by Mary Howard

On 6/20/19, #G2Great culminated our 5-part intervention series as we highlighted a central feature of this process: Designing a Flexible Bridge for Collaborative Intervention Coordination. I took great pleasure in writing this post since I also had the honor to write the first post in the series on 5/23/19: Positioning Tier 1 as Our First Line of Intervention Defense. My writerly bookends status seemed fitting considering these features reflect two essential factors that hold the entire intervention process together and can ultimately become what will enrich or diminish this process.

As I reflected back on our #G2Great chat and perused inspired tweets, I wavered in my quest to find a hook for this post. But the more I thought about the five descriptors in our title, the more I realized that intervention success is dependent upon our ability to understand each of those words individually. With this depth of understanding, we can then merge those words in a thoughtfully responsive way. Suddenly I knew it made sense to deconstruct the title word by word: Design, Flexible, Bridge, Collaborative, Coordination. After all, how can we create a thoughtfully responsive intervention merger if we don’t understand the critical role each descriptor plays within that merger?

With this in mind and in celebration of the conclusion of our five-part intervention series, I’m going to depart from my usual #G2great post by discussing these five words individually in order to emphasize the importance of each within the intervention process and then reflect on how those words will work in tandem to create that thoughtfully responsive merger of collective commitment.

Design

The word “design” brings to mind an active process of creating something that could support and enhance our vision for what we want to accomplish. One of the struggles that we have had in creating a powerful intervention process is that too many schools have been weighted down by a design based on flawed mandates and dictates that restrict our efforts rather than to afford us the freedom to create a design based on a wider vision unfettered by limitations. This design must begin with a clear understanding of our vision at a deeper level as we then to consider how we can bring a shared vision to life within a supportive foundation in that spirit. To do this we may need to get out of our own way by breaking down the ties that bind as we refuse to allow marketeers and warped ideas to blind us. What is possible in this design process will come into view only if we don’t let anything stand in the way of a design that would breathe life into possible.

Flexibility

But creating a design that would bring a shared vision to life is only the beginning. No matter how good our design may be, that design will be compromised by the flawed belief that any one-size-fits-all intervention view will ever be adequate. The choices that we make within our design must maintain flexibility of purpose as we identify intervention opportunities that are student-centered rather than other-centered. If interventions are not based on the unique needs of that child at that time, we miss the point. Our design is the foundation but it is flexibility that affords us an instructional playground with room to make the richest possible professional decisions on a day-to-day, moment-to-moment and child-to-child basis. There is an inherent danger of losing flexibility if we are more concerned about what is easy, cheap or fast rather than what is in the best interest of the child.

Bridge

I love the idea of a bridge that will maximize our design and elevate our ability to hold tight to instructional flexibility since it’s how we get from where we are to where we need to be. But a bridge assumes a two-way entry point from either end with ample room to meet in the middle and all points in between. Too often, schools create a design with a flexible view but then seem to believe that they have “arrived” and thus see no room for growth and change. The flexible decisions that we make within our design playground are always changing and growing as our children change and grow because our bridge allows for continued movement in any direction. Our success is dependent on our willingness to invest both the time and financial resources that supports long-term professional learning that will thus transform that learning into worthy instructional practices. But as teacher maneuver their way along our bridge, they need ongoing support, preferably through high quality coaching with respectful and timely feedback. Without this, our view along a pathway to a child-centered focus will always be blurred.

Collaboration

But even when we have managed to breathe life into a flexible design bridge centered on the child with the ongoing learning that leads us to professional empowerment, we’ll still fall short until we can invite respectful conversational dialogue to the thinking table. The collective impact of our intervention efforts can’t live in a professional vacuum so dialogue that revolves around the needs of our learners is essential. Interventions viewed from a lens of collaboration has the potential to transform our professional conversations into collective commitment for the greater good of our school, our teachers and the children we support, whether they are in interventions or not. Our combined professional wisdom requires us to embrace this shared learning as we grow into our best selves within a never-ending learning process. Our unwavering dedication to children is a reminder that we can find our way to excellence in the company of others. And as we grow as professionals, so our flexible design bridge grows with us. There is no end point of arrival for achieving this lofty goal. Rather we choose to courageously embark on a shared journey that is oft times riddled in the uncertainty that inspires even more passion-driven collaborations.

Coordination

That brings us to our final descriptor that could further enhance our efforts. We can have the most instructionally powerful flexible collaboration design bridge, but this is irrelevant until we consistently coordinate our intervention efforts within and across tiers. The first four descriptors will offer a common professional lens that makes it possible for every educator who is supporting this child to coordinate their efforts. But success is dependent upon cumulative knowledge of literacy research and our knowledge of the child in front of us. This child-fueled understanding has nothing to do with narrow data points but the daily informants that support our shared decision-making. To know the child assumes that we know the same child and not the one we purport to know individually. Our responsibility to this child will require our efforts to be inseparably intertwined so that we can use that cumulative knowledge to offer interventions based on intensive “in addition to” coordinated support. The minute we create a divide and conquer mentality, we are doomed since our professional choices must be mutually supportive and not at cross purposes. Through this coordinated effort along our collaborative flexible design bridge, our interventions will lead to the accelerated progress our students need.

THE INTERVENTION MERGER

And so, we come full circle as we bring our descriptors together in order to initiate the thoughtfully responsive merger our children deserve. Designing a Flexible Bridge for Collaborative Intervention Coordination is but an empty promise based on isolated words until we bring each descriptor to life in joyful integrated harmony in the company of children. This is the turning point where we are able to elevate our intervention impact within and beyond the intervention process. For too long we have celebrated narrow ideas based on the shallow terminology that gives us nowhere to go. No matter how grand that terminology may be, those words are meaningless until they come together in celebration of student learning. And we owe that level of dedicated commitment to each and every child.

But now we need to blend the key components of the intervention process one step further. My two writerly bookends reflect only the first and last chats in our series, but the term “series” implies that one topic cannot stand alone. This is certainly true in this case and thus the reason we have three other topics that are all equally critical. If we look to our umbrella title in the series: Rethinking Our Intervention Design as a Schoolwide All-Hands on Deck Imperative and then reflect on each of the five topics in combination, we can again see how each of our parts work in combination for the greater good of the whole:

Intervention Series

5/23/19 (#1): Positioning Tier 1 as Our First Line of Intervention Defense written by Mary Howard

5/30/19 (#2): Embracing Books as our Strategic Intervention Heart and Soul written by Jenn Hayhurst

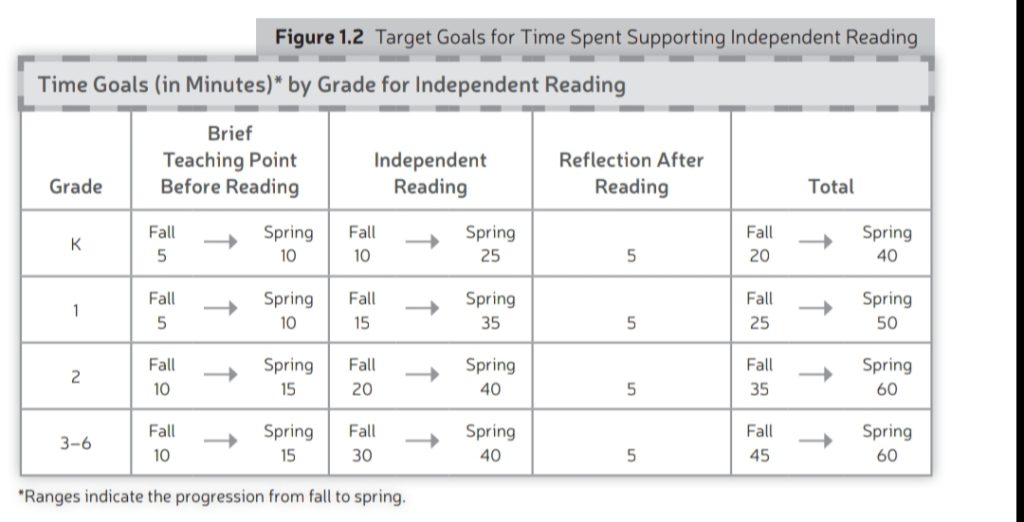

6/6/19 (#3) : Framing Increasing VOLUME as Our Central Intervention Goal written by Fran McVeigh

6/13/19 (#4) : Creating a Common Lens Across Tiers for Explicit Instructional Interventions written by Valinda Kimmel

6/20/19 (#5): Designing a Flexible Bridge for Collaborative Intervention Coordination written by Mary Howard

All five of these important topics are key considerations within any thoughtfully responsive merger that has the potential to translate into intervention excellence. I believe that this spirit of excellence is the only option we have and one that is worth fighting for in our schools.

MY FINAL REFLECTIONS

Before the chat began, we shared one of my favorite Seth Godin quotes that seems like a perfect closing to this post. Our intervention efforts have resided on shaky ground since IDEA 2004 made RTI our intervention reality. Given the research on our lack of success within this process, we need a new reality – a vastly improved reality. We have focused our intervention attention thus far too heavily on the chocolate and as a result have ignored the oxygen that would put us back on terra firma. The oxygen we need will only come when we can refocus our attention on the intervention process from a broader lens. Bringing our new intervention reality to life will require us to know our WHY from a much deeper level so that we can use this to translate our WHAT and HOW in the most purposeful and yes, thoughtfully responsive merger. It is my deepest hope that we will be able to make this reality transformation in our schools in the name of our children.

In the end, that’s the only intervention outcome that matters!