By Fran McVeigh

What is a message from the heart you would like for every teacher to keep in mind?

I think that we have made writing in schools a task, heavy labor. We need to connect writing with play, with improvisation, pleasure, and friendship.

Tom Newkirk, email.

Tom Newkirk’s response hurts my heart. My teacher heart. My writing heart. My parent heart. My grandmother heart. My literacy being just hurts.

It hurts my heart because I also know it to be true. Writing has become a “chore” in many classrooms, whether it is the kindergarten classroom where students COPY sentences from the board daily, the fourth grade classroom where students respond to daily writing prompts from the teacher, or the middle school classroom where students are engaged in formulaic argument writing day after day. Of course, not all classrooms have reduced writing to tasks and heavy labor. But many classrooms in middle schools and high schools across this country teach “how to write a sentence”, “how to write a five sentence paragraph”, and “how to write a five paragraph essay”. Disheartening. Disillusioning. Deadly for a writer’s heart.

Necessary?

Appropriate?

Well-intentioned?

Expected?

Required?

Where do your writing experiences fit? Consider the stories in this blog post. Do they parallel your experiences? You will see stories of writing from writers, teachers of writing, and wisdom from some writing experts!

And now, back to our regular format. Typical posts begin with our title slide and some background on our author or topic. So let’s resume our regular program!

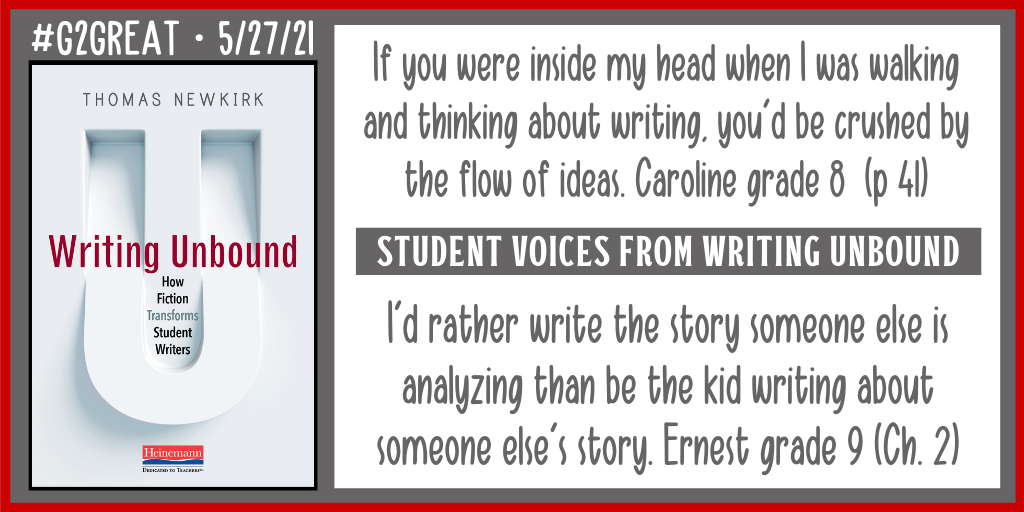

Our #G2Great chat on Thursday, May 27, 2021 with Thomas Newkirk tackled a variety of issues about writing that all writing teachers need to consider. We were discussing his newest beautiful book, Writing Unbound: How Fiction Transforms Student Writers, which is student-centered, qualitative research. Research carefully and respectfully gathered from students and teachers! This was a return visit to #G2Great for Tom who hosted in January of 2018 to discuss Embarrassment and the Emotional Underlife of Learning. His previous books, Minds Made For Stories and Holding on to Good Ideas in a Time of Bad Ones continue to grow our thinking about current fads as well as what we need to hold tightly to in order to realign and reignite our actions, visions, and beliefs about writing instruction.

I love to write. I write best when I have choice in topic/content and organization. I know that’s not always possible. I’m not comfortable writing fiction and stories are still hard. Not fun. Not pleasurable. But in recent years I know that stories cultivate friendships as I have learned through Two Writing Teachers’ Slice of Life. I have searched for the source of my failure feelings with fiction. One factor: I came from the era when we were taught that our writing should never include “I” or “you”. I and you were consistently “red-inked” by multiple teachers. Consequently it became easier to avoid situations where an “I” or “you” story felt more natural. Avoidance seemed to work. A second factor from my own school days – I don’t remember ever feeling that my teachers were WRITERS so there was little encouragement. And thirdly, writing was often a task or assignment to be completed only by students. Fiction . . . It was never presented as a choice in junior high or high school.

So here are two quick stories from my writing life.

My obsession with improving writing instruction began with a course on writing with Sue Meadows after I had been teaching for a decade or two. Sue was a local district administrator with ELA Curriculum responsibilities. And then I was hooked. Atwell, Graves, Harwayne, Hansen, Murray and Spandel were just a few of the writers that I was studying. I became a sponge. I went to additional training on the “6 Traits” and thoroughly absorbed the notion of aligning instruction with the rubrics used in assessment. Through assessment academies, I also went on to co-lead district-wide writing assessment. Each opportunity led to increased understanding and typical me, I never waited for “someone else to bring the learning to me”. Instead, I continued to search for more information about writing processes and the different genres of writing. My goal: Continue to grow my own understanding of “Quality Writing”!

In November of 2014, I attended and presented at NCTE in Baltimore. One speaker in a panel presentation stood out: Tom Newkirk. I was fortunate to have a seat in the packed room. I chuckled with conference attendees when Tom said that a “hamburger” organizer was an “even bigger insult to a hamburger” besides it often resulted in boring, dull, tired writing. I appreciated his emphasis on student choice writing even as I knew that would be a tough sale for some of the high school teachers in my region. Since that date, my collection of Tom Newkirk’s books has risen exponentially.

What motivated you to write this book? What impact did you hope that it would have in the professional world?

I felt that there were several “disconnects.” Students are immersed in fictional narratives–movies, video games, books, TV. But they are rarely given the chance to write in these forms. That’s one disconnect. Another is the profusion of fictional writing outside of school (e.g. fanfiction) and its absence in school. I think schools are still operating on an outmoded idea that reading is the dominant form of literacy, and that writing, particularly fiction writing is for the talented few. That’s no longer the case Finally, we praise the benefits of fiction reading as creating empathy and self-understanding. Why can’t the same be said for writing fiction–creating characters? So my goal is to open space for a kind of writing that students are eager to explore.

Tom Newkirk, email

Opening space. I wouldn’t have written about video games until my grandson introduced me to Mario Brothers. But I still don’t know enough to write about it. Fiction reading is my absolute favorite. Fiction writing is my absolute least favorite writing. I don’t know the expectations. I haven’t written enough fiction to write it even “passably” well.

What do you know about fanfiction? Here’s an excerpt from fanfiction.net under “Books”.

What is the role of fiction in our students’ lives. Are students being asked to READ fiction but NOT write fiction? Isn’t that ironic?

This leads me to the final question that we ask our authors.

What are your BIG takeaways from your book that you hope teachers will embrace in their teaching practices?

I hope that they will open their practice to allow fiction writing–not even necessarily requiring it, but making a space for it. I hope that they will listen to students–about what they want to write, and their experiences writing. I hope that teachers themselves try out fictional writing. I hope that teacher prep will make a place for fictional writing as prospective teachers move toward their career. And I hope that our instruction will avoid formulas and instead look inductively to how writers actually write.

Tom Newkirk, email.

Many hopes: allowing fiction writing, listening to students, trying it themselves, teacher prep, avoiding formulas and examining real writing.

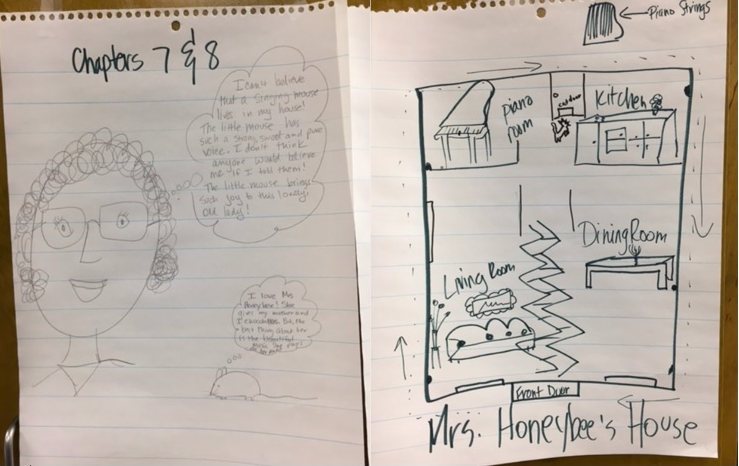

Now that we have looked at Tom’s goals for his book and heard two of my stories about writing, let’s get to the heart. What are students saying about their writing? These two quotes were part of the #G2Great chat.

Some people don’t get the “What if?” Some people like the easier what ifs of what if this happened to so-and-so, in modern day. Other people can’t stand that kind of stuff and that is what fantasy is for.

Helen, quoted in Reading Unbound

I can relate to Caroline’s “flow of ideas” as drafting is a messy spot in my head with ideas ping ponging everywhere. As for Ernest’s ideas, I think I would pass on the writing a story and the analysis. Helen speaks of the freedom of “What if?” in fantasy writing. Maybe my niche in writing would be to verify more informational text/ideas that could be added?

What I take away from all three students and Tom’s tweets is that writing stems from many sources and that we must trust students because 1) they do know a lot and

2) there is no one way for writing to go!

And they, the students, know it!

But I don’t see that flexibility for students or even for teachers of writing in many of our schools.

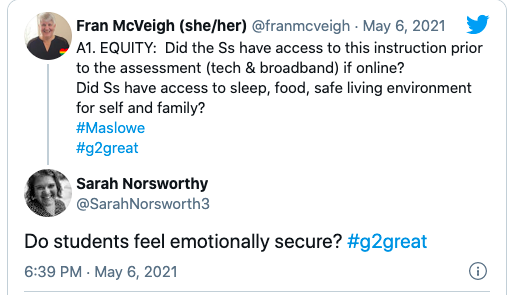

The wakelet contains so much wisdom from Tom Newkirk and the many teachers and #G2Great friends who join us weekly. The remainder of this post is going to focus on just this one question.

Why has fiction writing diminished in the upper grades?

- Call for college prep writing and Common Core Standards

College and Career Ready

I call this bias, the cattle-chute vision of preparation. This is why a creative writing elective is often viewed as a kind of indulgence, unrelated to the main mission of high school writing. I think of the advice that the young Dav Pilkey received: that he would never make a living drawing silly cartoons about a principal who thinks he is Captain Underpants. That, of course, was several million book sales ago.

Tom Newkirk, Writing Unbound

Some folks do not believe that fiction writing has a place in academia; fiction writing is for beginning writers. That leads us to reason two.

2. Fiction is too easy and not rigorous enough.

… narrative is not a discrete type of writing—it is our primary mode of understanding, and it underlies all writing.

(Newkirk 2014)

It simply makes no sense to deny students the opportunity to write in the genres they choose to read.

3. Lack of personal perception of competence and conviction that fiction fits into daily writing instruction

Fiction writing can also offer an experience that I feel is crucial to enjoying writing: the feeling that writing generates writing—that a word suggests the next word or phrase, that we can listen to writing and sense what it suggests. And even for teachers committed to fiction writing, it’s a tough fit in the curriculum. Stories take time and are often far longer than more contained forms of writing—an editorial, for example, which can be held to a few paragraphs.

Tom Newkirk, Writing Unbound

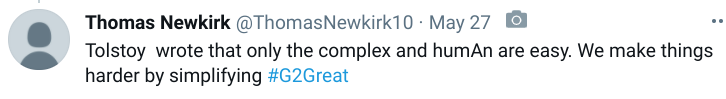

Not all writing is equal. Writing-like activities are available that may or may not parallel reading activities. Tom calls these peripherals. It may surface in writing prompts, vocabulary or comprehension work.

In Conclusion . . .

As I searched for a way to conclude this post I was drawn back to these questions that Tom Newkirk used to close chapter 2 of Writing Unbound. What are your answers? How would your students answer them? They might be a source of reflection on past instruction or planning for next year’s instruction!

So we need to ask: Can we inhabit the dizzying worlds that Ernest and his friends create? Can we experience with them the dangers and narrow escapes? Can we even help them think through their plots, imagine their characters? Can we play their game? It’s a challenge worth taking up.

Tom Newkirk, Writing Unbound

LInks for Additional Resources:

On the Podcast: Writing Unbound Link

Sample chapter from Writing Unbound Link

A Confession from Tom Newkirk about Writing Unbound Link

Bridging the Divide between Creative Writing and Literary Analysis Link

Added 06.07.2021: “The Power of Writing Collaborative Fiction” by David Lee Finkle LInk