This week, #G2Great addressed a topic that is at the very heart of thoughtful professional decision-making. On 11/1/18, your #G2Great co-moderators enthusiastically reflected on building a literacy base as we posed the question: How Do You Define Literacy Expertise, Experts, and Research? It was clear from the first tweet that our dedicated family of learners had strong feelings about this question and were eager to explore their thinking in the company of others.

Early in the chat we asked our friends to tell us who they depend on to inform their practices. It wasn’t surprising to see that the list of trusted researchers and authors who inspire them quickly grew:

Richard Allington; Donald Graves; Don Murray; Peter Johnston; Marie Clay; John Hattie; P David Pearson; Lucy Calkins; Tom Newkirk; Taffy Rafael; Nell Duke; Ken and Yetta Goodman; Louise Rosenblatt; Kylene Beers; Bob Probst; Carol Lyons; Ellin Keene; Donalyn Miller; Kathy Collins; Fountas and Pinnell; Stephen Krashen; Stephanie Harvey; Regie Routman; Debbie Miller; Jennifer Serravallo; Gravity Goldberg; Kate Roberts; Maggie Roberts; Ralph Fletcher; Nancie Atwell; Penny Kittle; Kelly Gallagher; Kara Pranikoff; Dave Stuart Jr.; Cornelius Minor; Katie Wood Ray; Anne Goudvis; Georgia Heard; Jan Burkins; Kim Yaris; Susan Zimmerman

After perusing the tweets of this wonderfully inspired chat, I found myself lost in so many thoughts about the direction I wanted this blog post to take. These are trying times and I couldn’t shake the sense of uncertainly that amplified the magnitude of this topic. Ultimately, I decided to share my own reflections this week and then add some selected #G2Great tweets at the end of the post.

Our committed quest for literacy expertise, experts, and research has long inspired informed professionals who are dedicated to excellence. That is, however, particularly challenging at a time in our educational history when we find that we must cautiously maneuver our way through a confusing maze of good, bad and ugly. This winding path leads us to amazing research and brilliant minds but it is also sadly intermingled with less than trustworthy quasi-research and self-proclaimed experts who seem unfettered by sharing narrow opinions without the benefit of experience to back it up. As professionals, these contradictions force us to traverse the twists and turns of jumbled chaos so that we can emerge with the research and experts we know that can be trusted to give us the most principled information.

Any conversations that we have about using research to support our practices must include a discussion of our professional responsibility to read that research with a critical eye. In her recent post, Reading Research, Fran McVeigh, set the tone for this chat by illustrating the importance of using reliable research to inform rather than dictate our choices. An early chat quote from Nell Duke acknowledged this point by emphasizing our role in the thoughtful use of research. Nell Duke’s remarkable collaboration with Nicole Martin, 10 Things Every Literacy Educator Should Know about Research, reminds us of the potential dangers that research raises for “misrepresentation and misuse” and offers the purpose, role and function of research used by ‘informed educators.”

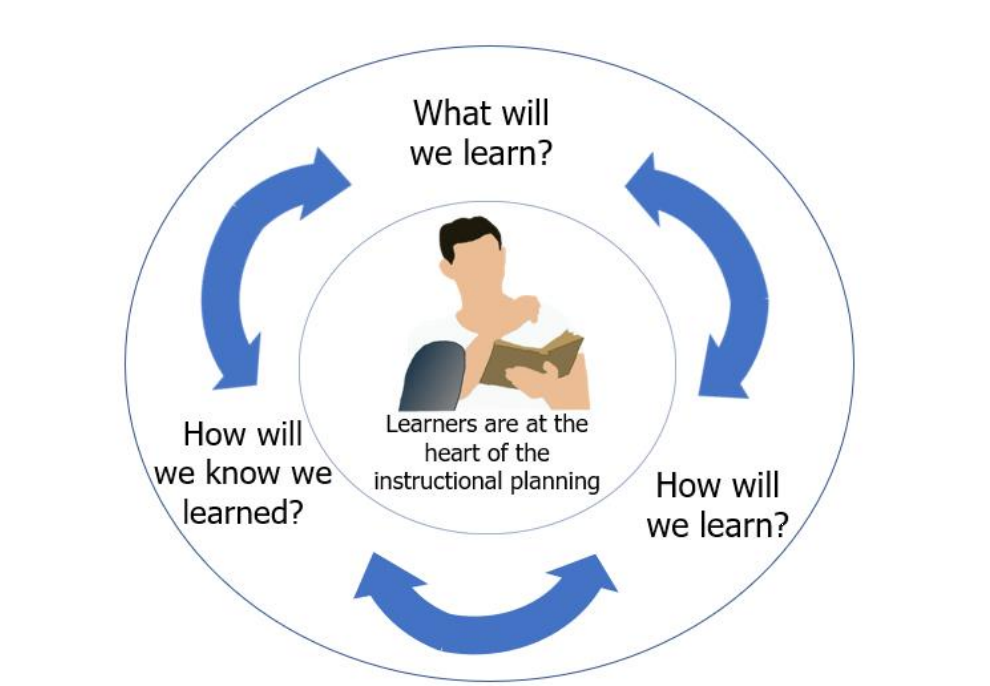

As we consider literacy expertise, experts, and research, it is important to understand that these do not work in isolation but rather are inseparably intertwined. Our committed desire to grow our own literacy expertise inspires us to pose curious queries. These queries lead us to the experts and research that continuously adds to our knowledge base and fuels more queries. Our increasing knowledge motivates us to ensure that these sources are dependable while we are aware that a single source is inadequate. We then seek the professional books and references that fine-tune our thinking and support our research-fueled understandings. Through these explorations we can then consider how this knowledge informs our current and future practices. Ours beliefs drive this process but we refine those beliefs based on our increasing knowledge. This intricate interweaving of experts and research that grows our literacy expertise allows us to bring that research to life where it matters most – in the company of children.

This inspired process of thoughtful exploration is critical given the internet and social media flood of conflicting information. While having unlimited resources at our virtual fingertips can be helpful, it can also make it challenging to weed through the sea of options that include both reputable and highly suspect references. This requires us to be responsible professionals who consistently question whether these offerings are solidly grounded on the best research. We remain must acutely aware of the dangers that can come from our refusal to question individuals, publishers and groups who happily cite research for less than admirable reasons:

Citing research to sell products

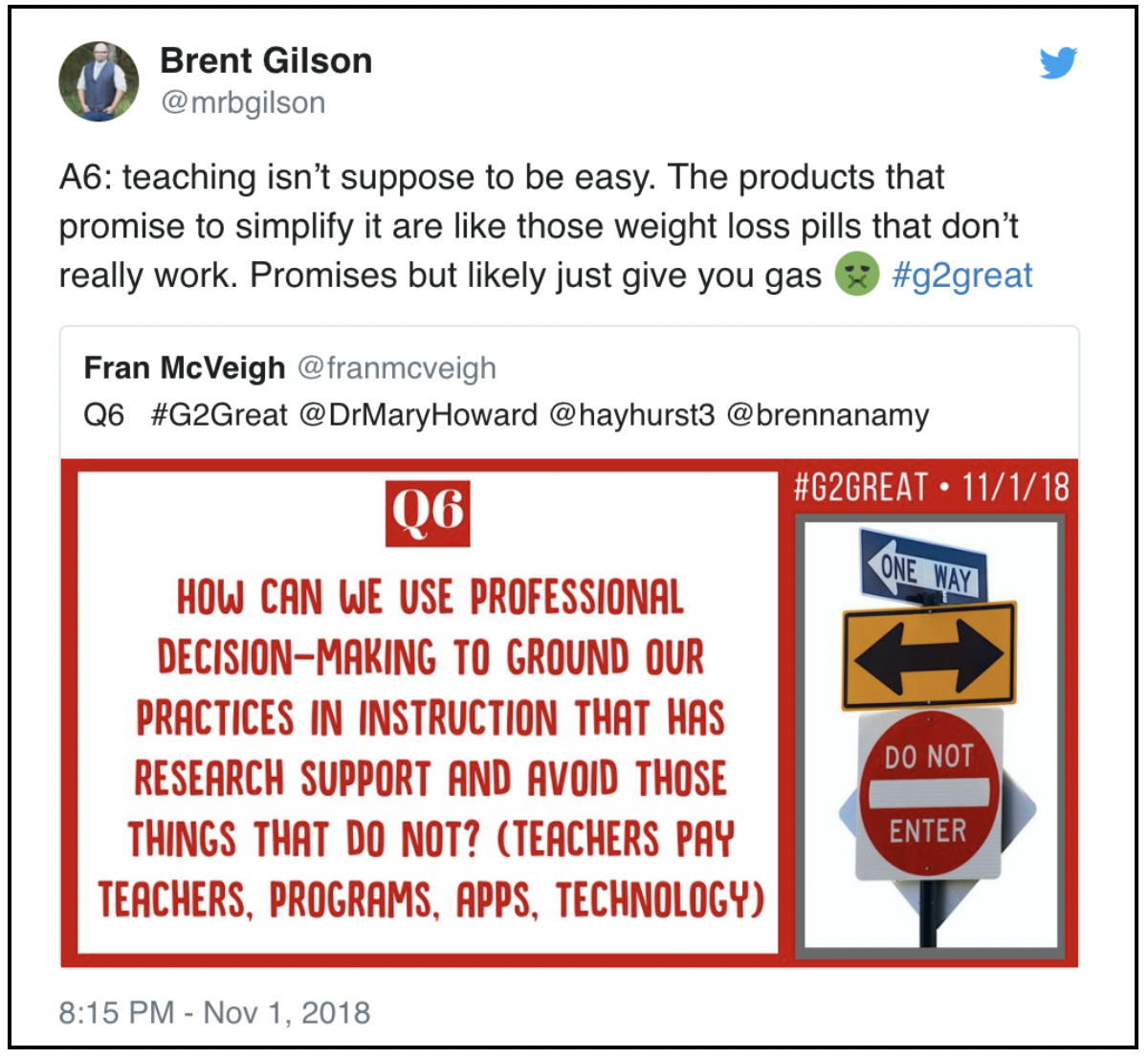

This is a common issue in an age where savvy marketeers are lurking in every corner since the internet has turned educational advertising into an instant sales pitch. This makes it common for high quality research to be cited solely for the purpose of selling a product which often doesn’t even reflect the intent of that research in the first place.

Citing research to justify practices

Social media has invited a plethora of questionable practices touted as research based. The grab and go convenience of sites such as Teachers Pay Teachers appeal to busy educators but adds a slippery slope where teachers can be sucked into time-wasting, convoluted, heavy on cute but light on substance lesson ideas and activities devoid of authentic research basis.

Citing questionable research to support an agenda

Growing groups who are currently shouting “science of reading” are building momentum, slinging verbal attacks at anyone who does not adhere to their beliefs. Nothing seems to be immune to their furor including many of our most respected experts, programs with a strong research basis such as Reading Recovery as well as universities, districts and even states across the country. The legal implications that have resulted make it even more important for us to be hyper vigilent.

Citing flawed and outdated research

In spite of the widespread failure of NCLB, Reading First and other “research-based” educational embarrassments, research rising from these efforts continues to be used with reckless abandon. While the intent seems to be to justify those practices and approaches it actually serves to confuse educators and perpetuate our educational missteps. Our educational history is littered with such mistakes and so we must acknowledge that not everything in our past is worthy of our support.

So where do we even begin when research sound-bytes of half-truths seem to cross our paths at every turn. Unquestionably, we start by making our own professional reading a high priority including books and references that are readily available and the research references. These references then afford us the opportunities to seek out the actual research so that we can read it for ourselves with a discerning and thoughtful lens. Yes, the dangers of research abound and there will always be those eager to toss research citings recklessly around for their own shallow purposes. But the only antidote that we have to fight this warped view of research is our own growing knowledge and our commitment to speaking up against those who use it for the wrong reasons.

And so in closing, our title, Building Your Literacy Base: How Do You Define Literacy Expertise, Experts, and Research?, holds the answer to where we begin since they work in combination. The very act of building our literacy base will help us to grow our literacy expertise through the experts, and research that support and extend that literacy expertise. This process is likely launch a powerful domino effect of a life-long love of professional growth that informs our practices in a never-ending quest for excellence.

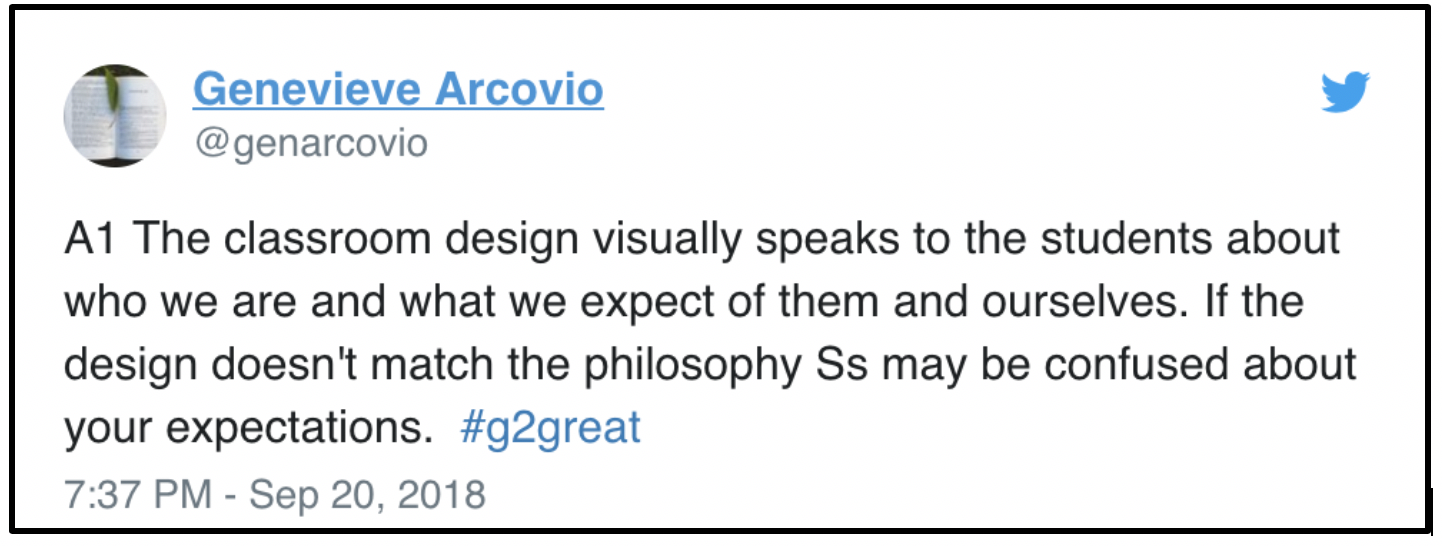

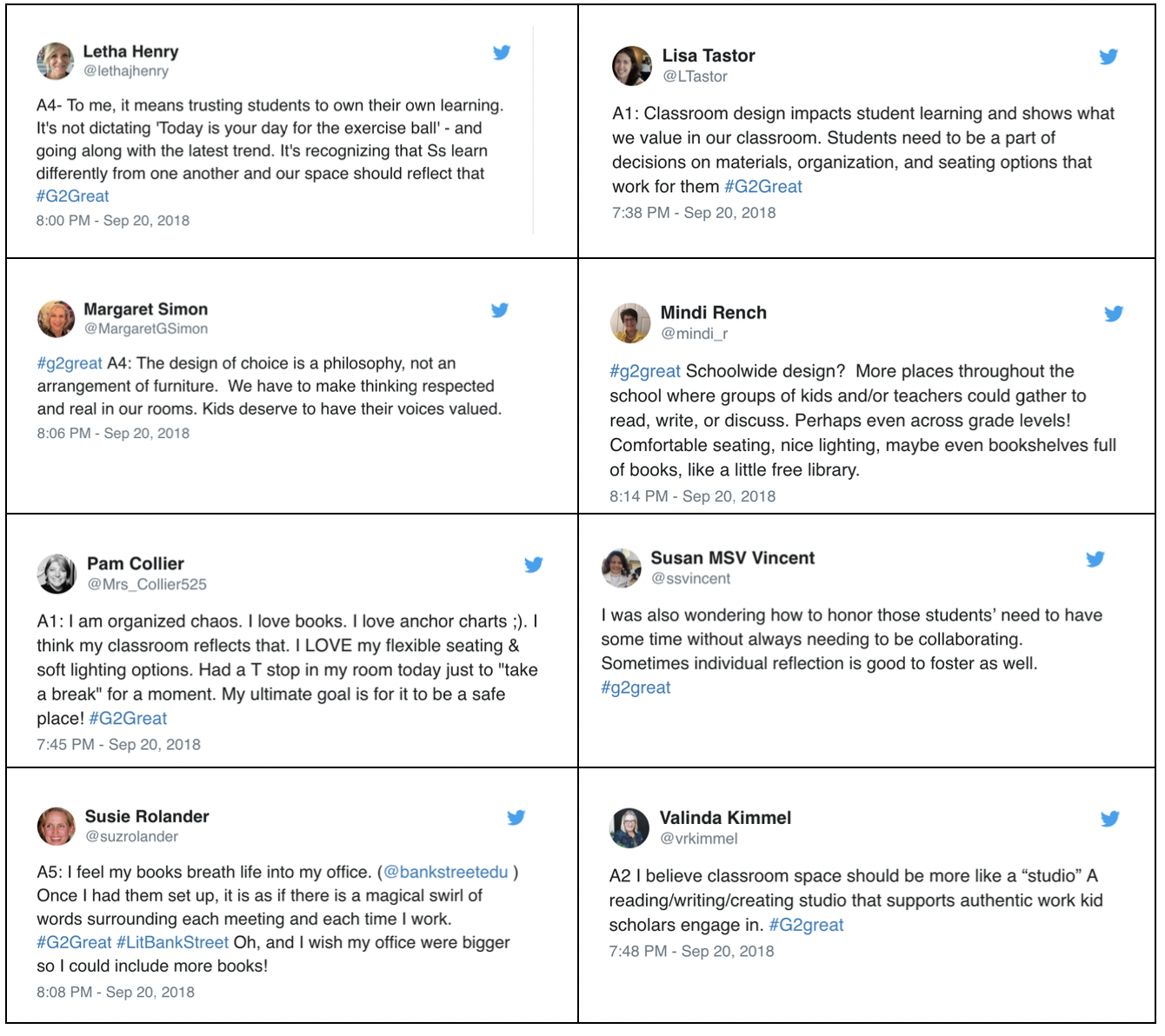

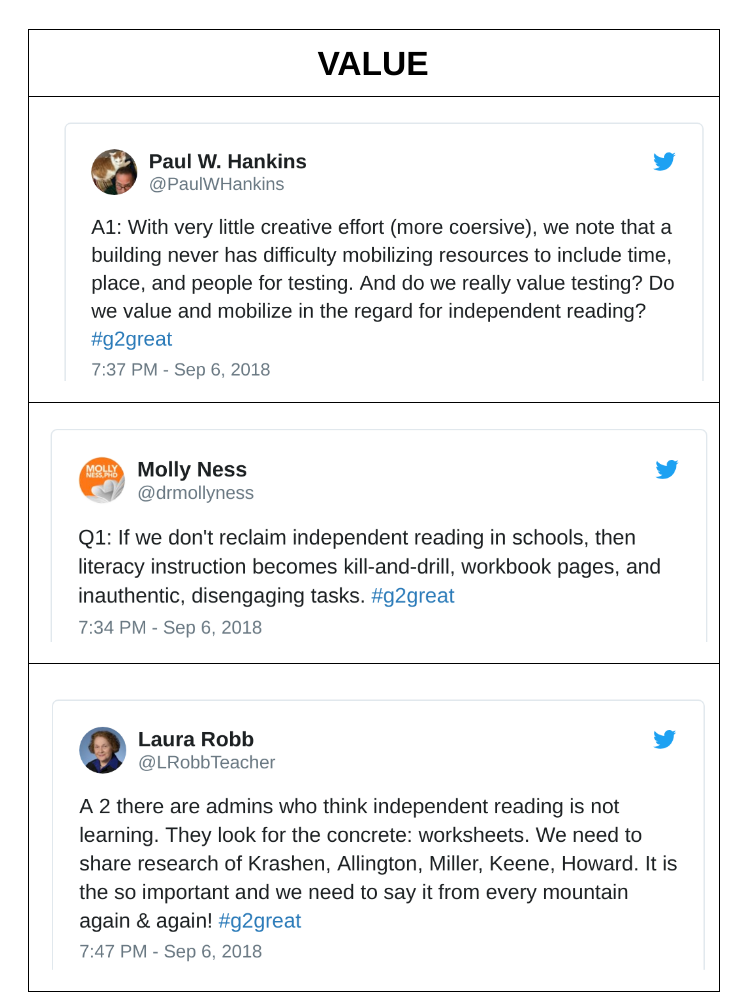

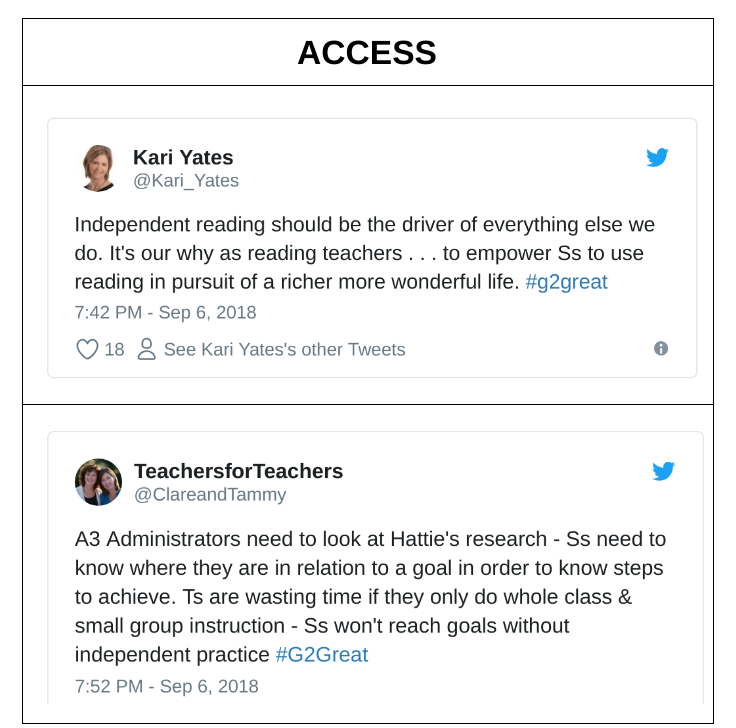

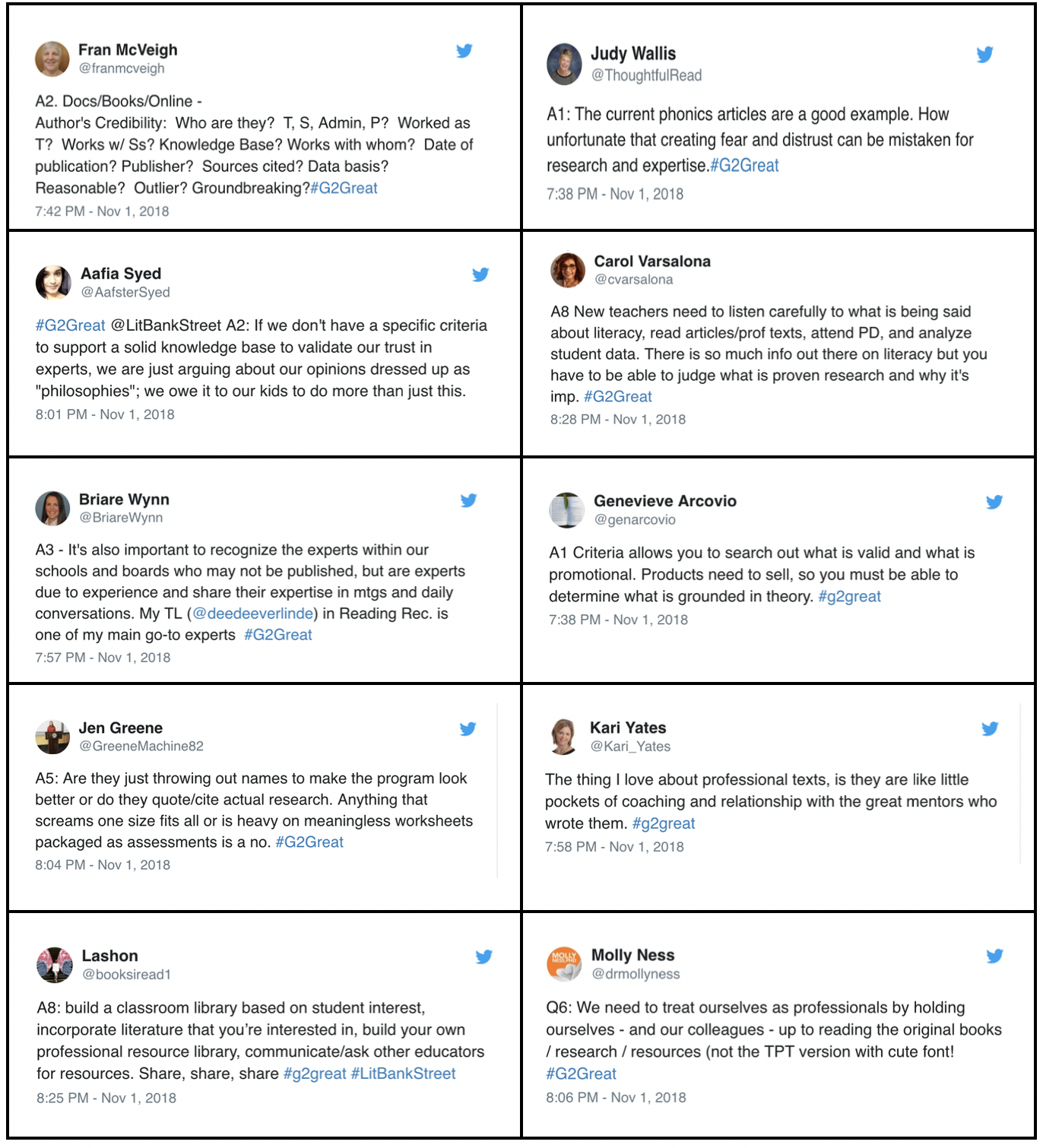

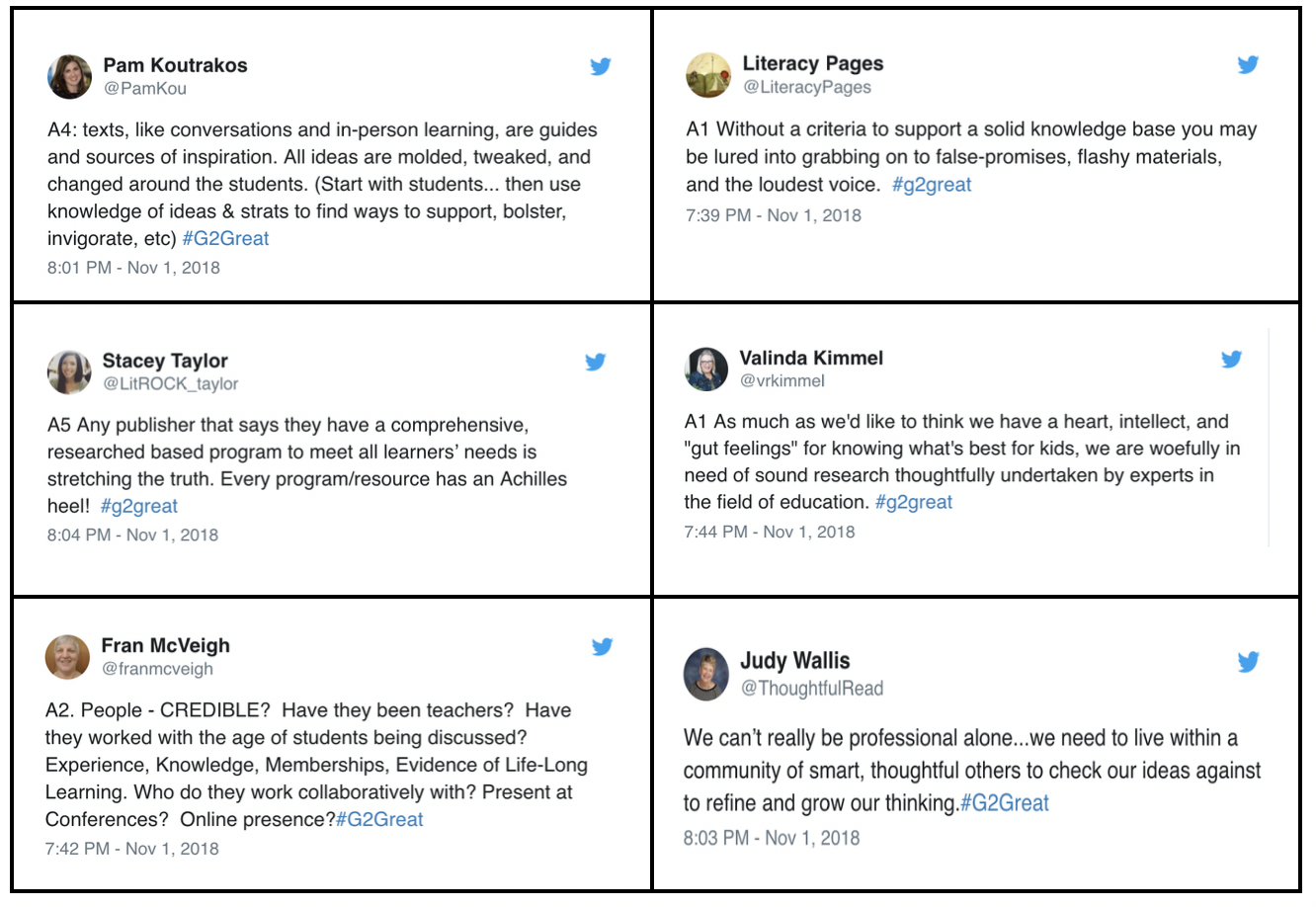

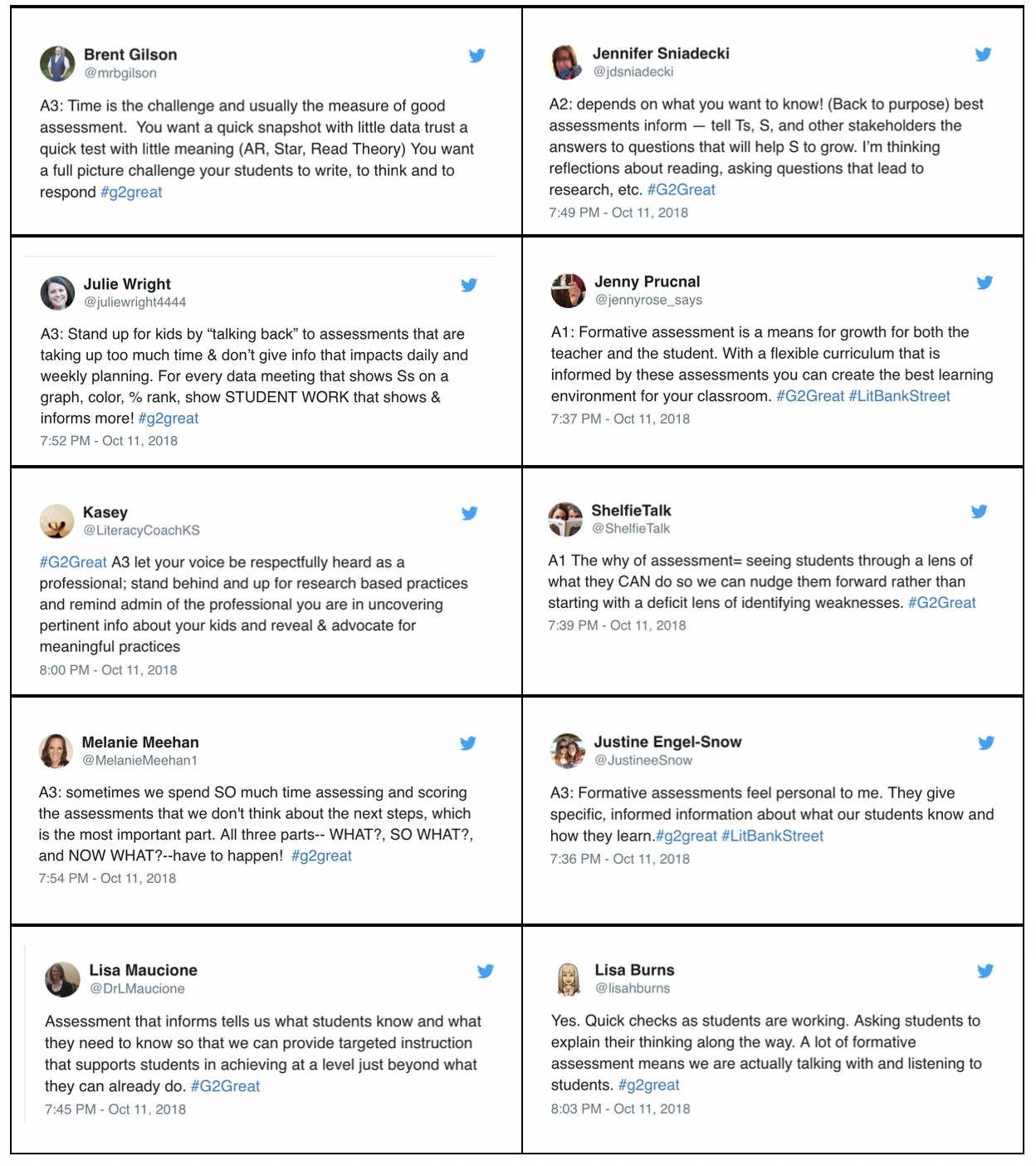

Some #G2great tweets that inspired this post

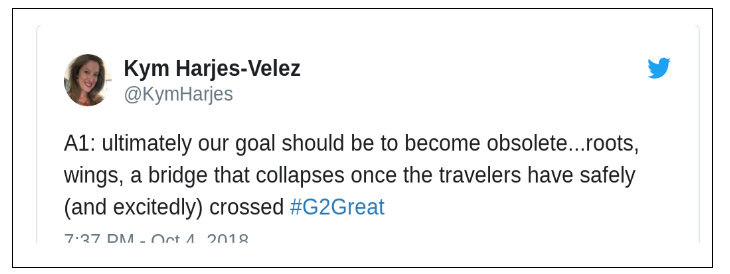

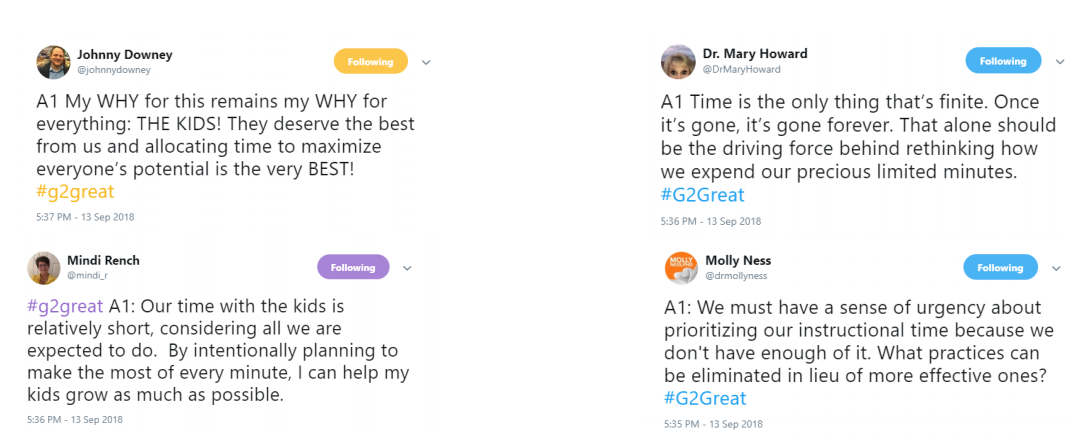

This was our opening quote. I’m going to invite you to take about 30 seconds now to pause and reflect. Pauses will be inserted at several points for some brief processing time. Pauses like speed bumps. Slow down, pause and think.

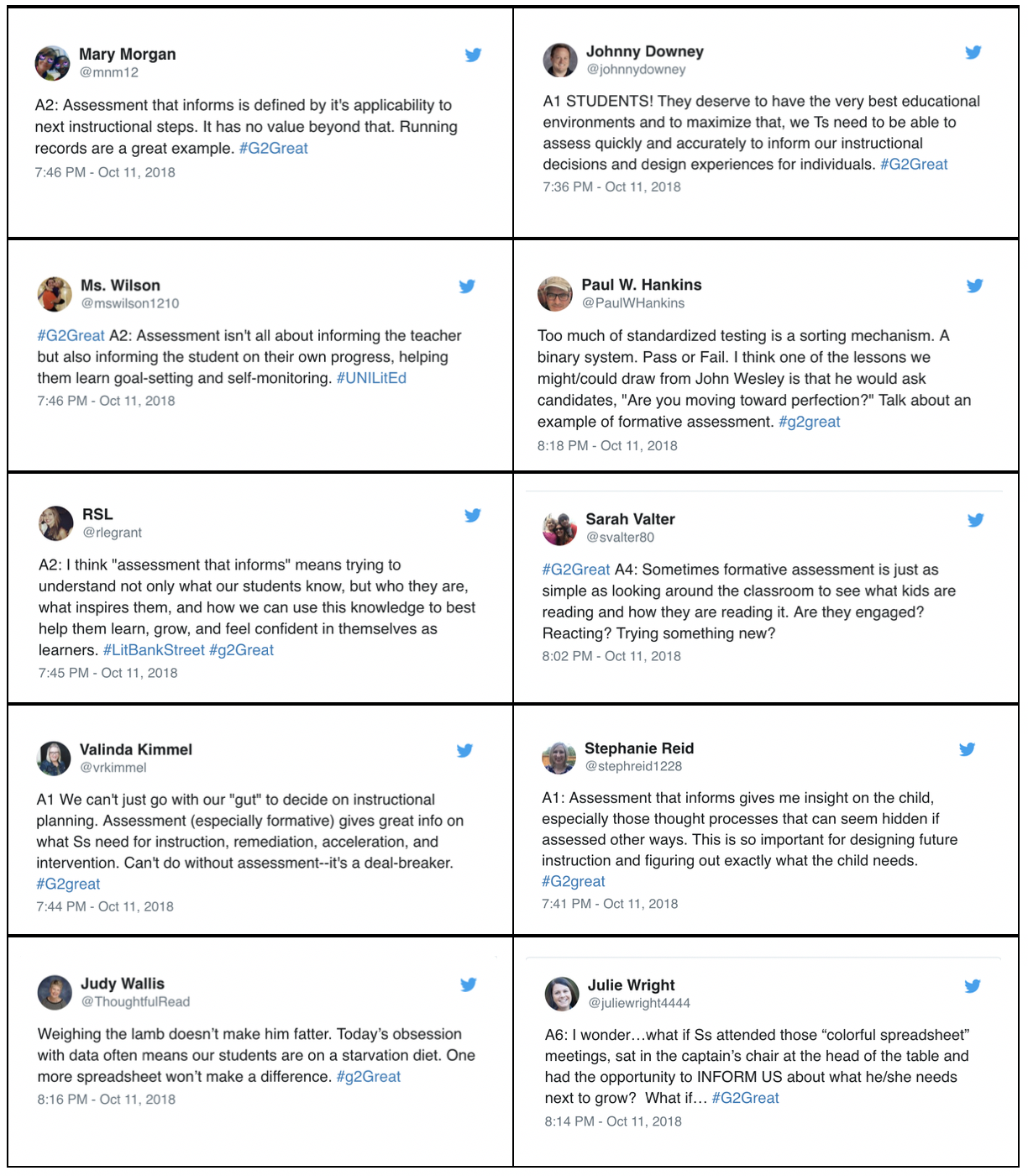

This was our opening quote. I’m going to invite you to take about 30 seconds now to pause and reflect. Pauses will be inserted at several points for some brief processing time. Pauses like speed bumps. Slow down, pause and think.

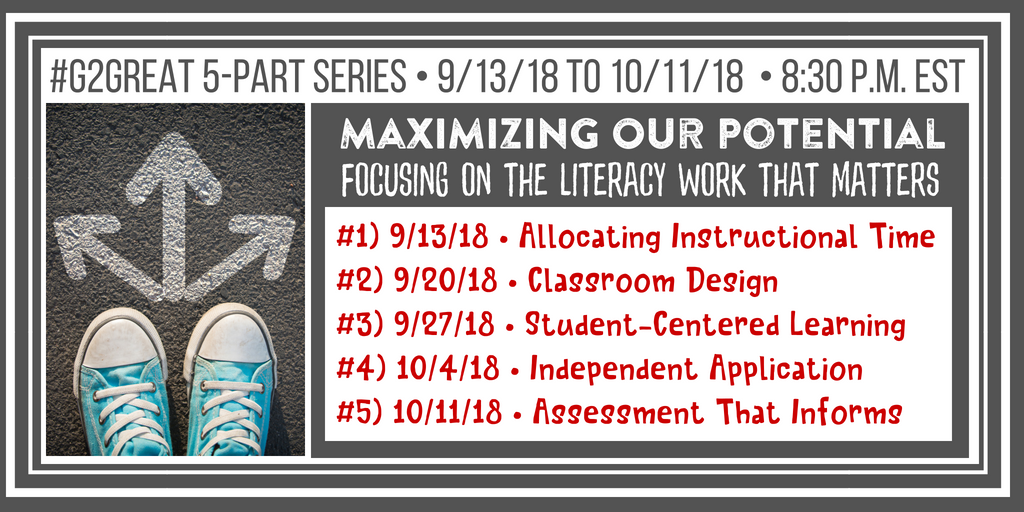

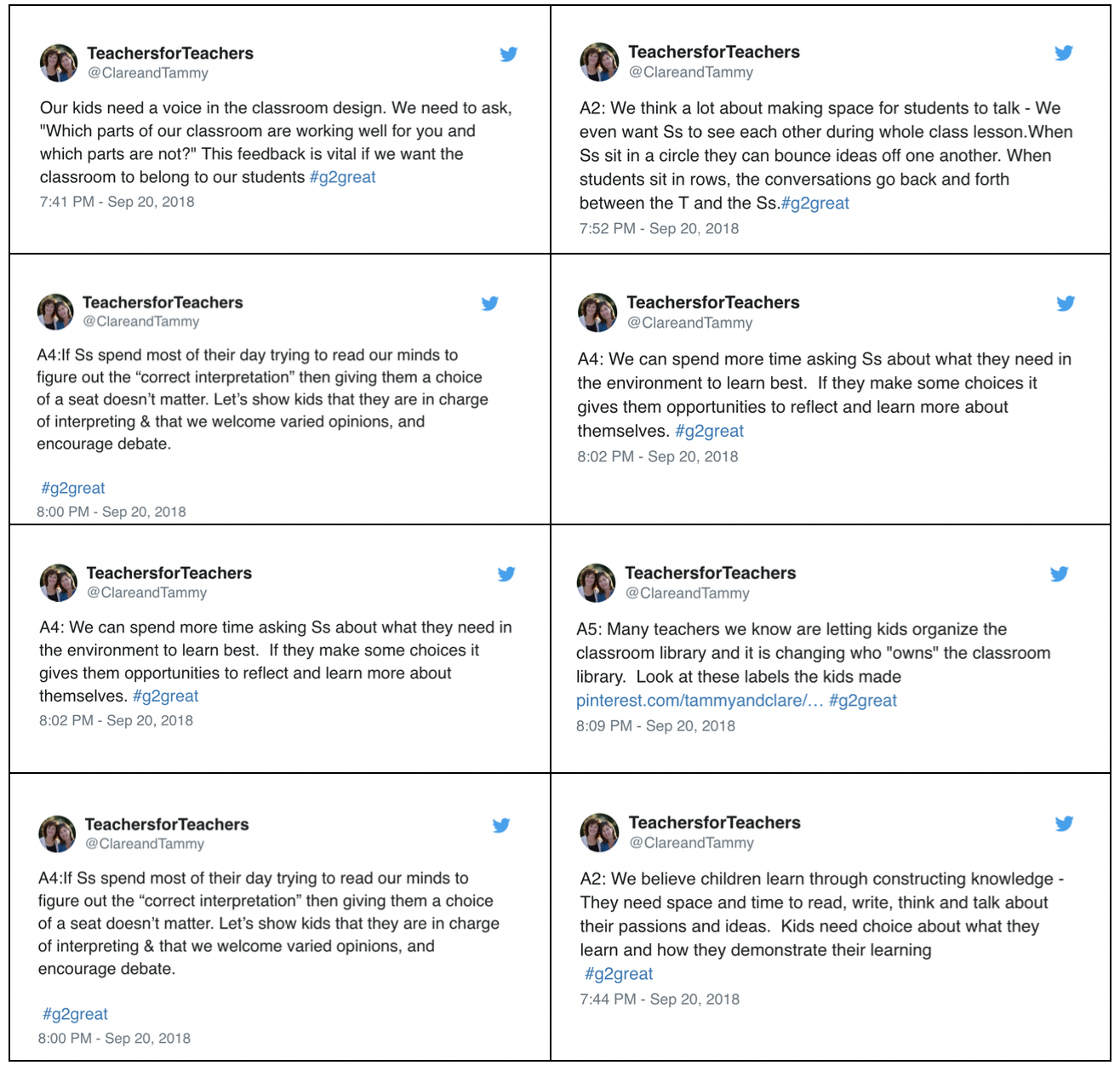

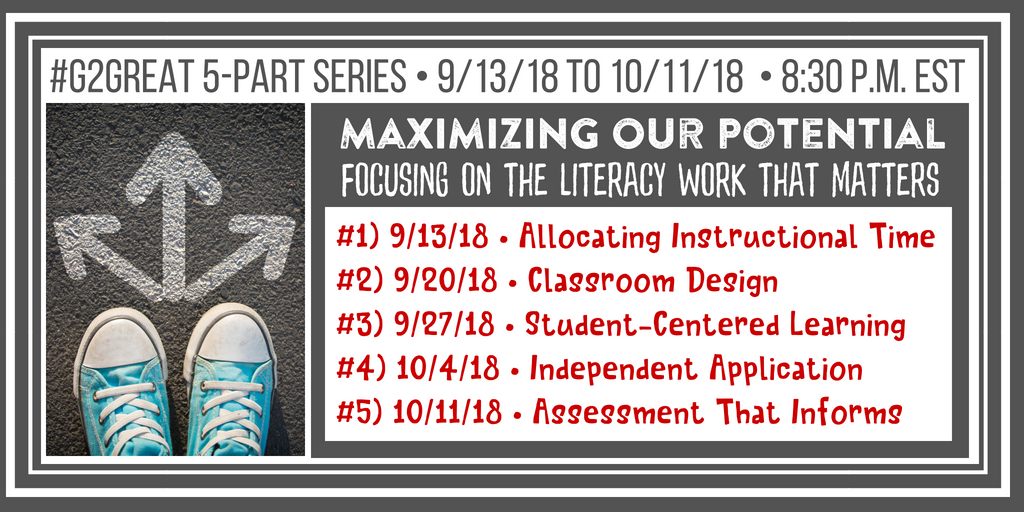

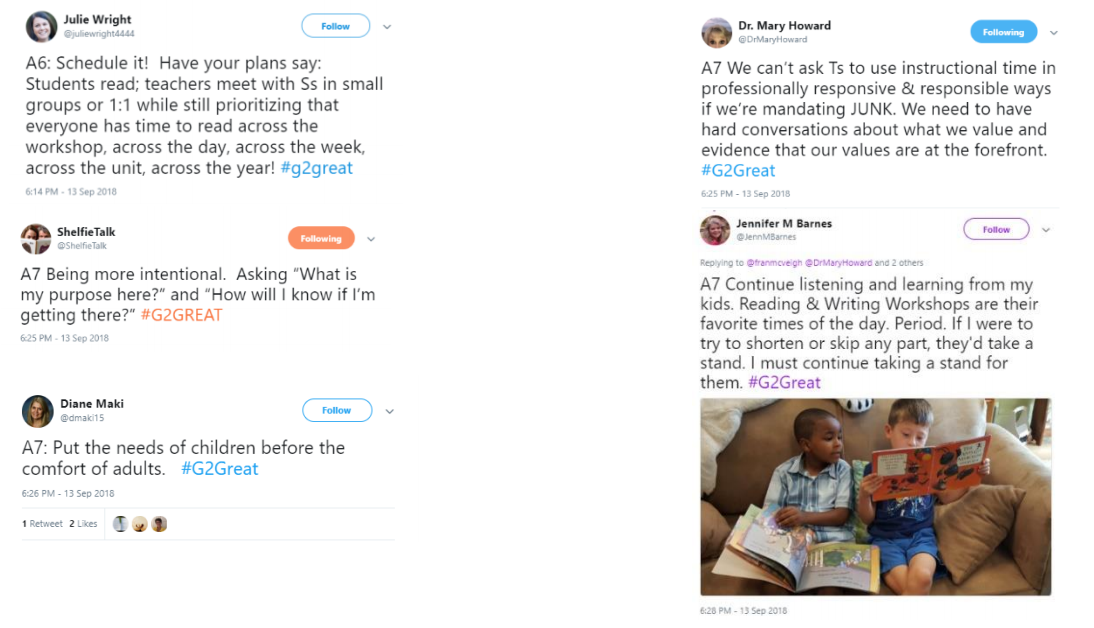

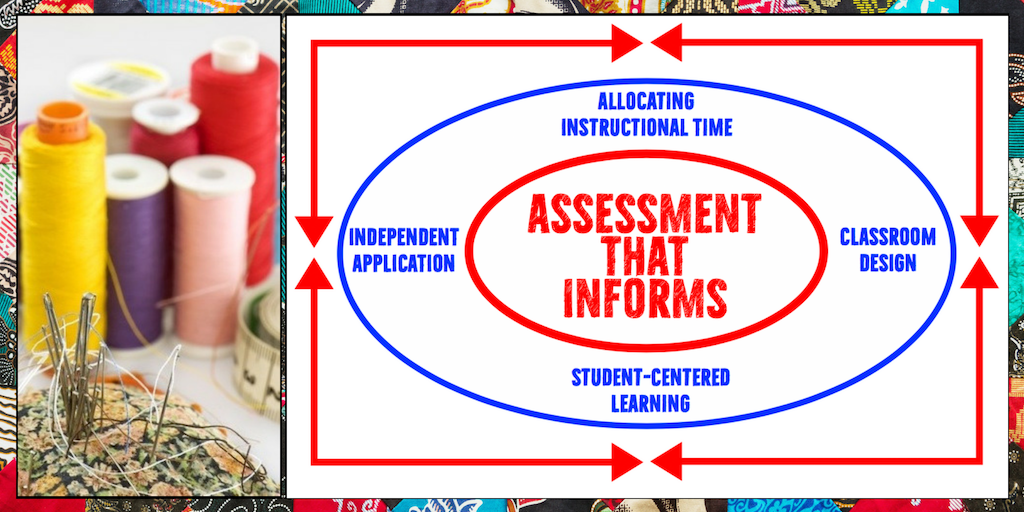

Part 2 continued with Mary Howard’s post:

Part 2 continued with Mary Howard’s post:  Part 3 continued with Jenn Hayhurst’s post:

Part 3 continued with Jenn Hayhurst’s post:  And that brought me to this chat and part 4: Independent Application

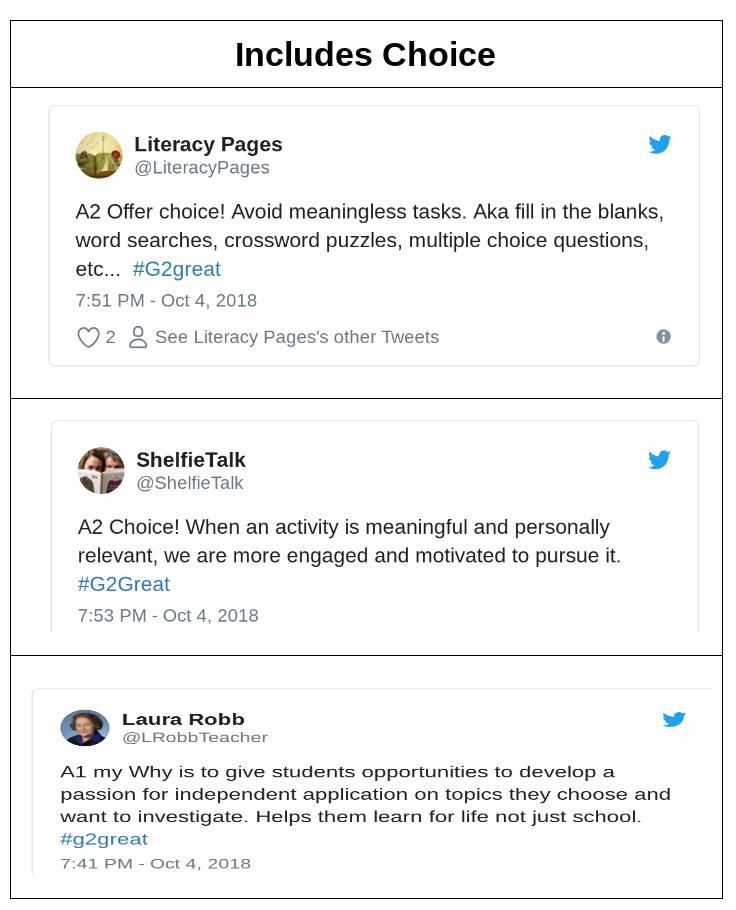

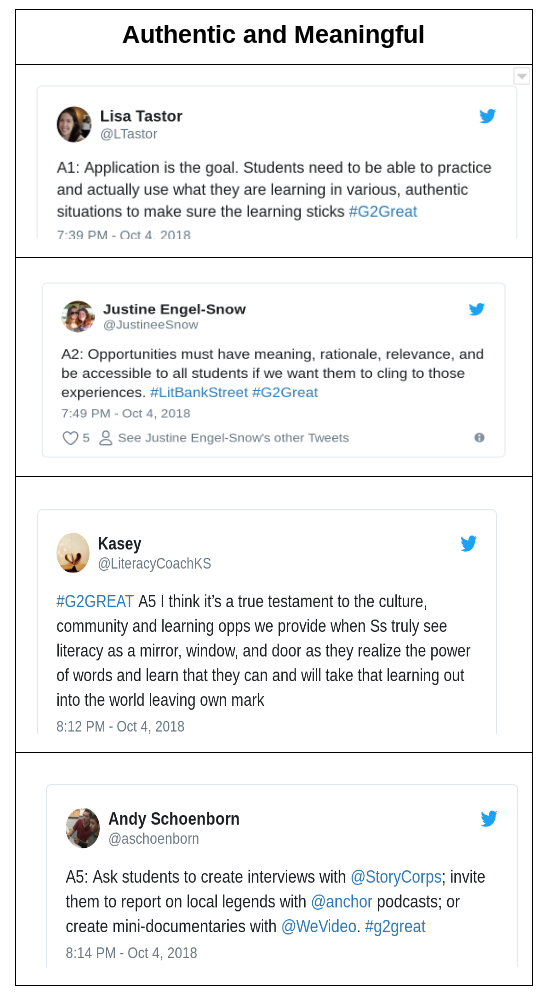

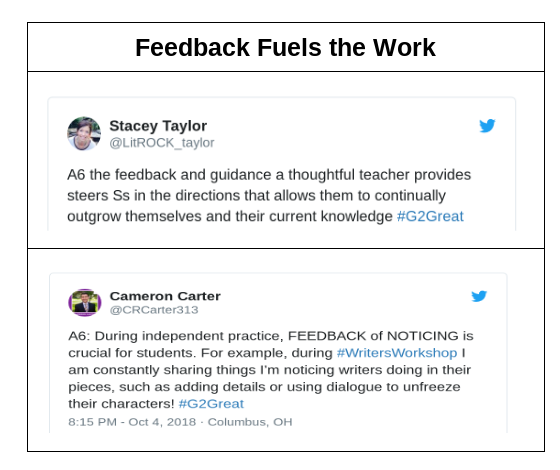

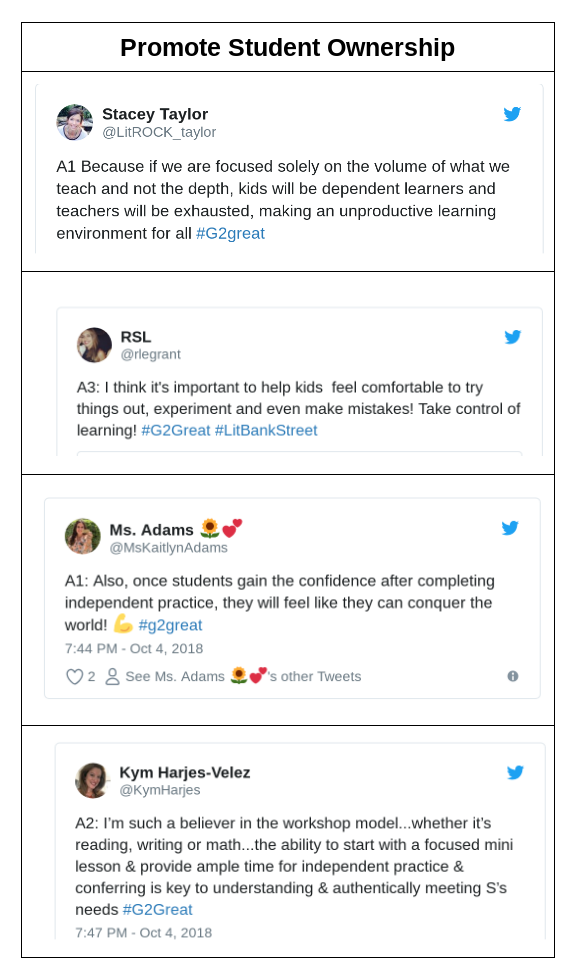

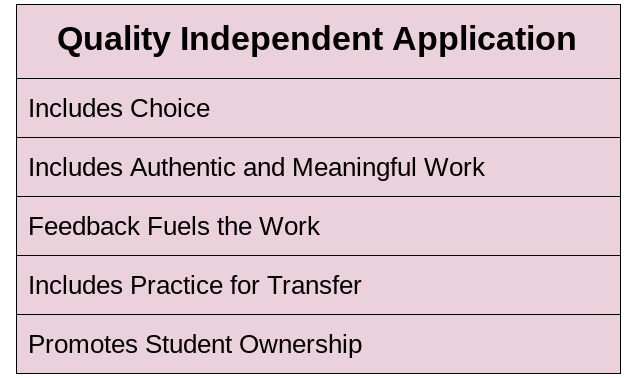

And that brought me to this chat and part 4: Independent Application Source Link

Source Link