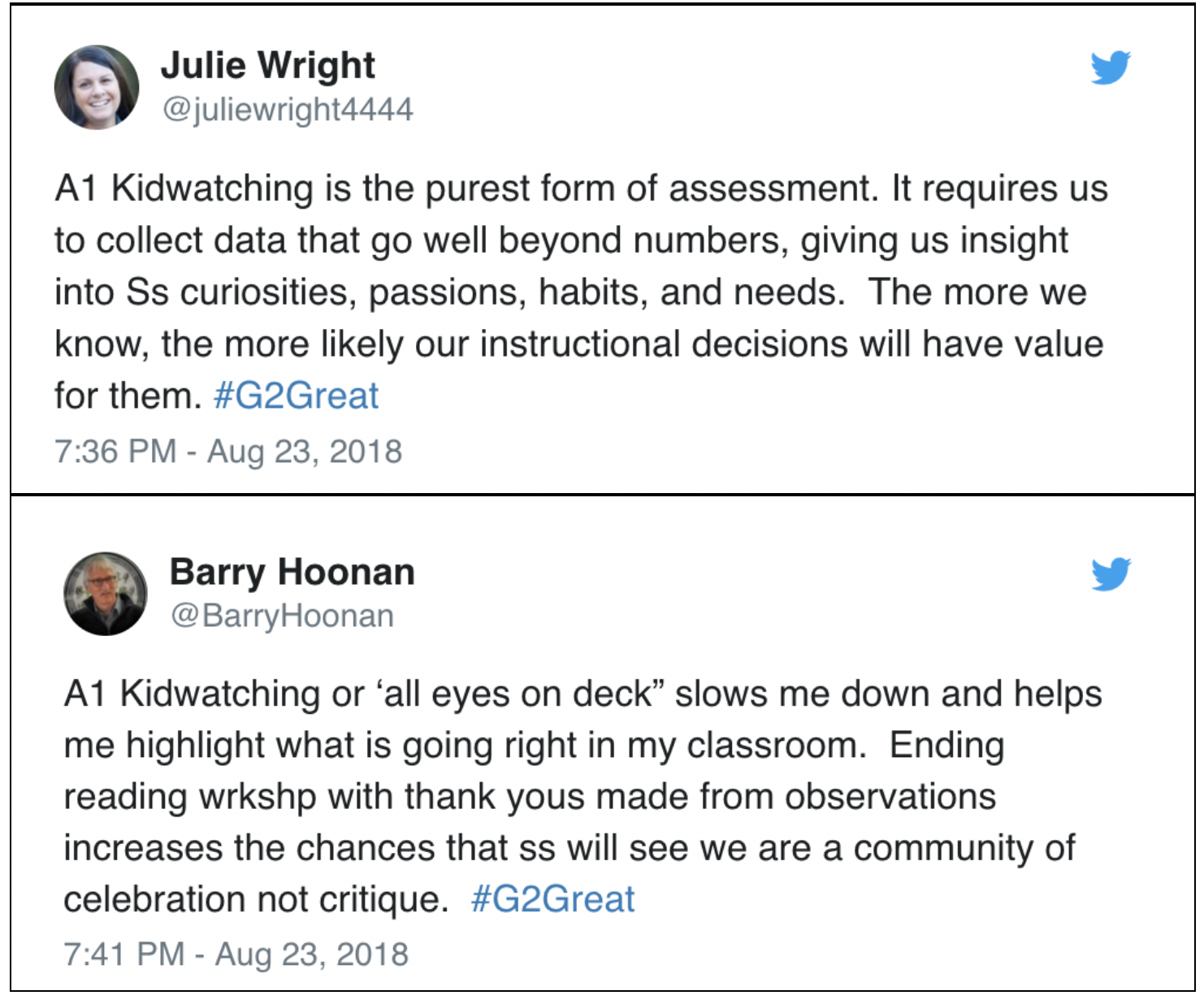

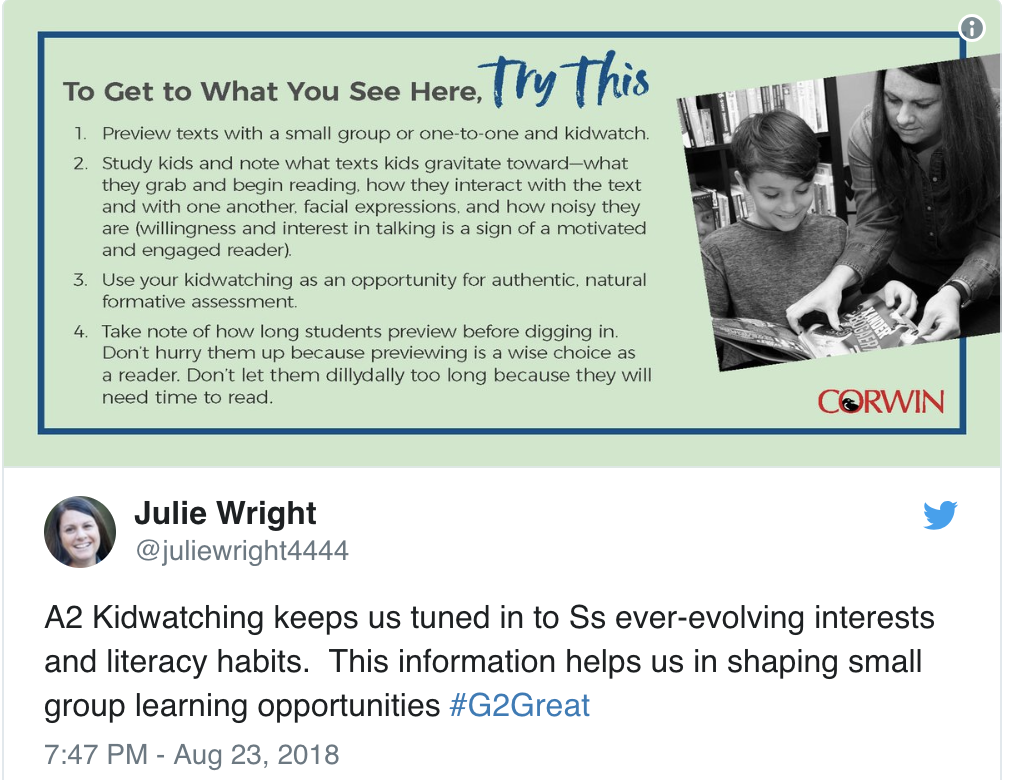

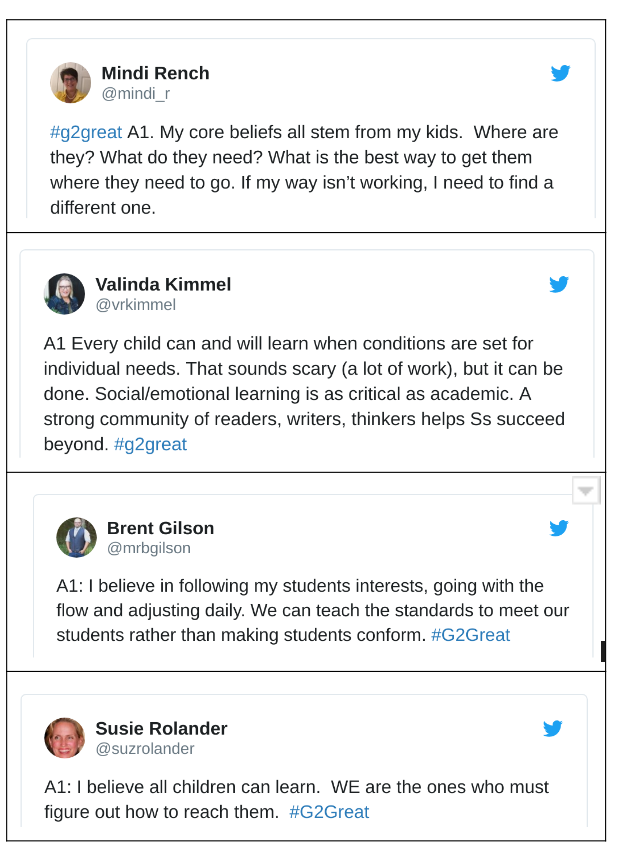

Small Group Redesign # 1: Explore Directional Signposts

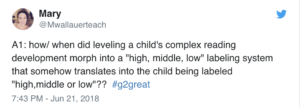

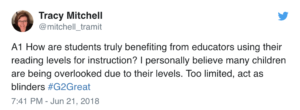

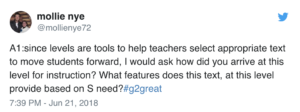

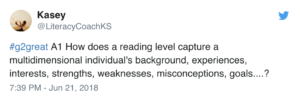

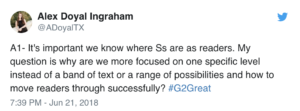

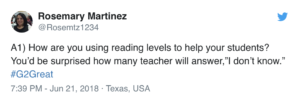

Our first question about the role of kidwatching in small groups initiated a frenzy of chat enthusiasm that exploded across the twittersphere. Kidwatching activates a directional GPS system that inspires us to breathe deeply, slow down and step back. This sense of presence makes us privy to precious in-the-moment opportunities where the engaging work children do on their own points the way to next step possibilities. Julie emphasized that noticings help us to move beyond numbers that may blur our view of students in the throes of learning. Her focus on curiosities, passions, habits and needs illustrate critical features of learning that go unnoticed without intentional looking. Barry reminds us that this is a celebration rather than a critique. I loved his “all eyes on deck” reference focused squarely on what is “right” about the teaching-learning process in this celebratory child gazing. Changing our stance from teacher to observer with a teacher-learner mindset encourages us to keep our eyes and ears open for instructional inroads that could beckon us forward.

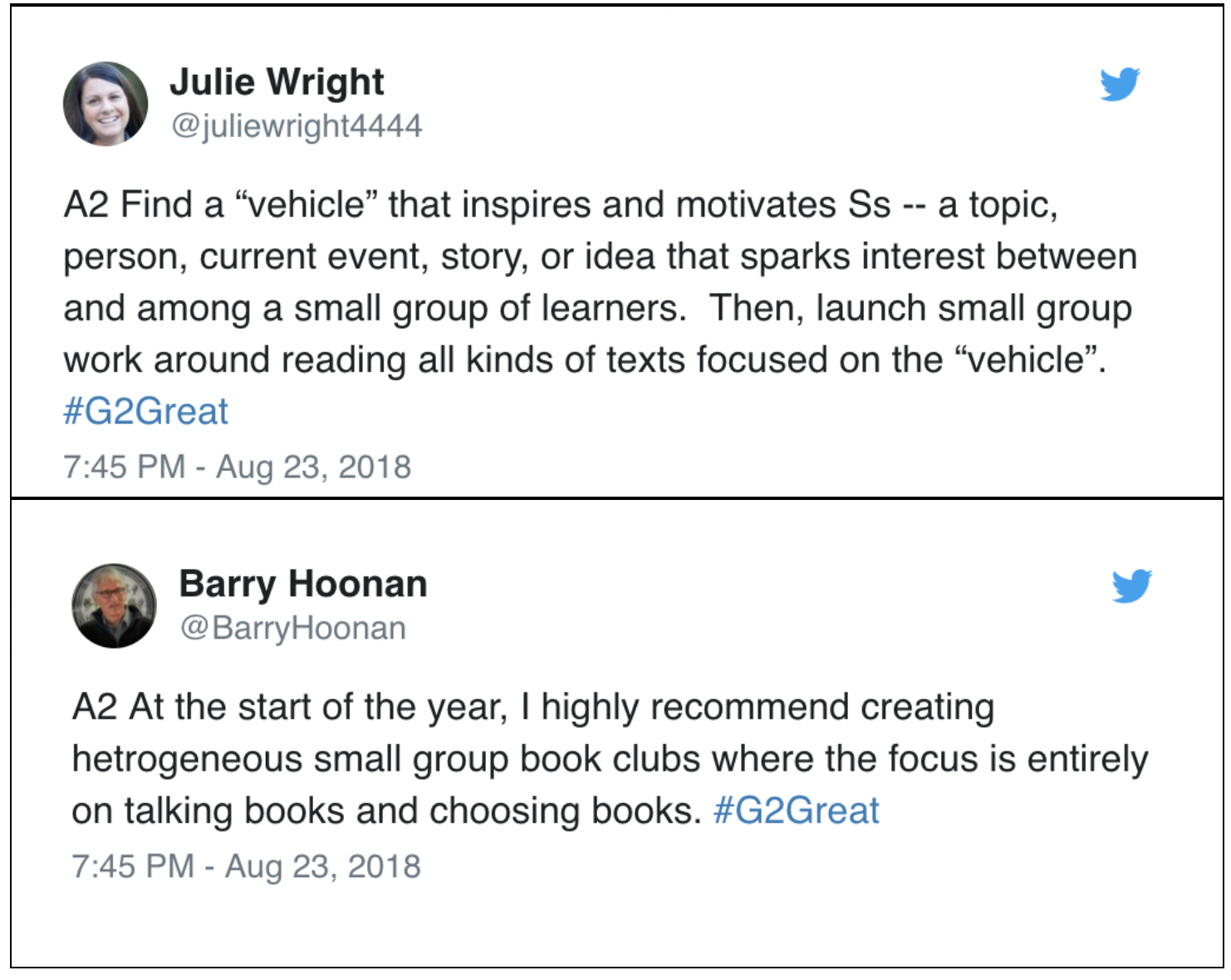

Small Group Redesign # 2: Plant Varied Small Group Seedlings

From the moment I began reading this wonderful book, I could imagine teachers inspired to plant new small groups seeds that would become beautiful blossoms across the learning year. Julie asks us to envision small groups as a vehicle for nourishing these seeds as we shift from teaching students how to read and supporting their unique journey to becoming readers. Typically, teachers are asked to create leveled small groups at the beginning of the year but Barry suggests beginning instead with heterongeous groups that will help us to get to know students as readers and set the stage for future groupings. Relinquishing teacher control initially for the purpose of understanding learners reminds me of the Roaming in the Known phase of Reading Recovery. Once we know what inspires and motivates our learners, this fuels our efforts to nurture becoming across varied settings.

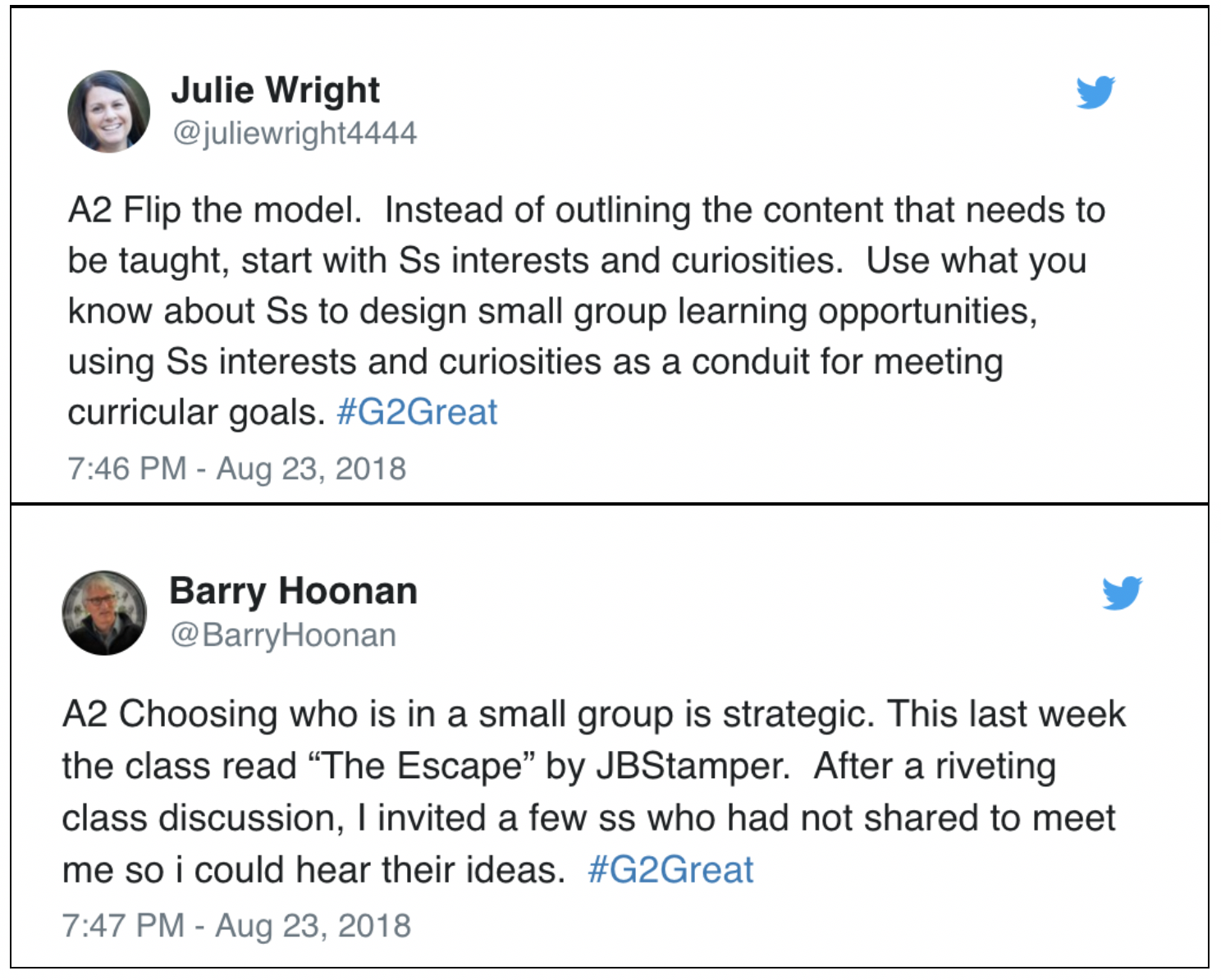

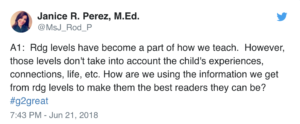

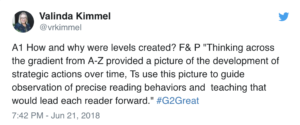

Small Group Redesign # 3: Be a Strategic Decision-Maker

When the choices that we make about small groups are made solely on isolated numbers, even if those numbers may be relevant, we may alleviate the opportunity to form groups informed by the day-to-day learning experiences that can enrich our grouping efforts both within and beyond those settings. Julie refers to strategic decision-making as “flipping” the traditional model focused on content and begin by using our students’ interests and curiosities to generate learning goals. Barry implores us to make ‘strategic choices’ based on what we are noticing within those experiences in the learning day. These opportunities could then become “invitations” for a wide range of smaller settings where we can offer a gentle nudge across contexts when we recognize a need for such opportunities. In this way, small groups become student-centered invitational experiences that widen our view what is possible.

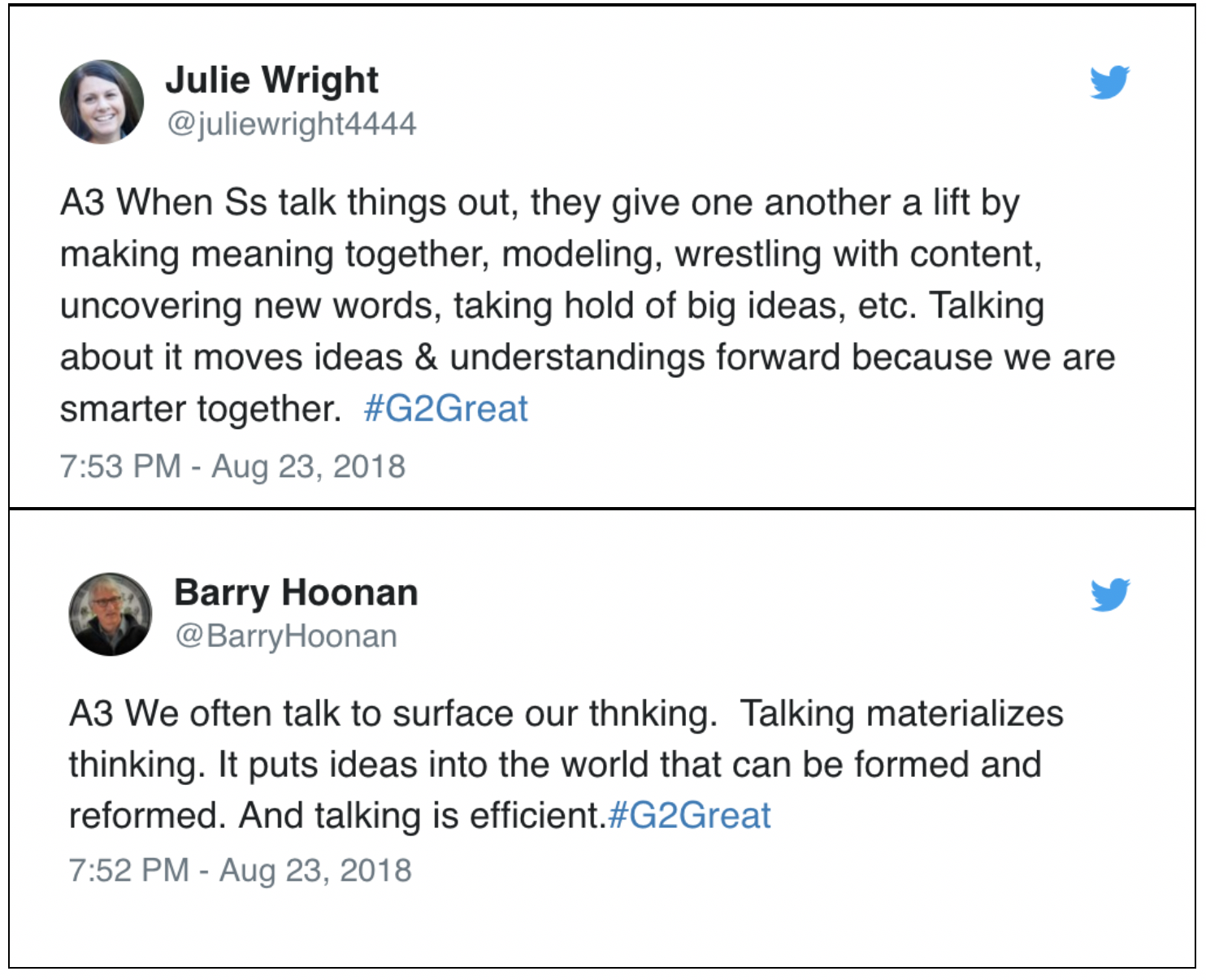

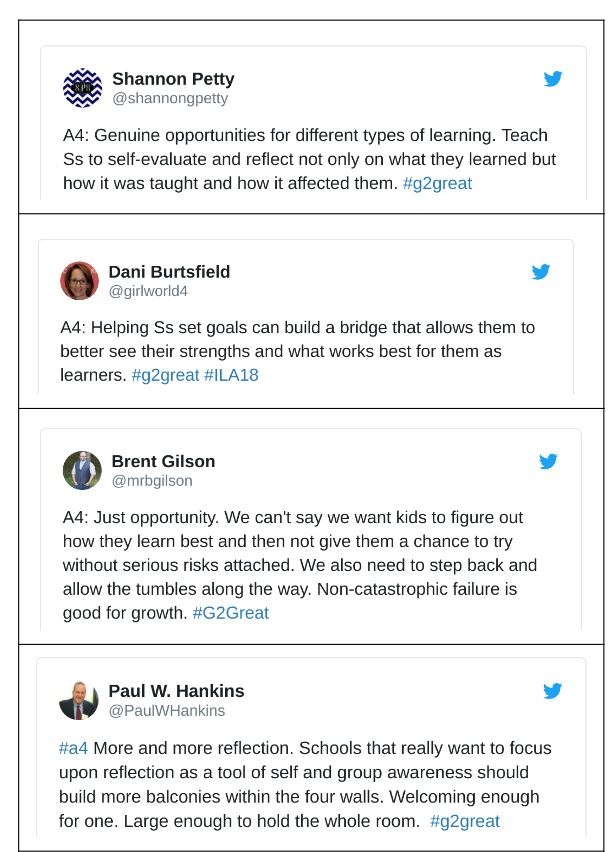

Small Group Redesign # 4: Invite Conversational Explorations

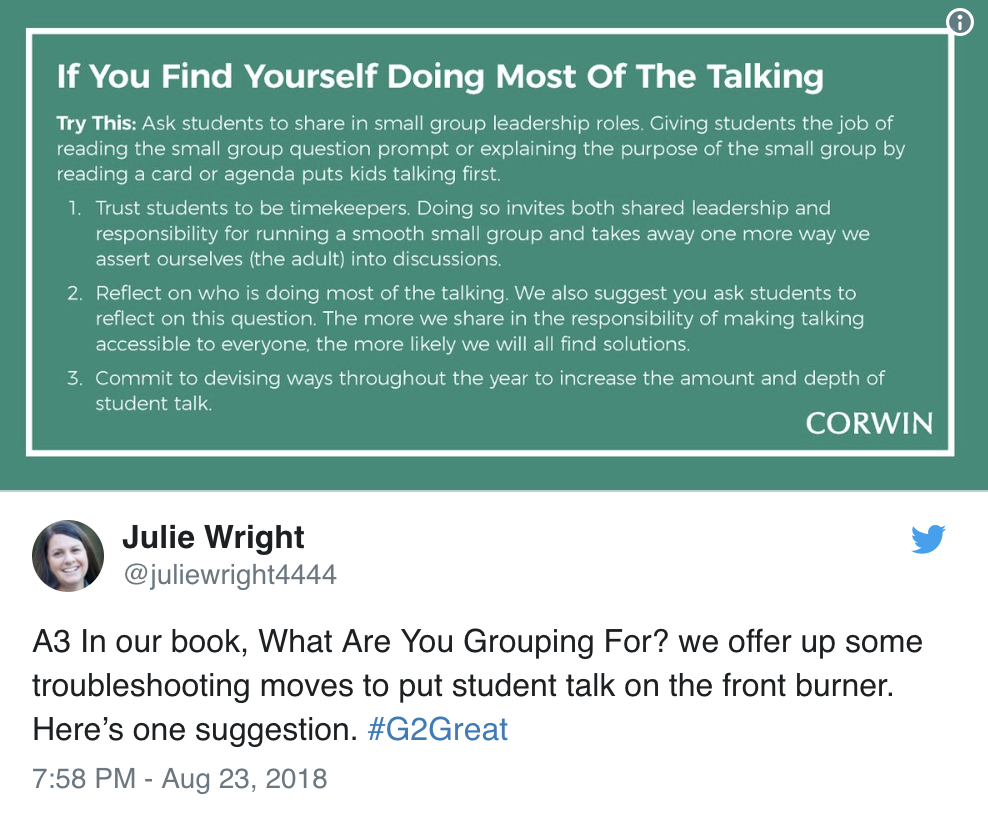

One of the hallmarks of effective grouping experiences is that students’ voices rise above our own. Yet too often the opposite seems to be the case. Julie highlights the give and take aspect of talk as a way to invite students to make sense of their thinking in the company of supportive others in a non threatening context of smaller groups. This “smarter together” stance where multiple voices can merge respectfully into one will allow us to use talk to meander our way to collective understanding. Barry asks us to use talk as a conduit that will help new thinking “materialize” through these conversations so that we can lift that thinking into the discussion air and “put new ideas into the world.” I love his point that this inspired talk is not an end zone that we seek to reach but a pathway where we can form and reform ideas in the course of inspired shared dialogue in varied settings.

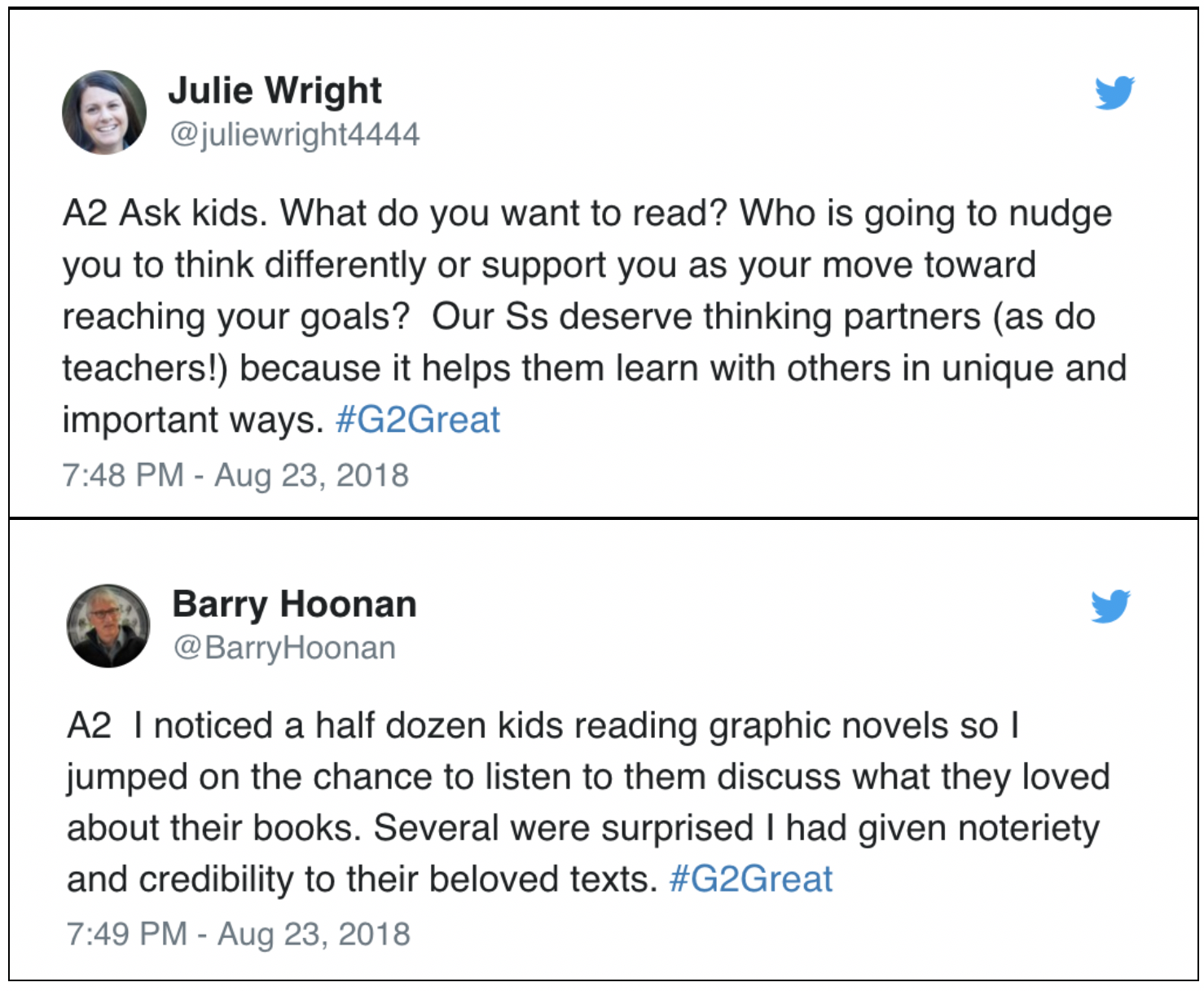

Small Group Redesign # 5: Celebrate! Celebrate! Celebrate

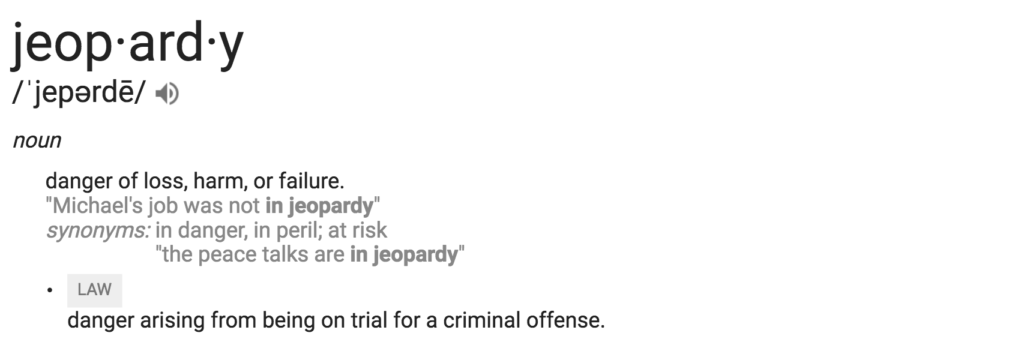

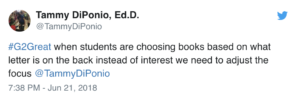

I can’t think of a more critical small group purpose than using those experiences as a way to celebrate students within and beyond the small group and as a motivation for forming new learning opportunities. Julie encourages us to ask our students about their reading choices as a gentle nudge toward using their preferences in working toward learning goals. This is essential considering we elevate goals done in the spirit of interests. She further emphasizes the value of partnerships where texts can be used as a conduit in collaborative explorations that deepen and fine-tune initial thinking. Barry highlights this celebratory spirit by acknowledging and supporting their reading identities through student driven choices. The fact that his students expressed surprise when he celebrated graphic novels as a relevant choice illustrates the potential danger when we negate certain texts as unworthy rather than leaning joyfully into them. Barry clearly leans in with gusto.

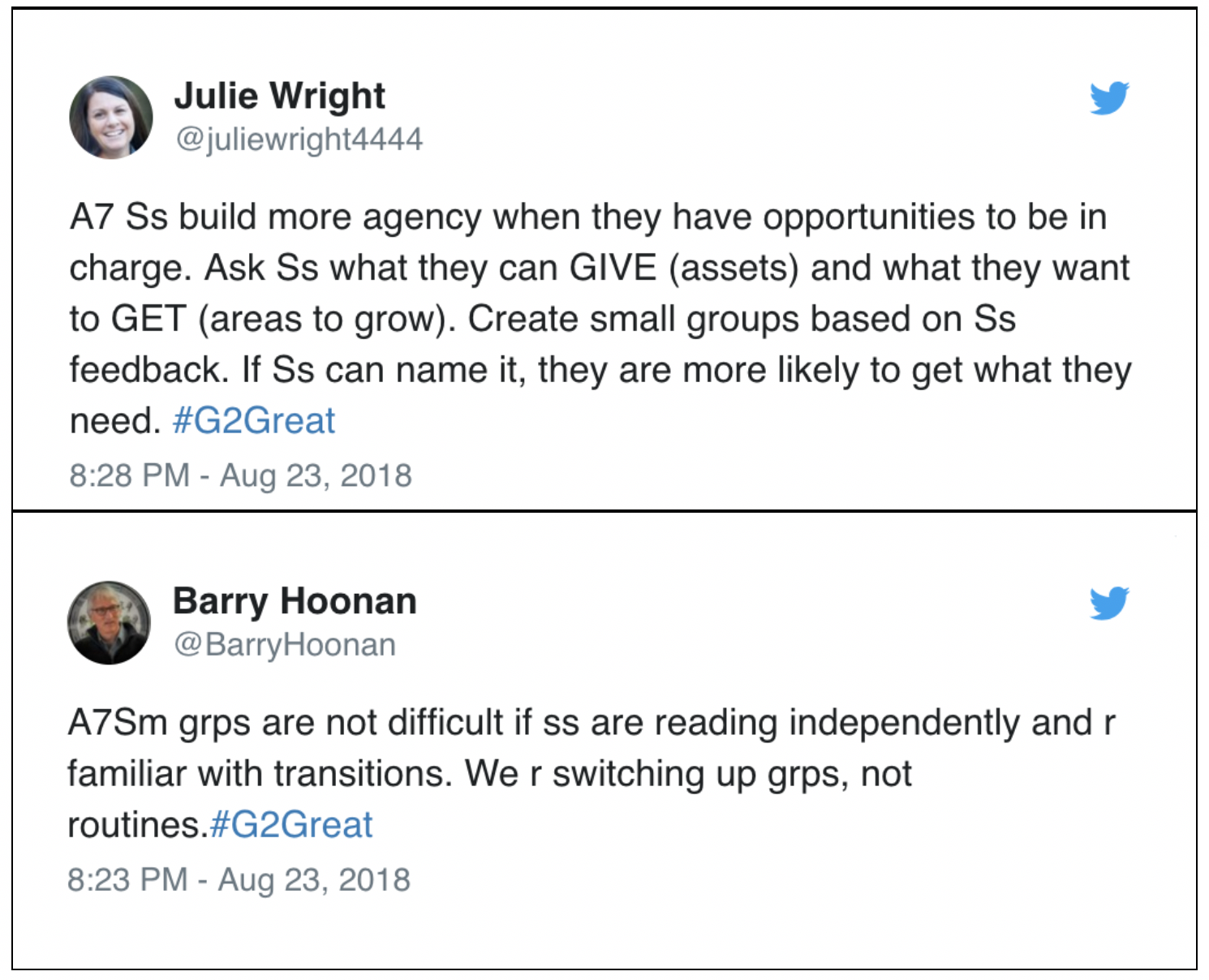

Small Group Redesign # 6: Build a Student-Centered Bridge

It would be hard to argue that student independence is the ultimate goal of small group endeavors and our student-centered bridge will support this shift in responsibility. When teachers maintain control for small group learning rather than relinquishing those reins to students, this transfer of independence from teacher to student is unlikely. As Julie so eloquently reminds, we must embrace this handover of responsibility by supporting their increasing control. We look to students for signs that point the way and then trust them as they move across a bridge leading to student agency. Barry illustrates that the rituals we put in place at the beginning of the year can help us to support and strengthen this goal across the year. We increase the likelihood of this transfer of responsibility when we put students in the small group driver’s seat as they become familiarized with routines and then have the courage to step back so that they can assume ownership of this process.

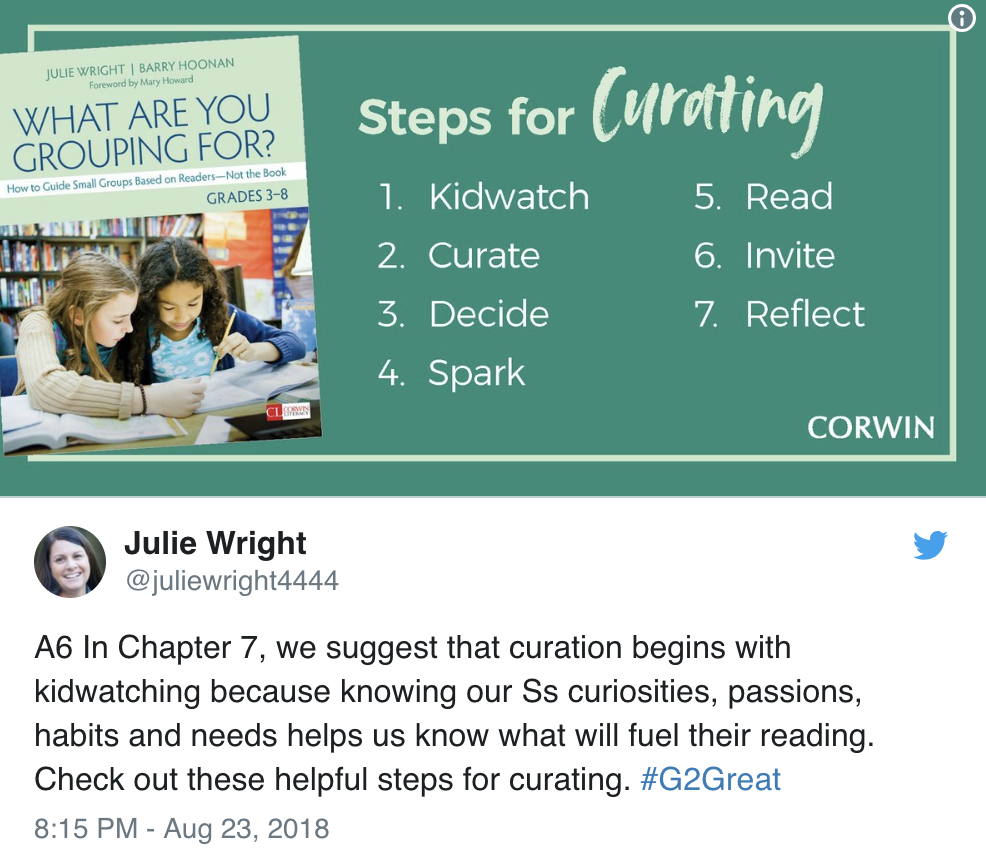

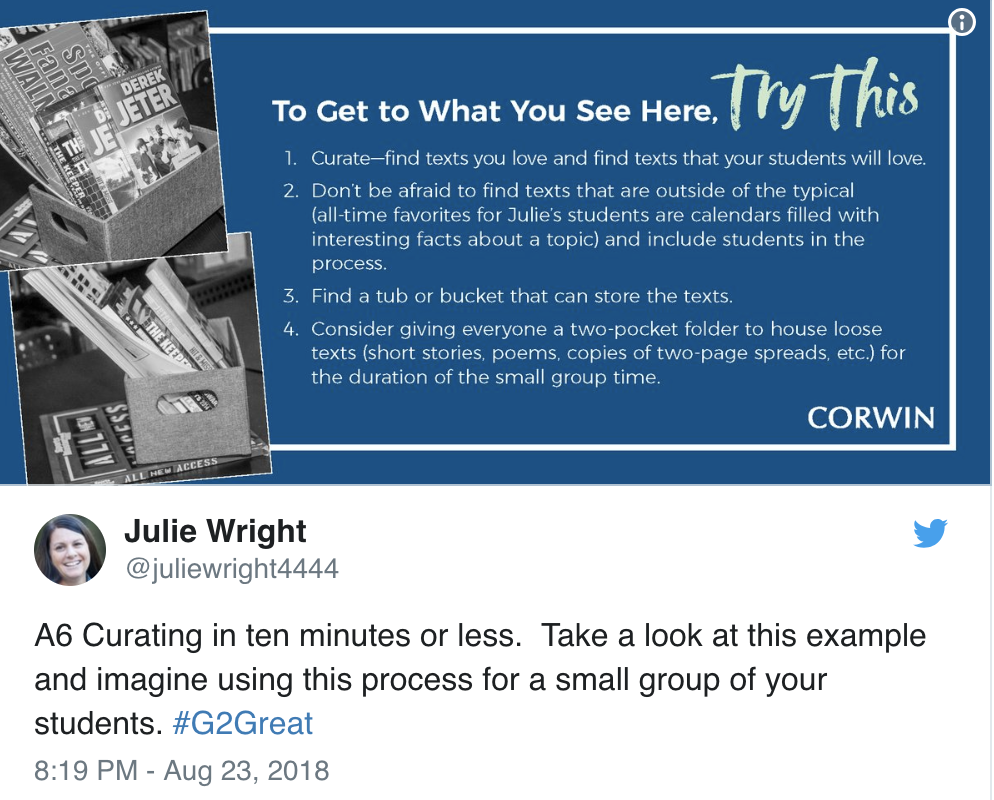

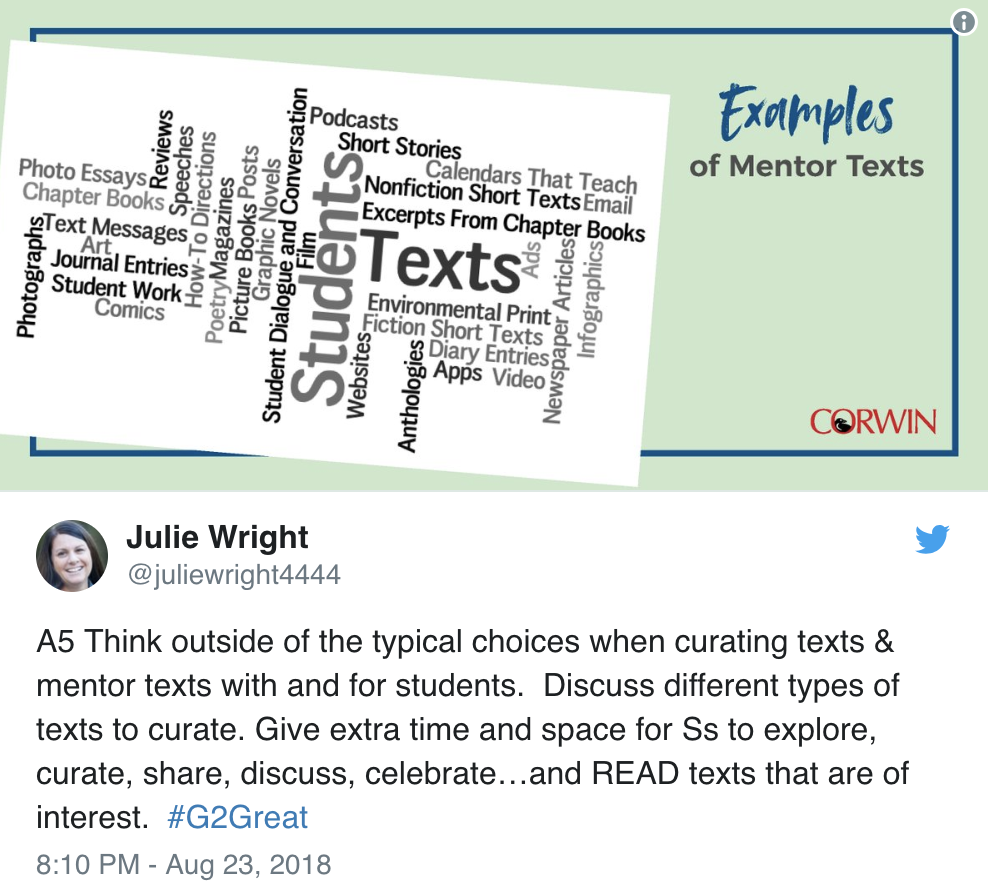

Small Group Redesign # 7: Generate a Text Treasure Trove

One of the topics that I found myself returning to again and again in the book and the chat was the idea of text curation. These text collections are a varied gathering of options for reading based on student interests used both within and beyond small group experiences. Julie reminds us that these teacher vs student curations are not an either/or proposition but that we must always strive to include students in this process. This may reflect student created displays of topics, genre, authors or learning goals coupled with advertisements to inspire new small groups, with a range range of text options welcomed. Barry emphasizes the role of texts, students and teachers in this curation process, but again asks us to keep our sights on relinquishing curation responsibility to students. When students do this gathering for themselves and their peers, those collections will represent their interests, passions and curious wonderings as they own this process. As a result, we are afforded the gift of understanding them as learners by virtue of the very collections they curate.

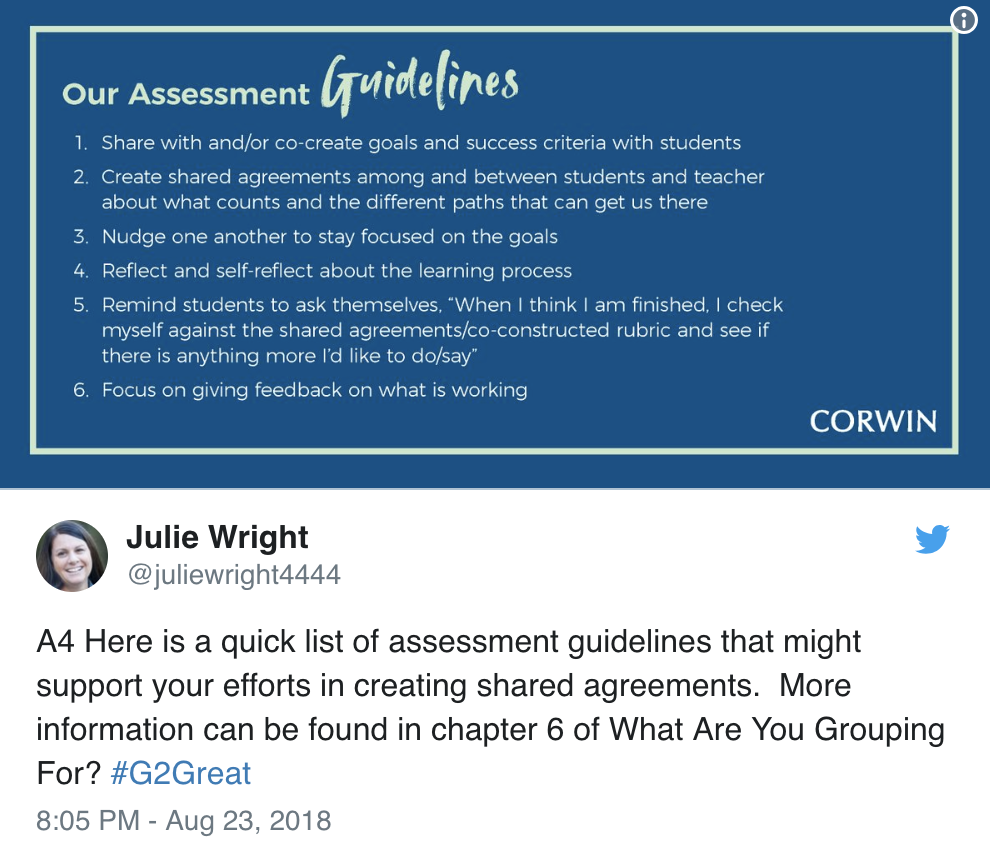

Small Group Redesign # 8: Assess/Act/Assess – Repeat

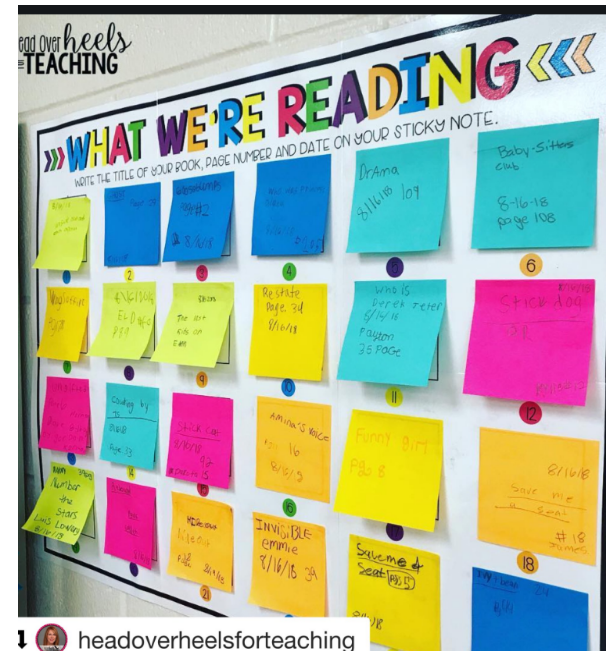

Each of these eight points work in tandem rather than in isolation and this final point in no different. Assessment is not something we do and then move on but what we do across the year as we inform, form, reform– all the while gather new assessment informants for this small group work. Julie extends this perspective by asking us to broaden our view of what assessment can look like, sound like and feel like. A wide range of multiple sources of formative data support our next step thinking by allowing us to see students from all sides. I included Barry’s reference to the use of student photographs since I see this as a powerful concrete visual assessment tool that can become a springboard to promote questions and ponderings. The back and forth discussion that can rise from this pictorial view of learning affords assessment information that might otherwise be invisible since the photo captures learning in action and the dialogue it inspires allows us to relive those experiences.

I would like to extend a very personal heartfelt thank you to Julie and Barry – not only for writing this incredible book but for trusting me to write a foreword that would do their book justice. On behalf of myself and co-moderators, Fran, Jenn and Amy, we are deeply grateful for their generous sharing of small group wisdom with our #G2Great family of enthusiastic learners. As a result, I can envision a wide repertoire of student-centered flexible small group designs that will “engage, inspire, and foster collaboration.” I know that this wonderful book will empower teachers to step out of the existing small group boxes that have existed for too long so that they could imagine what is possible when we are willing to break free of the ties that bind so that students can do the same.

As I close this post, I am drawn back to the opening of their book and the very page that made me utter an exuberant YES to writing the foreword. In the introduction, they shared student photographs and asked us to describe what we see and then added these words,

“We hope you see joy. The joy in looking across pages. The joy in reading something you find interesting. The joy in sharing texts with friends. The joy in finding a comfy spot to read.” (Page xix)

We see it my friends. We definitely see it!

More Julie-Barry Inspired Tweet Wisdom

Helpful Grouping References Shared by Julie

LINKS

Corwin Book Link: What Are You Grouping For?

Corwin webinar with Julie and Barry