Check out a record of the chat here

by: Brent Gilson

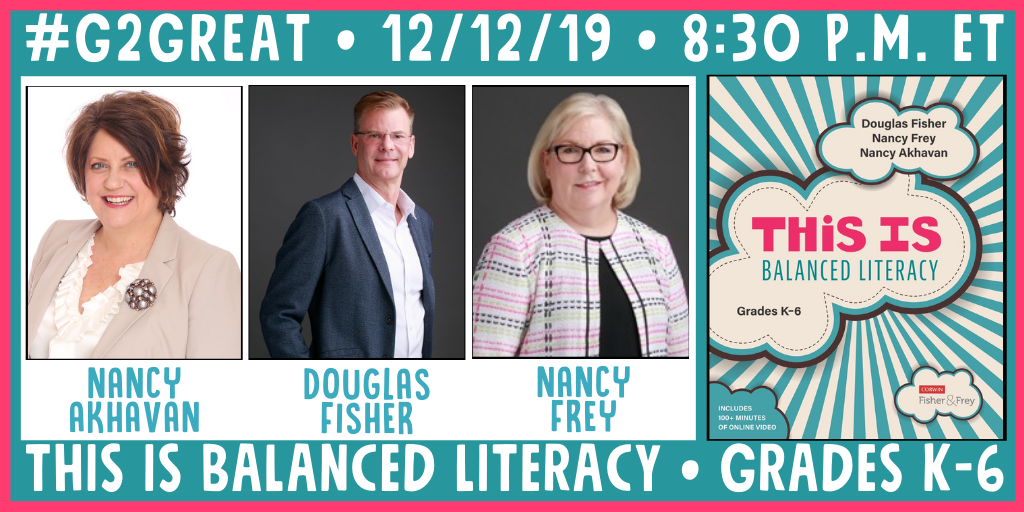

Words from the authors

1. What motivated you to write this book? What impact did you hope that it would have in the professional world?

We believe that the term “balanced literacy” has lost its meaning and we thought it was time to reclaim the term. Originally, the term was coined to ensure that there was appropriate, evidence-based teaching and learning in foundational skills and meaning-making. At the time, the “reading wars” dominated the conversation and this was an attempt to ensure that the field moved forward. Since then, some aspects of “balance” have been lost and we continue to learn about the necessary conditions for students to learn to read, write, and think at high levels. Our hope is that teachers and school systems revisit their literacy instructional models and update them with current evidence about teaching literacy.

This past week we had the fantastic opportunity to chat with Nancy Akhavan, Douglas Fisher and Nancy Frey about their new book “This is Balanced Literacy” I have a copy and it really is fantastic. In a literacy landscape that is becoming increasingly bumpy as some try to misrepresent the definition work of balanced literacy and so many other terms, we need more texts like this to serve as a tether to the real work we are doing.

I graduated from University in 2010 and in my introduction to Language Arts instruction class I remember discussing the importance of a balanced literacy language arts class. When I started my first teaching assignment I walked into a very traditional classroom that I would share part-time with a veteran teacher in the last year of her career. I learned a lot from her. One thing was that there had to be better ways to engage my students, all of my students, in quality literacy instruction that met their individual needs.

I started looking into different texts and at the time settled on The Daily 5 by Gail Boushey and Joan Moser. As I learned to structure my classroom in a way that provided my students with opportunities to explore reading and writing both independently and in groups as well as work with them in small groups and one on one I realized what had been missing.

Balanced literacy structures made room for my students to get what they needed from me, in whatever amount that turned out to be, and then explore who they were as readers and writers. It was never a free for all, it was not the wild west of literacy instruction. It was structured, we worked on skills when I taught third grade we had targetted time for those striving readers working on phonics in guided reading lessons while the majority of my class worked in other stations. What sold me on it the most was that even those kids who did still need those foundational skills had opportunities for independent exploration to discover their reading and writing selves.

Words from the Authors

2. What are your BIG takeaways from your book that you hope teachers will embrace in their teaching practices?

A few things come to mind. First, learning to read is hard. Every brain must be taught to read. We do not pass down a “reading gene” from one generation to the next. Intentional and targeted instruction is essential to accomplish this. Second, there is evidence for both direct and more dialogic forms of instruction. Both work if they are used correctly and for the right aspects of literacy development. It’s not an either/or, it’s a both/and. As a profession, we are still learning a lot about the ways in which talk mediates learning. Third, the role of practice is widely misunderstood. To learn well, students need distributed, deliberate practice. Planning and monitoring practice is important and something we all need to learn more about. Fourth, students need to be involved in literacy through the gradual release of responsibility. They can start at any point in the gradual release model as the collaborate, practice, work with the teacher or receive direct instruction from the teacher. Balanced teaching is about incorporating all four parts of the gradual release into our students’ literacy experiences.

As the chat took off on Thursday there was so much to just take in.

As Nancy and so many mentioned in their responses to the first question balanced literacy includes so many wonderful aspects of both reading and writing. We are not putting limits on our students. We are guiding them, lifting them up and assisting them in both their skills and passion for literacy work. As I considered this first question the idea of the opportunity to promote equity came to mind.

I am teaching junior high now and at times the shorter class periods and structure challenges get in the way of the traditional balanced literacy approach I use to have in elementary. Reflecting on how much easier differentiation was, how much easier it was to address individual student needs in a well organized balanced literacy classroom has me back to the drawing board as I reorganize to make the structure work.

So often we see from voices that oppose balanced literacy or have created their own definition of what it is the notion that it is not a place for direct instruction. If we are judging by the chat this is simply not true. Countless teachers agree that direct instruction has a much-needed place but it is the amount of time spent that tends to be a point of difference.

Balanced Literacy structured class provide the opportunity for students to read, write and share but also provides us with multiple different teaching opportunities like whole class, small group and individual. I see a lot on Twitter the idea that “all kids need” and while I agree there are a few things all kids need I love the opportunities that become available when we have a structure that allows us to look at what each kid needs specifically. Small group and individual instruction give us the opportunity to do more. Instead of being guided by what we think they all need we can assess them and plan how best to address those areas where growth is needed.

I am so incredibly grateful for the community that #G2Great is. I intend on spending some time with this book over the holiday break among a stack of others. Our work is hard. With a constantly changing world of education and different practices being pushed from one voice or another I feel two things remain true. Looking to the authors’ final response we find the first truth,

Words from the Authors

3. What is a message from the heart you would like for every teacher to keep in mind?

You did not pick the easiest profession, but you did pick one that will have a significant and lasting impact on the lives of others. Learn everything that you can so that you can meet the needs of those students lucky enough to call you ‘teacher.

The second point is that in the end all of this work is, for one thing, the kids. No one child is the same as another and so it only makes sense that our instruction is not one size fits all. As this chat has so beautifully reminded us we need to be purposeful in our decision making, guide our practice with formative assessments and create a learning space where all students have access to what they need. A Balanced Literacy Classroom provides this opportunity.