#G2great is kicking off a five-part series on Weeding Misguided and Harmful Practices. The first in the series was Thursday, January 30, 2020 and we tackled the harmful practice of not providing adequate book access for all children.

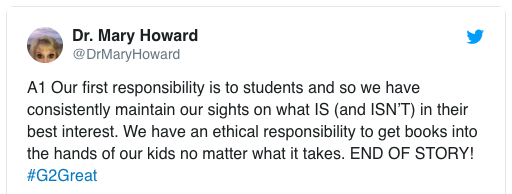

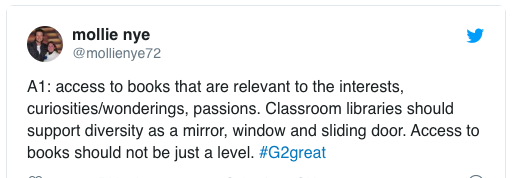

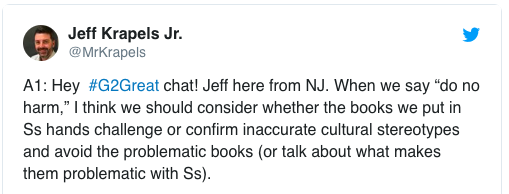

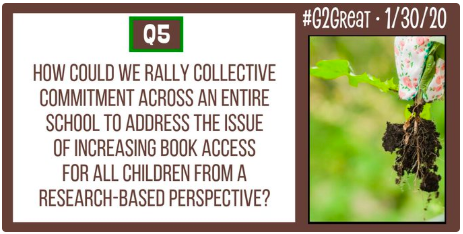

It may seem odd that we would feel the need to address this issue, but we must as many children in America live in what can be defined as book deserts. We, as educators, can positively impact this by a commitment to ensure that we provide books in individual classrooms, frequent campus libraries with our students, and encourage kids and their families to make visiting public libraries a priority. In short, we can and must advocate for books, and more books for every child.

Multiple studies have documented the impact of classroom libraries: there are more books in the classrooms of high-achieving schools, and more students who read frequently. As reading researcher Richard Allington put it, “If I were working in a high-poverty school and had to choose between spending $15,000 each year on more books for classrooms and libraries, or on one more [teaching assistant], I would opt for the books … Children from lower-income homes especially need rich and extensive collections of books in their school …”And they need actual books, not electronic devices that store books. Real books don’t require electricity or batteries. They survive rapid changes in technology and digital storage. –Nancy Atwell

As with exposure to vocabulary, access to books can have both immediate and longer-term impacts on a child’s academic and socioeconomic outcomes. Living in a book desert “may seriously constrain young children’s opportunities to come to school ‘ready to learn,’” Neuman and Moland write. A lack of access to books may help explain why, according to some research, children from economically disadvantaged communities score 60 percent lower on kindergarten-readiness tests that assess kids’ familiarity with knowledge as basic as sounds, colors, and numbers. And researchers say living in a book desert in one’s early years can have psychological ripple effects: “When there are no books, or when there are so few that choice is not an option, book reading becomes an occasion and not a routine,” they write.

–Where Books Are All But Nonexistent by Alia Wong (The Atlantic)

We know more books for more kids means that opportunities increase. Collectively, educators and those we enlist can make sure students have ready access to books they can and want to read.

Wherever we find ourselves working as educators, public or private schools, universities, or community work, we must work ourselves to increase book access. If you have not yet begun, take that first step to adding books to classrooms, school or public libraries. What ever form your activism takes, begin now.

Book access is critical for the development and growth of students as proficient readers who build and nurture their budding reader identity. It’s not a luxury for kids to be able to easily find books they can and want to read. It’s a necessity. And we can work to ensure that every child has access to books.

Join us later this week on 2.6.20 for Part Two in the series Weeding Harmful and Misguided Practice: Behavior Management.

One thought on “Weeding Misguided and Harmful Practices: Access to Books (First in the Series)”

Comments are closed.