By Brent Gilson 10/27/2019

I was excited for this chat topic and so grateful that my week to blog fell on this date. I start with the term above. When I think about the importance of empowering student voice, the importance of students knowing they are both heard and seen the critical importance of it becomes clear to me as I think about what the alternative might be.

A quick story of my greatest failure as a teacher. Two years ago I was teaching in a small, conservative (religious), mostly white community. In one of my classes, a student made the brave choice to come out as transgender. This was not an easy road, peers did not react with acceptance, bully behaviour was excused by parents as disagreements around morality and as teachers, we worked to try and protect this student from the intolerance that surrounded them. In the end, the student left our school and community. Their voice was drowned out by the voices of intolerance. I still think about if there was more I could do. In a job interview last year I was asked what my greatest failure was as a teacher. I tearfully recalled this moment it sticks with me. I have talked to the student since. They are happy in their new school. They are doing well, despite our failings to build a community that would accept them for who they are.

When we look at the importance of empowering our students so their voices are heard I think we need to consider two essential questions. First, do our students see themselves in our classroom? In our instruction? In our libraries? And Secondly, How does our intentional practice create a culture of community inside and outside our classroom?

Looking at the first, I remember listening to a Heinemann podcast with Lester Laminack and Katie Kelly which can be found here. In the podcast, a point that stuck out to me was in reference to books in the classroom. In what we as teachers choose to leave out. When I was teaching 6th Grade Lily and Dunkin was released. I bought it for my classroom library because of well… diversity( the intentions were good). A student read it and came to warn me that it might not be a good book for our classroom because there was a Transgender student in the text. A coworker and I often discussed if books would be acceptable in our community before putting them in the library. Looking back I wonder how many students struggled to see themselves in our classroom because of this concern of angry parents complaining about literature. I have always brushed off any worries that books might bring complaints but I didn’t necessarily promote the books. My intentional choice to not talk about these important texts gave permission for my students to not read them. This unintentional erasure contributed to my students’ inability to see anyone but themselves and what they viewed as “normal” as a part of their community. Most certainly it contributed to some of my students being unable to see themselves and how does one use their voice when they do not see themselves as part of the conversation?

Even the best of intentions in creating a classroom the reflects all of our students can go wrong. I started last year with the intention of building a classroom library that represented Dr.Rudine Sims Bishop’s ideas around mirrors, windows and sliding glass doors. I was building a library the was diverse in appearance but fell into the single-story narrative for many of the stories that featured lead characters of colour. It reminded me of University when my Professor shared an account of her niece coming home in tears because the “diverse” book they were reading featured African children with a monkey sitting on one of their heads. The kids all teased the lone student whose parents had emigrated from Ghana if monkeys ever sat on her head. I wonder how quick she was to share her voice?

As teachers, it is our responsibility to build a community that empowers our students. Empowers them to use their voices and also empowers them to grow, to learn and to welcome those who might not see the world with the same lens. I spoke about my missteps on this learning journey to highlight the lessons I have learned as a teacher. I am constantly looking at if my actions as a teacher elevate or erase and where to go next. To ensure we elevate I think there are times when holding tight to our convictions, that every child has the right to be seen, to feel valued and be respected and heard, is more important than our comfort. At times we need to speak up against the majority on behalf of the minority. We have to use whatever privilege we have and that might simply be as the adult in the room to be that champion for all of our students so that they know when they speak we will be listening.

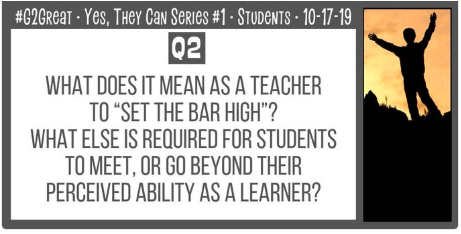

As I looked back on this chat I think of my students who have yet to find their voice, who do not feel quite comfortable enough to raise their voice. To participate as members of our community. I look at how I might empower them but also how I can empower those who are in the majority to work in our community to help others to see why this is so important. In the end, what makes us all unique is what makes the classroom so great. Providing a community that empowers ALL students will continue to move this important dialogue forward.

If you missed the chat this week you can take in all the amazing thinking on the Wakelet located here https://wke.lt/w/s/8qfX6R