by Mary Howard

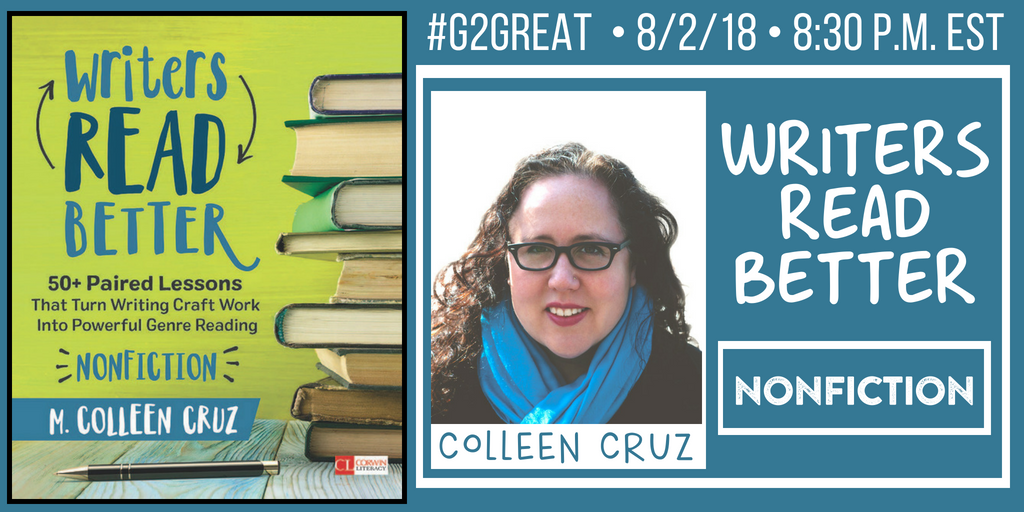

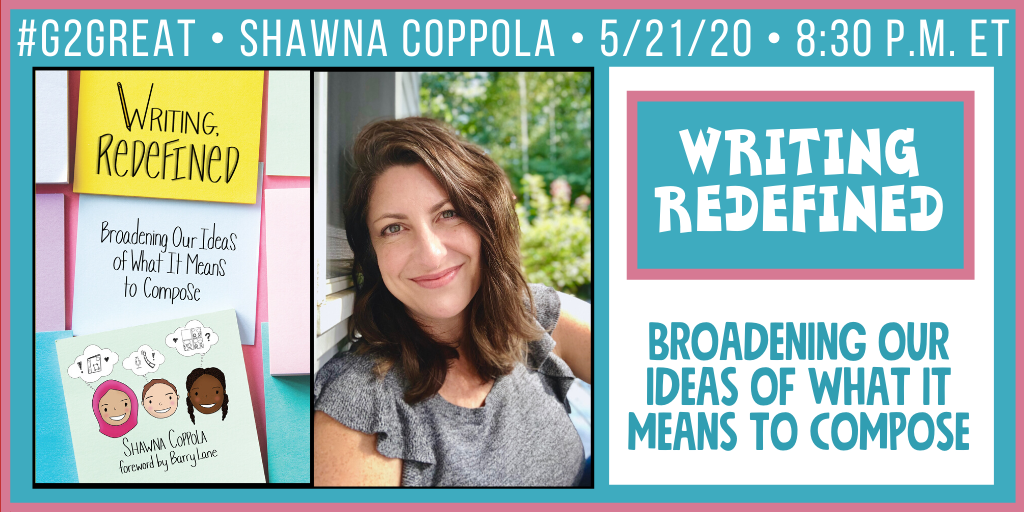

We have really been looking forward to welcoming Shawna Coppola as our first-time chat guest host. #G2great is grounded in the belief that our professional understandings are in a perpetual state of growth –– a continuous flux of re-envisioning, revising and refining what we now know so that we can explore the possibility of what is as yet unknown. We love that Shawna beautifully captures the spirit of this deep-rooted belief in the title of her book: Writing, Redefined: Broadening Our Ideas of What it Means to Compose (2020, Stenhouse).

Before I began this post, I paused to ponder what the key related words, redefine and broaden, mean to this ongoing process. The synonyms below felt deserving of a word cloud.

I’m struck by the placement of the two key words above sandwiched in the center since it happened by chance. It’s a perfect complement for a process of redefining according to Webster’s dictionary: to reformulate, reexamine or reevaluate especially with a view to change or transform. The combined meaning of these words with a focus on change or transform our thinking assumes action. This inspired me to read Shawna’s book in the hope that it would redefine and broaden my understandings about writing. I was not disappointed.

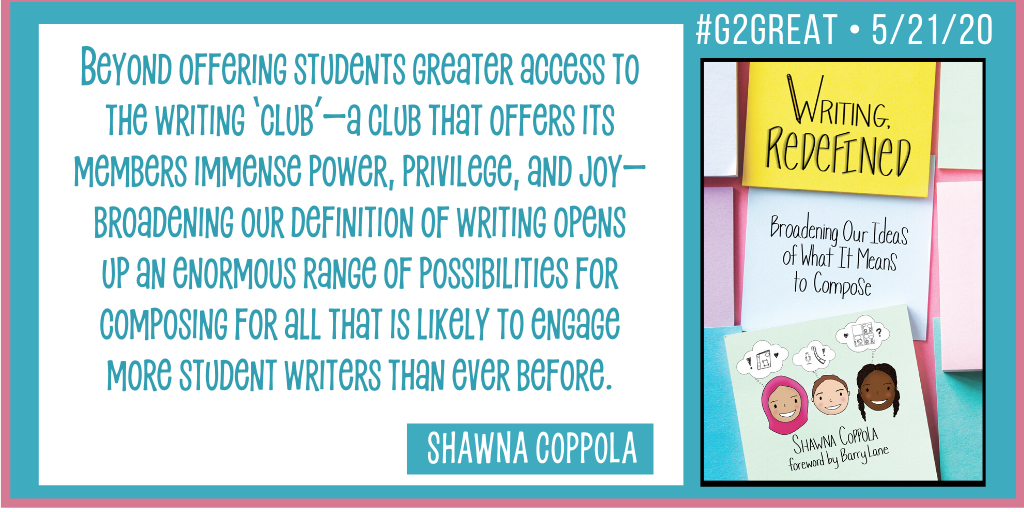

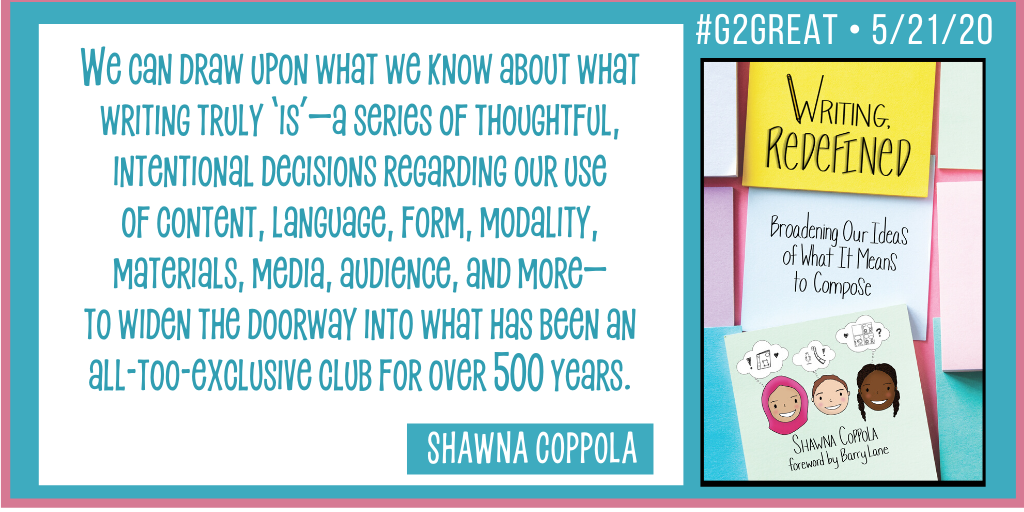

Starting with the cover, Shawna invites us to redefine what should count as writing so that we may broaden our perspective. With transformation in mind, she poses a critical question in chapter 1: Why “Redefine” Writing? On page 2, I felt like I’d found the heart and soul of Writing Redefined that instantly became the WHY of this post:

Of the students you have known over the years––both those you’ve taught and those you’ve learned alongside––who among them have been granted access into the “writing club”?

Shawna defines membership to the writing club as those who self-identify as writers or have been identified as writers by others. As someone who came to a sense of access to the writing club very late in life with lingering feelings of membership that still wavers now and then, I was captivated by this challenge. I am grateful for Shawna’s wisdom for the transformative thinking that can swing the door ever wider to welcome all children (and their teachers) into the writing club. Shawna’s response to the first of three questions seems like a good starting point to redefine and broaden our view from her wise eyes:

What motivated you to write this book? What impact did you hope that it would have in the professional world?

Seven or eight years ago I began to notice via my social media feeds how much more frequently my friends, family, colleagues, and acquaintances were using visual text to, in essence, share the stories of their lives. At the same time, while working as a literacy specialist in a K-6 school, it became so apparent to me how quickly the ways in which we encourage our student writers to compose visually “dropped off” the older they got and the further they moved through the grades. This seemed so out of touch with what was happening outside of school spaces! I began to dig into the decisions our younger students made as writers, even when they were composing visually (e.g., for a picture book), and I realized that almost all of the decisions we make as writers, with the exception of modal decisions, were the same regardless of the mode we used. For example, we make decisions around content, audience, genre, organization, even motor planning whether we are composing a literary essay or a wordless picture book. I was lucky enough to work with colleagues who were willing to co-teach writing alongside me in a way that broadened the forms and the modes of composition that have been traditionally privileged in schools. When I saw how both students and my colleagues responded to this, I could not help but want to bring what we had learned–what our students had taught us about composition–to a larger audience.

What strikes me about Shawna’s response is her commitment to use her noticings about writing happening outside of school and concern for the dwindling writing happening in schools as a call to action. This was the launching point for an exploration of the ideas that would BROADEN “the forms and the modes of composition traditionally privileged in schools.” Inspired by her own wonderings, she shares across the pages that follow the HOW and WHAT to accomplish her lofty but very achievable WHY.

Shawna’s book quote further illustrates this idea of “access to the writing club.” My curiosity about why I did not feel early access when Shawna and others do, motivated me to contemplate how we can ensure that this is not the case for the children who enter our classrooms now and in the future.

Turning to Twitter as a Lens for Writing Redefined

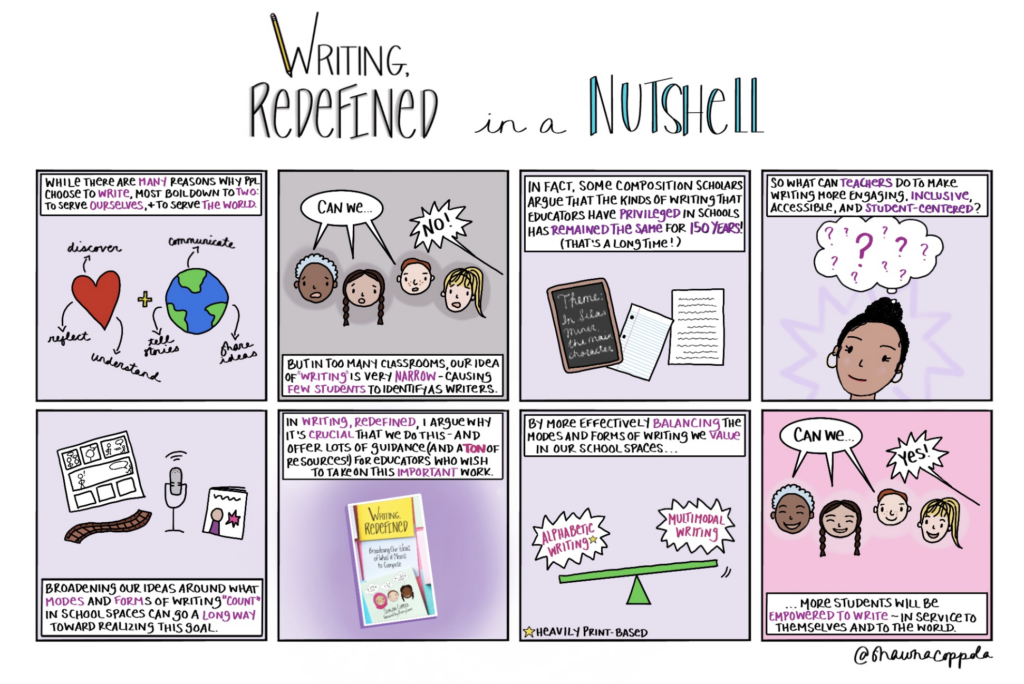

For the sake of this post and to satisfy my curiosity about this writing club access, I decided to turn to our #G2Great chat to peruse Shawna’s twitter style wisdom on this topic. Very early in the chat, Shawna shared the comic she wrote to summarize her book:

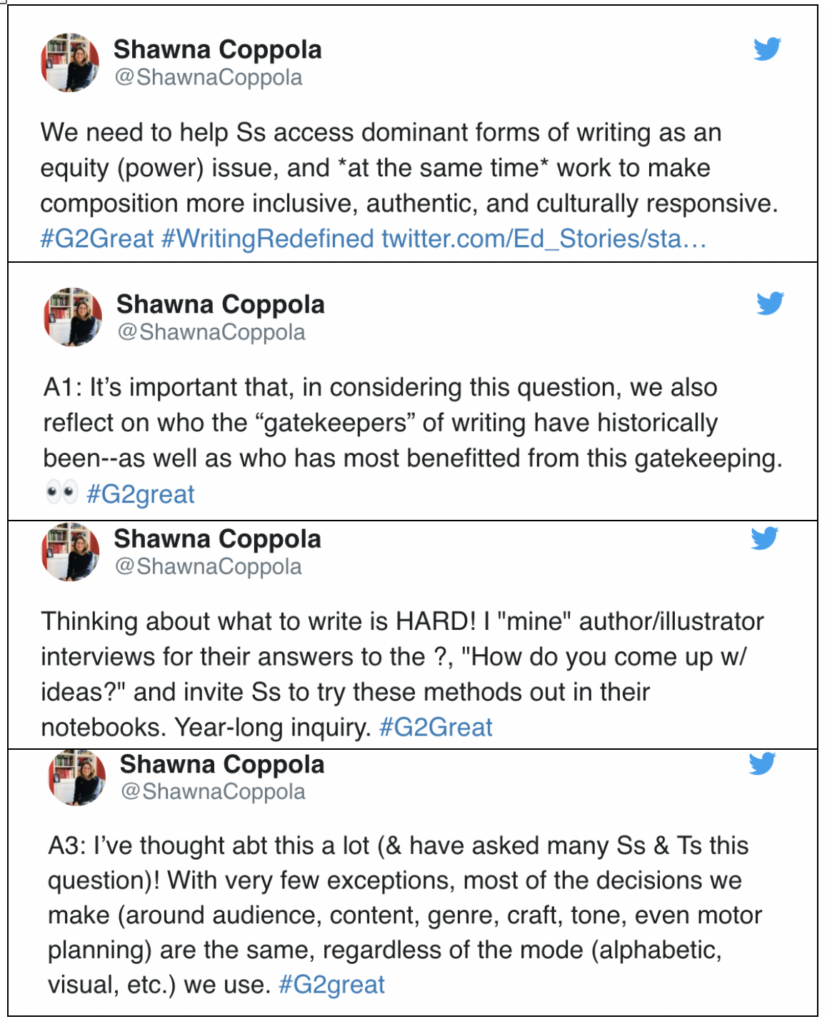

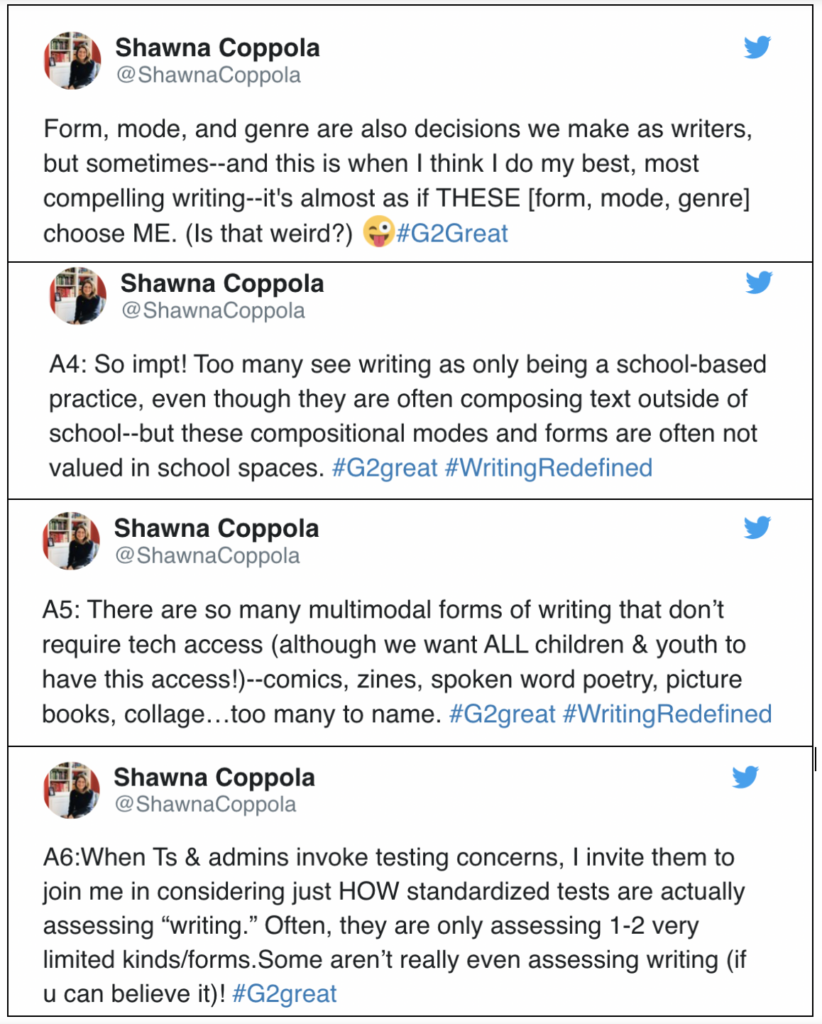

Shawna’s tweets further illustrate a starting point to REDEFINE writing

With this wonderful advice guiding our way, I’d like to return to Shawna’s second question that adds insight to this invitational process:

What are your BIG takeaways from your book that you hope teachers will embrace in their teaching practices?

• That the compositional practices we have privileged in school spaces has been far too limiting for far too long (and many composition scholars have been arguing this for literally decades)

• That when we limit what “counts” as writing in school spaces, far too many students are left out–and are left unengaged

• 3) opening our minds and hearts to a wider variety of forms and modes of composition––all of which exist outside of school spaces!––can make writing more authentic, more joyful, and more inclusive.

My Final Thoughts

As I look back to where I began this post, I once again return to the idea of granting all children access to the writing club so that no student is ‘left out or unengaged.’ I am struck by Shawna’s last words in the question above that should inspire us all to take next steps to redefine and broaden our view of writing:

“…opening our minds and hearts to a wider variety of forms and modes of composition––all of which exist outside of school spaces!––can make writing more authentic, more joyful, and more inclusive.”

We are grateful to Shawna Coppola for opening our minds and hearts through her book and generous sharing with our #G2Great family. She inspires and informs our efforts to redefine and subsequently broaden what it means to compose as we ensure that all children will have access to the opportunities that will welcome them as members of the writing club, not just in school but long after they leave our classrooms and venture out into the world where a much bigger writing club is awaiting them.

And so, I close with Shawna’s response to the final question followed by a quote from her book that brings my fascination with granting access to the writing club full circle:

What is a message from the heart you would like for every teacher to keep in mind?

That the best way to develop our pedagogical practice as teachers of student writers (but really, as teachers of anyone!) is to build a habit of noticing what kids CAN do. What can they do as writers, and what do they know, that will help us determine what they are “ready for” next? I promise folks that once you build this habit of using an asset lens to see the many gifts our student writers can offer, the more joyful and effective your practice as an educator will be.

And Shawna’s book wisdom:

Thank you for helping our #G2great family see those many gifts, Shawna!

SHAWNA COPPOLA LINKS

Preview and study guide for Writing, Redefined:

Voices from the Middle piece by Shawna Coppola: Writing, Redefined

MiddleWeb piece by Shawna Coppola: Our Students Need a New Definition of Writing

Infographic piece by Shawna Coppola Writing: Genre, Forms and Modes (Oh My!)

#TheEdCollabGathering presentation with Shawna Coppola and Dr. Tracey Flores: Somos Escritores: “Redefining” Writing for Great Inclusion, Authenticity and Engagement