by Mary Howard

Your grateful #G2Great co-moderators (Fran, Jenn, Amy and me) are so inspired by the dedicated educators who flash onto our Twitter screen each Thursday at 8:30 EST to engage in passionate warp speed dialogue. You get to experience the joyful conversations we support and celebrate each week, but what you don’t see is the joyful behind the scenes planning that grows into those conversations within a community of #G2Great learners. The four of us gather from across the map to ponder topics worthy of your gracious gift of one hour. Our ideas reflect a professional itch we can’t wait to scratch in the company of amazing educators. Some rise from our own curiosities while others rise from the thinking you’ve inspired us to bring to life on the screen. Our dedicated curiosity-inspired itch scratching sessions reflect the ultimate passionate planning we happily do in your honor.

Our #G2Great chat on 1/15/18, Celebrating Our Learners through a Success Lens: Losing the Labels that Blind Us, was an itch we couldn’t wait to scratch. This topic has come up on several occasions across most of our #G2Great chats and it’s a conversation that I have personally celebrated with Molly Ness, Brent Gilson and my own facebook page.

Any educator would be hard pressed to question the critical importance of putting the topic of labeling on the chopping block discussion table. I am certain that our #G2Great family would agree that it is our responsibility and honor to celebrate each child we are fortunate to have in our professional care. But the only way that we can do this is to truly see the child. If labels are all we see, our vision field is narrowed and will blur our view of the amazing filled-with-potential children in front of us.

Since this topic is particularly near and dear to my heart, this week I’d like to share my personal reflections inspired by our chat using three questions and then share inspired tweets at the end of my post.

What are some of the labels that blind us?

Labels have been a part of the educational universe since I began teaching in a special education classroom in small town Missouri in 1972. Labels come in every shape, size, color, nationality and personality and can be both legitimate terms that could potentially inform (not dictate) instruction when viewed flexibly or simply perceived and ill-conceived. There are far too many labels to mention but I think of them as falling into five categories including Diagnosis-Based that range from medical, psychological, cognitive, and physical diagnoses to grossly unqualified individuals diagnosing without benefit of diagnostic qualifications: autistic, ADHD, handicapped, OCD dyslexic, mentally retarded, depression, gifted; Assessment-Based: test, score, level, lexile, grade (or any number that can be charted on a color-coded spreadsheet); Setting-Based: tier, resource, special education, Title 1, remedial, intervention; Class-Based: poverty, race, parental education, financial position; or the very dangerous Descriptor-based: behavior problem, struggling, noisy, hyper, slow, shy, introvert, extrovert, bully, lazy, cry baby, stubborn, pig-headed, troubled, trouble maker, scatterbrained, handicapped (the most dangerous and degrading list of all because all it takes is a slip of the tongue or prejudicial designation). The terms listed above are only a small sampling of those that are pervasive in our schools. I’m quite certain that if you added to this list, it would double or triple. The one thing they all have in common is that when using any label to define children, we risk blurring the lines between what we know about that child and what is professionally useful. Any term that forces us to turn a blind eye to who this child truly is as a human and learner beneath what we see on the surface will become a label that can last lifetime.

What is the potential impact of these labels?

The potential impact of these labels is immense and can quickly spread like a virus across a building. There is a real danger for labels to formulate and perpetuate the myth that children are in some way flawed – thus leading to flawed thinking that could translate into flawed practices. While a diagnosis from qualified professionals may represent legitimately useful information if viewed in a flexible and open-minded way that draws from other sources of information, there is also a risk for the gross misrepresentation that will alter our view of children. Even a legitimate diagnostic terms can be misinterpreted when viewed narrowly. For example, ten children diagnosed with ADHD or dyslexia will reflect ten different sets of needs since there is no one-size-fits-all diagnosis or solution. This means that we have a responsibility to know the child beyond the diagnosis so that we can explore the most appropriate and timely instructional goals based on the needs of this child rather simply a term of any kind. As a past special education teacher, I was obligated to identify descriptors from a pre-determined list that would then give me computerized goals that were not helpful until I could mentally add may own knowledge about my students into the mix. Sadly, this approach is still prevalent with or without the use of computers in the form of narrow grab-and-go goals that are usually far removed from the child. Legitimate or not, any term must be used in professionally responsive ways since hyper focusing on any term while excluding our understandings about children will muddy the instructional waters and cause us to lose sight of the child. I’m even more concerned about the other categories since they often reflect irresponsible labels educators apply to children without benefit of seeing the child beneath the surface, meaning that behaviors can cause emotional reactions to the behavior itself without any attempt to uncover what that behavior could be telling us about this child. Quite frankly, far too many of the labels I placed on this list are mean-spirited and laden with questionable knowledge or personal biases that have little to do with unique learners that fill our classrooms. Sadly, they can also reflect personal preferences so that a teacher who likes a quiet classroom is more likely to label a child as noisy or disruptive rather than to attempt understand the child or even question our own belief systems.

How do we counteract labels to keep children at the center?

This is certainly the ultimate question we should all be asking across an entire school. In order to counteract labels, we must take the culture of the building into account and build a bridge between the labels that diminish our efforts and the student-centered perspectives that will allow us to view our children in a celebratory rather than critical way. We can begin this shift by thinking in terms of three steps: perception, collaboration, application.

PERCEPTION

Our first step is to increase our own awareness that these terms are often used when we don’t even realize it. We have become so immune to saying or hearing label-inducing language that we may not even recognize that it exists all around us and is far more widespread than we are willing to acknowledge. What if we took it upon ourselves to come together as a school so that we can listen for and capture labeling language that is filling the learning air poisoning our thinking from one side of a building to the next. Considering how quickly these terms can morph into label that limit our view of children, this would be a worthy use of time. Imagine if we gathered terms that are actually being used personally and by others and then listed them for all to see. The goal isn’t to point a finger of blame since we are all guilty of doing this without a second thought. Rather, our goal is to turn the process of creating a visible list into a reflective process. Even better, we could ask teachers to make a personal list of the terms that creep into their own language and add them to the chart anonymously. A concrete visual reference would increase our awareness and lead to meaningful conversations about how we can view our children in more purposeful and productive ways. We can’t tackle the issue of labeling until we acknowledge that it’s an issue in the first place. I suspect that every school might be astonished just how quickly this list grows.

COLLABORATION

Once we put a zoom lens on the labels we use without thinking, then we need to consider how we will change the way we think about children. To change our culture and avoid the labels that travel with kids indefinitely and lead to a THAT child mentality, we must alter the kind of dialogue we are having about children so that we can literally change the face of those conversations. When I sit in on a team meeting or talk with teachers to explore their instructional goals and practices, I have to ensure that these terms don’t thwart our efforts to keep our sights on the child. One of the first things we can do to accomplish this is to ensure that we are keeping this child in our discussion in a very concrete way. If we placed a photograph of that child in clear view, we would be more cognizant that we are not talking about a number, descriptor or score but a living breathing child who depends on us to keep our conversations grounded. A visible photograph will offer a visible reminder to keep our discussions rooted in what we actually know about that child rather than what we think based on an opinion or a number that rarely reflects the real picture. We can enrich this process by using the child’s name frequently along with specific now noticings that can lead to next step actions. Respectful conversations move us from labels to understanding. To extend this, I ask teachers to use a strengths-based approach by naming three things the child can do before offering even one need. This is an important shift in our thinking because strengths keep our sights on what is amazing about this child at this moment in time and become a stepping stone to next step goals. When this collaborative process moves us from deficit discourse to success discourse, it ultimately becomes a way of thinking that is worth spreading across our building.

APPLICATION

One of the most important ways that we can counteract these labels is to consider how our decision-making can exacerbate the very things that may have led us to those labels in the first place. This step allows us to hold up a reflective mirror and turn our own thinking inward to consider whether what we do sets up roadblocks to students’ success so that we can relinquish anything that is bringing labels to life in our own minds. We can begin by letting go of the defective notion that one-size-fits-all instruction is a common sense proposition since we do not have one-size-fits-all children. If we could step back from programs, packages and scripts that derail us and flip the word fidelity from publishers to children, I suspect that most of the things we see that lead to labels would begin to dissipate from view. If we omitted computerized tasks that attempt very poorly to do the work only a knowledgeable teacher can do then labels would begin to dissipate from view. If we made student choice a priority across every learning day then labels would begin to dissipate from view. If we created joyful learning experiences that revolve around beautiful books reflective of our children then labels would begin to dissipate from view. If we got rid of level charts, classroom library leveled bins, Accelerated Reader scores, clip up charts and every questionable approach that does little more than beg for the designations of haves and have nots then labels would begin to dissipate from view. This reflective mirror turned inwards forces us to take a long hard look at our own practices so we can question what we do, why we do it and how it impacts children in positive or negative ways. Once we do this, we can then reflect on how to invest our precious time and energy where it matters most – crafting learning opportunities filled with high expectations within a learning environment that celebrates meaningful authentic reading, writing and talking. Combine this purposeful use of time with open-ended flexible experiences and we demonstrate that we embrace the children we have rather than the children we wish we had. In short, we could alleviate the labels that set up instructional roadblocks by assuming professional responsibility for our own professional decision-making so that we can redesign learning environments where every child can and will thrive because we chose to make that our first priority.

In closing, we must be more intentional in our efforts to lose the labels and create a culture of deep respect for our children. I believe that these three questions could be the starting point to that end. At #G2Great, we take labels that blind us to the remarkable children in front of us very seriously. At a time when levels, tests, scores, grades and numbers have come to rule our lives, it is more important than ever that we are aware of the labels that diminish our efforts so that we can open the door to conversations that will lift us to the highest heights of amazing. In her exquisite new book, Literacy Essentials, Regie Routman states:

Instead of thinking, “What’s wrong with the learner?” let’s ask, “What might I offer or do differently to ensure the students is successful?” Sometimes it just takes some compassion, honest, but kind feedback and easy-to-implement ideas to get students started.

We have a professional responsibility to children and a moral obligation to lose those labels in their honor. In the words of Kylene Beers, A Kid is Not an “H.” Perhaps we can also agree that a kid is not a diagnosis, assessment, setting, class or descriptor. Any label that is used to define children will blind us to the remarkable child we can only see when we celebrate them in all their bountiful glory from every possible angle.

Look closely my friends and we just might be surprised by the beauty we see when we do!

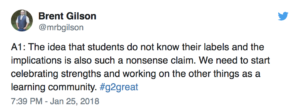

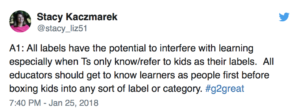

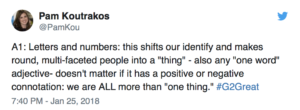

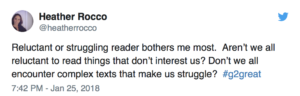

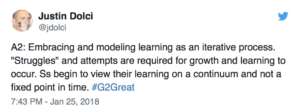

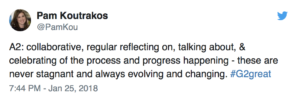

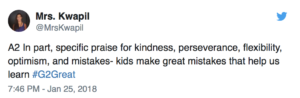

Some of inspired #G2Great Tweets