by, Jenn Hayhurst

Have you ever gone to a national conference? If you are a teacher, going to a national conference gives you more than just information. It bonds you to all of these wonderfully generous people who are at their truest selves, gifted teachers. They help us to learn through their wit and insight. They are genuine, and at times even poignant. I once attended an NCTE conference where Tom Newkirk – wait, I could geek out here and go on about how much I admire this man, but I digress… shared a deeply personal story about his wife’s cancer. He recalled how when they were reading about potential treatments, they were reading it as part of a story they were telling themselves. Their purpose for reading was vastly different than the author’s intent for writing. His message to us? It was to enlighten but also to remind us that learning through story is powerful because we are wired for story from the start.

“Stories are how we understand the interrelationship of events. Stories are at the heart of how we learn because they create memories and provide details we want to know. Stories grab us in a way no list of facts could ever do.”

Jim McElhaney review of Newkirk’s Minds Made for Stories

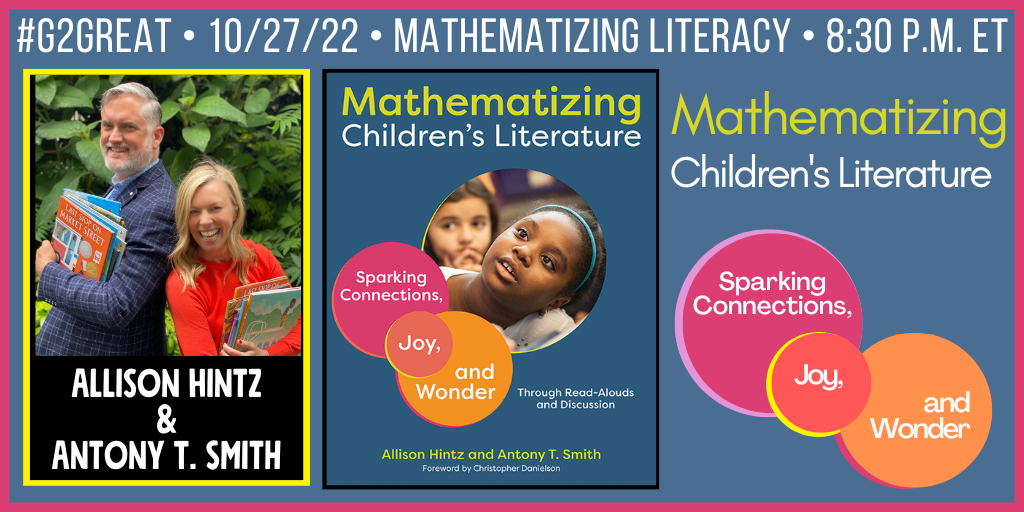

On Thursday, #G2Great welcomed Allison Hintz, and Antony T. Smith to #G2Great, to lead a discussion around their book, Mathematizing Children’s Literature: Sparking Connections, Joy, and Wonder Through Read-Alouds and Discussion. Mary asked me if I would write the blog post and I was excited to write about this important concept. What would happen if we viewed real children’s literature through a math lens rather than viewing literacy and math as separate aspects of the curriculum? This idea of mathematizing children’s literature would extend an intriguing open invitation for math learning in a whole new way. I was hooked! I love the idea of giving learners space to ask their own questions because it rings true. Teaching through the art of a well-constructed question; one that generates more questions is a deeply held personal belief for my own teaching.

We Read Professional Books to Learn From Others

Allison and Antony have real expertise in mathematizing children’s literature. During a pre-chat interview they said:

“Our collaboration integrating math and literacy within the context of children’s literature is joyful! In working for eight years with teachers, students, children’s librarians, and families, we have learned a great deal about children’s thinking and how to nurture their mathematical identities. We also have seen the powerful ways stories provide a creative and engaging context for exploring our world as mathematical sense-makers.”

I was a kid who was labeled as a strong reader and writer, but not necessarily a mathematician. Teachers know (or should know) that the labels we use to describe children will stick, and I am not an exception. How could I add to a child’s mathematical identity when I don’t feel up to that challenge? The answer was immediate. I would need more professional development and then experience in how to ask open-ended mathematical questions. For my first attempt at generating an open-ended math question, I used the book, Last Stop on Market Street. It felt like a lame first attempt when I wondered how much the bus fare was but it also gave me insight into what children might ask in the early stages of learning. Then I read what Nadine and Mollie had to say:

Ok, their wonderings felt superior to mine, but I was not deterred to try again. This time, I asked the experts what they thought about my favorite (new) picture book, Evelyn Del Rey is Moving Away.

Look at what Antony suggested…

Three Big Takeaways

● Almost any story can provide a meaningful context for mathematical thinking and discussion.

● When we ask children what they notice and wonder about we are providing an opportunity for young mathematicians to be curious as they explore and share their questions and ideas.

● Math and literacy work powerfully together! Mathematicians reason, analyze, predict, and construct meaning; readers ask questions and identify and solve problems.

As I consider this, and everything else Allison and Antony shared during the chat, I can’t help but think about how mathematizing children’s literature may even generate deeper connections to characters children love. Maybe by having those deeper math conversations we will be contextualizing these characters in a way we have never done before as we make the characters children love even more present in their lives. Maybe, when they leave school they might wonder about how many bricks are in their own houses. I am going to work on my own issues about feeling inadequacies as a mathematical thinker to extend this invitation to my students too. I invite you to read this wonderful book because there is so much potential for these math conversations to make learning even more nuanced in ways that are novel and connected to their lives. That is a recipe for learning and transfer, but Allison and Antony really said this best:

“How children see themselves–and are seen by others–as mathematicians is significantly shaped by their experiences in classrooms and school communities. Through mathematizing children’s literature, we have the opportunity to affirm a child’s mathematical identity and agency while also nurturing them as readers.”

We are so grateful to Allison Hintz and Antony T Smith for sharing their expertise and teaching us all about Mathematizing Children’s Literature.

To learn more about how to link math and literacy you may also search our website to read Mary’s post: Hands Down, Speak Out: Listening and Talking Across Literacy and Math, and please visit Stenhouse Publishing to view videos and accessible resources for Mathematizing Children’s Literature Sparking Connections and Joy Through Read Alouds and Discussions