by Mary Howard

You can access our Wakelet chat artifact here

On 4/14/22, we had the great pleasure to welcome an old friend to our #G2Great guest host seat. Christina Nosek first joined our chat with co-author Kari Yates on 6/7/18 for their book, To Know and Nurture a Reader: Conferring with Confidence and Joy (2018, Stenhouse). This week Christina returned to help us explore her amazing new book, Answers to Your Biggest Questions About Teaching Elementary Reading (2022, Corwin)

Christina opens her book with a loving hat tip to her first-year mentor, veteran teacher Midge. In celebration of the “Midge inspired mentors” that every teacher so richly deserves, we shared Christina’s words below during our chat that is a foundational centerpiece of professional dedication.

In one sentence, Christina offers three essential reminders:

1) Find a mentor who will set you on a success trajectory (and stay on course)

2) Acknowledge the never-ending role of your professional quest for learning

3) Keep children at the ver center of your efforts from the first day to the last

These three beliefs reflect the heartbeat of Teaching Elementary Reading and are intricately interwoven across the pages of the book. Through her words, we are consistently asked to verbalize, internalize and individualize our beliefs often and with a critical lens. It’s worth adding that while our first mentors launch a path to professional excellence, our need for mentor figures continues across our careers. I have been blessed to have countless mentors across fifty years and counting who inform and support my thinking even now. Christina models deep respect for the mentorships that will sustain us even in the most of challenging of times if we are willing to take the time to find and access the inspiration and information they so generously offer us and put it into glorious action.

In each of our #G2Great guest chats, we ask our authors to respond to three questions that offer insight into their book WHY. Since our first question directly reflects the mentors who support us, let’s begin here:

What motivated you to write this book? What impact did you hope that it would have in the professional world?

When I was a first year teacher, I was mentored by a dedicated and loving grade level partner named Midge, who I discuss in the introduction of the book. I was so fortunate to have a mentor to turn to whenever I had a question or concern around the teaching of reading. Many teachers do not have a Midge to mentor them as they enter the profession. I hope teachers can turn to this book in the way that I turned to Midge many years ago.

One of the wonderful things about the entire Corwin Five to Thrive Series is that they are all positioned around essential “guiding questions.” These questions are unique to each book in the series and offer a reader friendly, belief driven experience. Christina poses and responds to six essential questions that include five key areas:

1) community (pages 8-35)

2) organization and planning (pages 36-67)

3) instructional principles (pages 68-101)

4) assessment (pages 102-125)

5) student agency (pages 126-145)

NOTE: I linked sneak peek chapter descriptions on Christina’s wonderful blog

These five chapters are tied together with next step words of wisdom in chapter 6 (pages 146-148). To add to this question-based framework, each of the five umbrella questions have 7-12 subquestions as well as additional questions that accompany wise instructional suggestions and advice across the book. With professional grace, Christina gifts us with our own mentor between two covers.

When we are honored to have an author lead our #g2Great chat twitter style discussion, we ask them to craft their own questions. We do this because it gives us a glimpse into what each author believes are the most relevant underlying book ideas from their perspective and how we can translate the passions that fueled their writing into a chat format so that those same passions will rise to the surface in the form of a twitter discussion. Because we value their responses to their own questions, let’s pause for moment and look at our six questions with Christina’s thoughts about each one in the course of the chat.

TWITTER QUESTIONS/RESPONSES

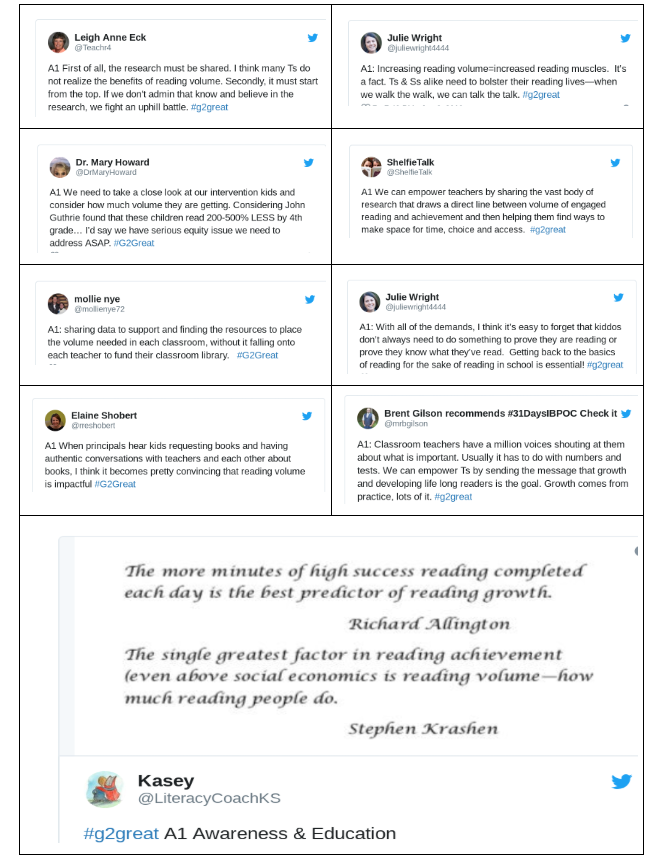

Q1 Drawing from the “Five to THRIVE” series theme, let’s establish our #G2great baseline. What do you value most in reading instruction that is designed to help children THRIVE? What practices are non-negotiable?

Q2 What are specific ways that teachers can grow and nurture the reading communities in their classrooms?

Q3 Describe one high-impact instructional method or routine that both engages students and stretches them as readers. How do you know the method/routine works for your students?

Q4 What does it mean to use reading assessment in the service of students? What does this look like in the classroom?

Q5 What advice would you give to a new teacher who is learning about the teaching of reading or to a veteran who wants to make their reading instruction more authentic?

Q6 One goal of our #G2Great chats is that you will take action after the chat. What have you seen or heard tonight that you a) want to learn more about? b) want to implement? Or c) want to revise to meet the needs of your students?

Christina’s responses clearly illuminate what matters deeply to her, both in her book as well as over twenty years in her own classroom. Let’s extend this by sharing her response to our second question on her book takeaway hopes:

What are your BIG takeaways from your book that you hope teachers will embrace in their teaching practices?

My hope for teachers is that they embrace following the lead of their readers in the classroom. I want teachers to feel inspired to teach the readers in front of them rather than follow a canned curriculum page by page. Afterall, we are teachers of children, not of curriculum.

In Teaching Elementary Reading, Christina heightens our responsibility to envision a broader perspective that is sorely needed in our schools right now while also cautioning against the one-size-fits-all approaches and practices that have long maintained a stranglehold in our schools. She asks us to expend our time and energy in the most effective, productive, and yes, joyful ways by making a commitment to let go of those things that set up roadblocks to what matters most. This process of “letting go” reminds us of the harmful impact on our learning day when a clock rigidly dictates every choice we make. Christina reminds us that we always have a choice about how we spend the important moments of our day and that those choices clearly reflect that we see ourselves as “teachers of children, not curriculum.”

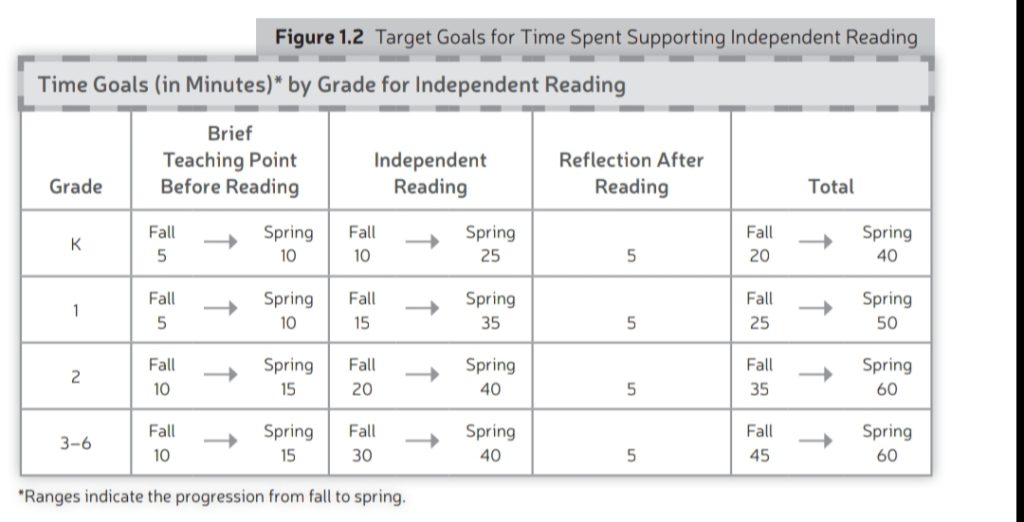

One of the choices Christina enthusiastically asks us to embrace is reflected in this second quote above we shared during our #G2great chat. This is not only a choice that she embraces in this book, but one that she has embraced in her own classroom since I have known her. Volume is a topic that Christina holds dear and she approaches this with deep conviction for three areas of reading she refers to in her book: reading to learn, reading to be entertained, and reading to grow.

Before I close this post, let’s return to Christina’s third question:

What is a message from the heart you would like for every teacher to keep in mind?

It’s ok to feel that you do not have all the answers right now. Learning and growing as a teacher is a continual journey. Never stop seeking out the ways to best support your students. I am a very different teacher than I was even five years ago. I hope to teach differently five years from now. Serving students is all about learning and growing.

The most important thing you need to know right now is that you are on a continual learning journey to be the kind of reading teacher who values your own learning because you know your students’ learning depends on it.” (p 6)

MY CLOSING THOUGHTS

Early in the book, Christina cuts to the chase and focuses her attention on what matters most in our teaching as she brings Teaching Elementary Reading to life across each page filled with essential advice.

“Good teaching always involves following the lead of your students above all.” Christina Nosek, page 17

Every suggestion, every idea, every description and every question Christina posed and responded to so eloquently brings us back again and again to the reason for all we do – our students and what is in their best interest. Teaching Elementary Reading is a book of questions; but even more than that it is about crafting questions that rise out of curiosity and commitment to children and using them as a springboard for the view that teaching is a process of reflective introspection that helps us to make the best possible choices on their behalf.

As I began writing this post and revisiting the incredible questions Christina crafted to guide her readers on their own journey, it occurred to me that generating questions can initiate a powerful process of exploratory discovery. Just as I am certain that Christina fine-tuned her thinking in the course of breathing life into each question, we too could do the same. Just imagine if teachers created a growing list of BURNING questions, using those questions as the gentle nudge that can lead to a “continual learning journey to be the kind of reading teacher who values your own learning because you know your students’ learning depends on it” Self-discovery begins with the questions that drive us to know more, to understand more, to be more and to apply those things in our teaching. And when those questions inspire us to reflect on our innermost beliefs and commitment to kids, it can awaken the best kind of teaching and learning that occurs in the company of and in the name of kids.

I am very privileged to call Christina Nosek a dear friend, making this opportunity to craft our #g2Great post this week an added honor.

Thank you, Christina!