By Guest writer, Travis Crowder

Years ago, while in college and trying to find my way as a writer, I sat at the desk in my dorm room and stared hopelessly at a draft of my senior thesis. With just two weeks to go before the end of the semester, I was frantically trying to re-write the thesis I had turned in several weeks before. If I didn’t finish this paper, I wouldn’t pass the class. And if I didn’t pass the class, I wouldn’t graduate.

The margins were filled with the wide loops and flowing script of my professor’s gorgeous handwriting. In graphite, Dr. James had marked nearly everything that didn’t work in my essay. Organization, word choice, and inaccurate references were just a few of the problems she meticulously noted in the essay’s perimeter. More than anything, she implored me to re-read my paper and figure out what I was trying to say. I have no recollection of what I did to “revise” my thesis, but I typed and re-typed until I reached the last page. Then, I opened an email and re-submitted my work. Mercifully, Dr. James responded that the paper was acceptable, so I sent it to the literature department secretary, who promptly printed it, bound it in a portfolio and sent it to Dr. James’s office. It was finished.

In the last class, each of us in the thesis seminar received a hard copy of our work with final comments and a grade. When Dr. James handed me my paper, I glanced at the first several pages, read the new comments she had inscribed in red ink, then pushed the bulky thesis into my backpack. I carried the essay back home at the end of the semester, eventually surrendering it to the trash. To this day, I do not know what my final grade was.

When I think about revision—returning to writing and reimagining, rethinking—I flip the pages of my memory to that time in college so many years ago. I could spend paragraphs of this blog post bemoaning the lack of writing instruction and revision practices from my K-12 school years, but here’s the rub: my lack of preparation was not/is not atypical. Students enter college every year without adequate experience with authentic writing and revision practice. I know because I was one of them.

I even hesitate to use the word practice as it connotes something not real. My point, however, is that each experience, each time we put pen to paper, is a form of practice. This blog post, while written for publication, is me practicing. It will stand among the other pieces I’ve written, supporting what I decide to write next. In public school and college, I wrote a lot. A lot. But I didn’t practice revision. I didn’t know how. My “revision” included a hyperfocus on grammar and word choice. Don’t get me wrong—grammar and diction have an important function. But this hyperfocus affected the quality of my writing. Unfortunately, the roots of this habit burrowed deeper, and I carried it into my teaching life.

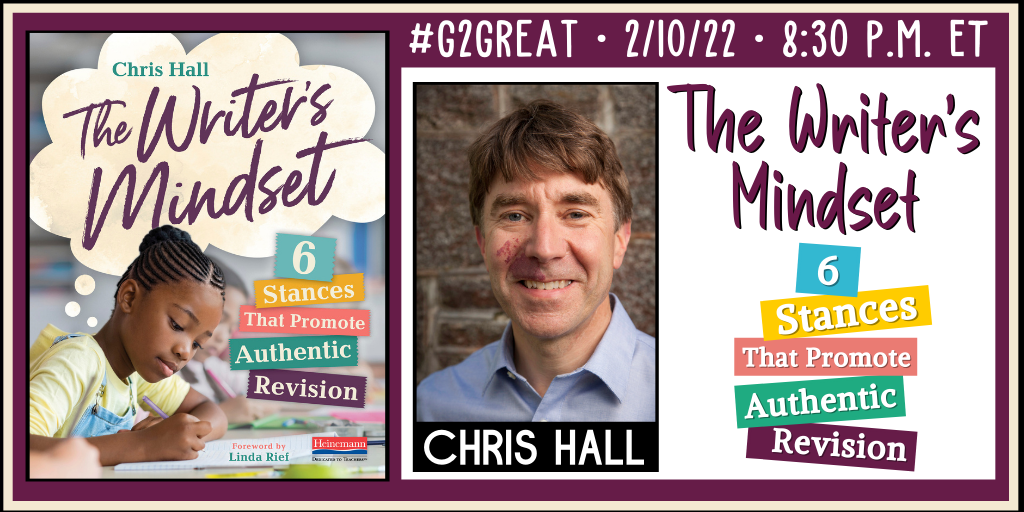

Chris Hall’s (2021) book, A Writer’s Mindset, is a text I wish I had had when I started teaching, but instead of lamenting what I didn’t have, I will carry his wisdom as I move forward. While my writing life has changed and my approaches to teaching writing are much stronger than they were, Chris’s book sits among some of the best books about writing instruction I’ve read. This book is a journey, a crescendo of hope, that explains and models how revision changes students’ writing and students’ self-perception as writers. Chris manages, with clarity and precision, to center students and joy in the act of revision.

In his book, Chris identifies six stances: metacognition, flexible thinking, transfer, optimism, perspective-taking, and risk-taking. From his perspective, these stances, or mindsets, lift students’ ability to revise, taking their writing from where it is to where it could be. After reading his book and underlining gobs of sentences, dog-earing multiple pages (yes, I’m one of those readers), and sticky-noting intersections I want to take to my notebook and explore with writing, I agree.

For example, take Chris’s chapter about optimism, the second stance he explores. Optimism in regard to writing isn’t, as he states, about cheerfulness or toxic positivity. Instead, it is about “having a clear-eyed acknowledgement of all the challenges revision poses—and then taking them on anyway because our draft is worth it” (Hall, 2021, p. 43). Writers keep working on a draft because something in it compels them. Writers return, day after day, to the same words, believing that there is something there worth getting on paper. It has value, either for the writer or the world or both.

Chris’s chapter about transfer helped me understand better how to tap into the skills writers carry with them. As mentioned earlier, everything we write stands behind us when we pick up a pen or open our computers to write. Writers hold skills, sometimes forgotten ones, that just need a little nudging. Chris states that revision lessons are important, but transfer can happen when we enter a state of reflection. “In doing so [reflecting], we call forth a trove of mental resources—whether we’re drawing from minilessons we’ve been taught, books from favorite authors, techniques noticed in our peers’ writing, or self discoveries from our own previous pieces” (Hall, 2021, p. 136). Implied here is the criticality of time and space—to reflect, to think, to notice, to make connections. To challenge the current iteration of a piece of writing. To revise.

A last stance I’ll share is Chris’s chapter about risk-taking. Trying a new genre, writing about a personal experience, and letting go of paragraphs and sentences we’ve worked hard to craft are several risks all writers take. Whether it’s a leap to essay after composing nothing but fiction, writing into a traumatic experience, or cutting a gorgeous paragraph that contains poetic language that would make any writer seethe with envy, risk-taking supports a writer’s growth. Part of revision, as Chris states, is imagining a piece of writing as something different. Could this be something else? Would another structure or genre tell this story or convey this idea better? What we create is personal because for most of us, what we write comes from deep inside. However, Chris’s humanity radiates in this chapter. He reminds us that risk-taking is about growth, about taking a chance, about possibility. It isn’t a requirement, but risk-taking is a plunge into the unknown that more times than strengthens the piece of writing as well as the writer.

These three stances are the ones that continue to resonate even now. I’ve read and re-read chapters and sections, lingering in Chris’s words and knowing that the writers I work alongside will grow because of his incisive thinking.

I consider the homily I began this blog post with. While that experience continues to be embarrassing and frustrating, it is part of my journey as a writer. Could I have been more optimistic with my senior thesis? Absolutely. Could I have spent more time wrestling with paragraphs and ideas and writing to discover what I really wanted to say? Of course. But since I promised that I would not lament the past, here’s what I’m doing: I’m writing about it. I’m taking a risk. I’m remembering that we all carry stories inside us that shape who we are and make us beautifully human. And sometimes these stories need to come up for air. So we allow them to surface in the form of words. I’m not sure if any of this crossed Chris’s mind as he wrote, but he reminded me of the power of writing and what it means to take risks. I’m sure he’ll remind you, too.

But he reminded me of something else, too.

At the heart of our classrooms are our students. We ask a lot of them, especially when it comes to writing. I know I do. A writer’s workshop is a challenging place to sit—for kids and adults. For many, writing is a daunting task. But taking on a revision mindset gives us tools and strategies to break through roadblocks and fears. And to believe that we have something to say.

At the end of his book, Chris offers an invitation. It isn’t an invitation to adopt his book as a programmatic approach or a plea to implement everything he discusses. It is an invitation of inquiry: What do students need to grow their writing, their beliefs about writing, and how they perceive themselves as writers? By inquiring, we start a journey. And this journey engages us in thinking about our students and what they need to become stronger, more capable, more confident writers. They may enter institutions of higher learning, and if they do, they’ll need something to hold onto as they navigate college-level writing requirements. But beyond that, and more importantly, revision will sharpen their ability to communicate, to convey ideas and stories—either real or imagined—and to discover what they want to say and how they want to say it.

As we consider the students we work with and the rigorous yet beautiful world of writing and revision, I hope we remember its power. Right now, there are places where revision isn’t popular. Many teachers are expected to submit a year’s worth of lesson plans in the name of transparency. Yet all good teachers know that revision is critical. It’s critical in what we teach and model.

But revision is not just for writing or working with students.

It’s for all of us.

Revision challenges what is and encourages us to imagine possibility. I urge you to pick up your notebook or open a fresh document and write. I encourage you to wrestle with that piece of writing, to search for what you want to say, and find the courage to share your writing with your students. To identify the spaces in your teaching life where revision mindsets can set stagnation ablaze and illuminate all that is possible. It is here, as Chris says, that we revise our teaching, our writing, ourselves.

So, let’s start this journey together.

Let’s dance in the light of hope, joy, and possibility.

Our teaching will change, our writing will grow.

But above all else, we will, too.

Closing thought from #G2Great

We experience pure elation when we have the opportunity to read and share a book that inspires each of us and Chris Hall has definitely done that. Add to that the beautiful reflections that gifted writer Travis Crowder has so generously shared with us and you have a magical merger of inspiration. Thank you to Chris and Travis for sharing your gifts and passion for revision with our #G2great family

We will close with Chris Hall’s reflections. We asked him three questions to give us more insight on A Writer’s Mindset from his perspective.

What motivated you to write this book? What impact did you hope that it would have in the professional world?

Like most ELA teachers I know, I would groan when I heard my students say, “I like it the way it is,” about a draft of writing. I wanted to get to the heart of that revision resistance and figure out how to help students move past it, so I made it the focus of an action-research project. My language arts classes became a learning laboratory, where we tried—and continue to try—different approaches to create a culture of revision.

I hope teachers reading The Writer’s Mindset will find ways to make revision more authentic, engaging, meaningful, and joyful for their students. I hope the book helps educators see their writing instruction with fresh eyes—that it inspires them weave the stances of a writer’s mindset (metacognition, optimism, perspective-taking, flexible thinking, transfer, and risk-taking) into their existing workshop structures. Instead of just teaching revision as a series of craft moves or items on a checklist, I hope the book prompts educators to see how important mindset is for our student-writers—and how transformative it can be once we’ve started cultivating it.

Researching and creating The Writer’s Mindset sparked some subtle but seismic shifts in my teaching practice. I hope it does the same for educators reading it.

What are your BIG takeaways from your book that you hope teachers will embrace in their teaching practice?

Contrary to those ubiquitous writing process flowcharts, revision isn’t just a single step in the writing process. It’s not a stage after “drafting” and before “editing.” Revision is an awareness that’s present in every part of writing. When I observe my students at their best and most engaged—and when I consider my own experience as a writer—it’s clear that revision is happening throughout the writing process, not just after the end of the first draft. Writers stop periodically to review and re-read their words, making small and big adjustments along the way. They pause occasionally to notice what’s working and what feels off. They’re aware of the moves they’re making as they’re writing (their decisions) —and why they’re trying these (their intentions).

For this reason, it’s important to not wait until a draft is over to revise—we need to ask students to periodically reflect and revise during drafting, before their ideas start ossifying. We need to show them ways to be in a “process present”—to do quick metacognitive bursts throughout the life of a draft, not lengthy “process histories” after it’s over.

Another big takeaway is the importance of modeling our own writing process with our students. Each paragraph they write contains dozens of decisions, but our students aren’t always cognizant of them. Ask them, “What’s going well with your piece?” or “How’s it going with your draft?” and we often get a shrug. By sharing our own think-alouds with our drafts—our own messy, uncertain, unpolished drafts—we can take our internal writing voice and make it heard for our students. We can take all our unseen revision moves and make them visible. This helps students start to notice and name their own emerging revisions.

What is a message from the heart you would like for every teacher to keep in mind?

For our students—for all writers—even a little revision can feel like a lot.

As writing teachers, we want our students to embrace revision with zeal, but perhaps it’s enough that they appreciate it—that they feel, in the words of my student Molly, that “revision means hard work, but it’s worth it.” There are times we want our young writers to overhaul their drafts, but maybe it’s enough that they make a few modest but consequential changes.

Revision doesn’t have to be radical.

The same is true for you as an educator reading The Writer’s Mindset. All the stances and practices in the book aren’t intended as a recipe to follow or an outline to revamp your entire language arts program. Instead, it’s a smorgasbord to sample from and an invitation to shake a few things up.