by Mary Howard

December 6, 2018. That was the day that Cornelius Minor graced our #G2Great family and touched all who were part of the experience. Cornelius had previously shared the #G2Great stage with Courtney Kinney in Brilliant Tapestries: Building Classrooms that Reflect the Lives of the Children Who Inhabit Them. This time, it was Cornelius’ powerful new book that inspired passion-fueled dialogue: We Got This. Equity, Access, and the Quest to Be Who Our Students Need Us to Be. Heinemann 2018

I was honored for the opportunity to write our post this week so I dug into this beautiful book with great fervor to prepare. But as I read, I began to worry that I couldn’t possibly capture his brilliant cover to cover thinking. I realized that the only person who could do this post justice was the person who penned those mesmerizing words in the first place. Luckily, Cornelius graciously agreed to an interview and in typical Mary style, I excitedly crafted eleven interview questions and emailed them to him.

On a quiet early Saturday morning from my hotel room in Phoenix Arizona, I joined Cornelius in Google Hangout. I was instantly enraptured listening to his words and the sounds of his children playing in the background. As soon as I asked my first question and listened intently to heartfelt honesty, I realized that his words could take center stage and that the questions would simply follow his lead. And so here are the words verbatim that reduced me to tears within minutes on a lovely early morning interview I will forever hold dear.

As I read Kwame Alexander’s beautiful foreword for your book, I felt transported back in time to the annual International Literacy Association (ILA) Conference two years ago when you led a quiet room filled with love and hope. I can’t help but wonder if a seed for this book was planted that day. How did that experience impact you in writing this book?

CORNELIUS

I think it was the seed actually germinating. The seed has been planted forever. Like I’ve always been this guy. One could argue that I’ve inherited a lot of this work from my ancestors. So really the seed was planted when the first African was brought in chains to the United States. The seed was planted when we decided that we wouldn’t give women equal pay. The seed was planted when we decided that immigrants weren’t equal to people who were born here whatever that means. The seed was planted when colonists killed the first Native American. So the seeds have been around and I am lucky enough to have inherited lots of good mentors and a lot of people have trusted me with their work. And so that room I think was me already holding the seed that so many people have given me and me being not afraid to let it grow in public.

I don’t know if you felt it, but those of us sitting in that room were soaking in all of that from you. That was a magical experience and I recall thinking in that moment how much we needed a book from you because of what you offered that room. You may not have noticed the faces as we looked around the room but they were filled with hope and love. So where did that idea of hope and love fit into this in your mind?

CORNELIUS

One of the things that I hold onto and that I’m very clear about is that hope is not a strategy. The people who are organizing against us are not hoping. They are erecting programs and policies and fundraising. I think one of the greatest tragedies is that when the good guys get together, they just tell us to hope. And so rather for me the word hope is a characteristic. Hope and love are characteristics that I want to hold on to while I’m working. But I think it’s really important, and I say it almost everywhere I go. People ask me if I’m hopeful. I am pragmatically optimistic but I do hold on to hope and love as characteristics of my work but that it must be work. The notion that we go around society telling people to hope while bad people are allowed to organize and plan just doesn’t feel right to me. And so, I always want hope to be the defining feature. I always want love to be the defining feature. When people work with Cornelius they’re like “Wow, that work, that progress that we made together felt very hopeful.” But hope alone cannot be the entirety of our work. I think that’s how the bad guys keep winning. We’ve been duped into thinking that hope and love are the entirety of our work – and they are not.

Do you feel like we’re moving in that direction in education or in the world?

CORNELIUS

You know, Mary, that’s a really tough question for me right now. Just mainly because what this book has done is that I invite all of the hard places. So, you call Cornelius when someone spray paints a swastika on the wall. You call Cornelius when there’s been a hate crime. You call Cornelius when some kid uses the N-word and offends a whole community of people. Lately I see the hardest things. I just got called by a mayor of a town and I was there last week leading a community session. Someone had spray painted racist graffiti all over the school. There had been death threats. There had been a school shooing. I mean there was all kinds of stuff. That’s where I get called into now so I see the hardest of the hard. It’s not just the literacy work. Well, it’s interesting because to me it’s all literacy work. After a hard incident, like after a school shooting or after some big graffiti goes out, it’s really easy to say, “Oh let’s all love each other.” And then we’ll get on the news and we’ll play some nice music and then we wait two weeks and we think that it’s over. But what happens is if we don’t communicate, if we don’t talk about it, these things happen again and again. Like we just hide them behind sayings or euphemisms or whatever. I always tell people that if you sweep mold under the carpet, it just grows. So, if something happens, what we do is love each other and we don’t confront the thing that happened. Then the next time that thing happens it’s going to be three times as big. That’s been my work for the last year and a half. So I do see things changing in that people are willing to talk about them, but I’m ready now to move beyond talk and move into true community engagement. And that’s much of the work that I’m leading. That’s what I was doing last week so when you engage a community, it’s really ugly because you’ve got to say, “Well here’s our truth. Here’s what happened. Here’s how we feel.” And we’ve got to create a space for people to feel. Again, I was in town last week when there was a death threat that had been made and somebody had spray painted on the bathroom wall of the school that they were going to kill all N-words on Monday so they were specific. Parents did not want to send their kids to school on Monday because this was a very credible and articulated threat. And so we had to think about how we were going to do community outreach to those parents who were most impacted. What does outreach look like to black parents vs. outreach to white parents? What does outreach look like to our Jewish parents? And then we have to do that work. We got to get on the phones. We got to call people and let them know that you’re safe here and we care about you. And then there are people who don’t want us to do that work. There are people who are like “You shouldn’t call and everybody should just come to school because it’s okay and why are those people afraid? It’s just spray paint”. And so there’s all of that. I think what happens is that the real work is not beautiful. I’m really trying to lead people through that muck in a way that is defined by hope or in a way that is characterized by love. And so I think these last few months for me have been spent not shying away from the ugly and not afraid to talk about the ugly and that’s really hard for educators. As educators we tend to want to deal in the sunny side of things, but much of our work ain’t sunny. And so how do I lead people into that work in a way that is characterized by hope and by love? That has been the question I’ve been asking myself and to be honest, Mary, I don’t know. In every town it’s a new thing. I think it is changing, but in the way that things get worse before they get better. So, a wound has to scar before it heals and right now I think we’re in the really ugly scar and it’s going to be here for a while.

Did you realize that your work was going to lead you in this direction? It sounds like this is all of the things that you’ve spent your life becoming. But did you know that you would someday start doing this important work beyond the school arena?

CORNELIUS

Well it’s kind of funny again, Mary, because it’s always been my work. One of the things I did for Heinemann is I sent them news clippings of my teenage years. This has been me for twenty-five years, You know, I’ve been doing this stuff since I was fifteen. I have a larger platform now which is like great. It’s really really exciting. But when I think about the work that I’ve always done in my hometown or when I think about the stuff that has mattered to me, it’s always been my work in a very small way. When I was fifteen, I protested my student government and I took it over and became the new president. It was like a minor coup. Then when I was eighteen I was protesting the governor and by eighteen I had spent the evening in Governor Bush’s office in Florida because I was against his policies for schools. It’s kind of been an interesting year for me. I don’t know if I told you a college roommate of mine was running for governor of Florida so it’s been an interesting year for both of us. These are people I’ve been growing up with my entire life and now that we’re forty or forty-one, the work that we’ve been doing forever is now catching the attention of people outside our communities. I didn’t know that this book would do this thing because what’s fascinating is that when you’re in the literacy world, it’s really hard to find out where you fit in. I’ve spent my last eight years with Lucy doing very disciplinary literacy and then on the side being Cornelius but in a very interesting way of doing this disciplinary work. What the book has done is effectively merge the two. That people are starting to see, and I think that people are ready to see, that disciplinary literacy has to be inclusive. That disciplinary literacy has to address nationality and race and class and gender and ability. And that’s really exciting to me. There was a time, and I even remember there were people who I love in this field, who would tell me that my work had no place in teaching. And these are people that I love. And I think it was because we didn’t have the language for it. In many ways when you’re not from a marginalized group you don’t see these things. And so I have always felt the impact of my immigrant-ness on school. I have always felt the impact of my blackness on school. I have always felt those things. But then you work in these overwhelmingly white spaces and people say race doesn’t matter here or gender doesn’t matter here and you’re like, “No it does because I’m here and I’m feeling it.” And it’s unfortunate because we think about things like our current president and I think what our current president has done has made visible all the things that marginalized people have been talking about for two generations. And it’s made it visible to everybody else. And to me that’s a crisis of literacy because people have been communicating these messages for generations but largely people haven’t been listening. Then we think about the language arts; reading writing speaking and listening. So what does it mean that we have a Shirley Chisolm that says, “This was a problem two a generations ago but nobody believes it until Trump shows up.” What does it mean that we have a Carter G Woodson who wrote the book The Mis-Education of the Negro who named this four generations ago but then nobody believes it until Betsy DeVos shows up. And to me that’s a crisis of literacy that people have been speaking – women, people of color, immigrants – but nobody has been listening. That’s a language arts problem.

Note: At this point Cornelius moved me to tears

“I’m imagining you standing in front of that classroom just like in that room at NCTE and I think that the real power is not just what you say but the way that you say it and the way that you move people. Thank you for moving me this morning.”

CORNELIUS

But it’s all of us and I think that everybody feels this way. One of the things I’m learning as a father is that you have permission to be sad and that you have permission to be excited or disappointed. We try to police kids’ emotions all the time. When my daughter gets sad I have to remember that she’s a human and that the thing that made her sad exists and she has permission to be sad. I think that as adults we’ve inherited this mindset that I don’t have permission to feel how I feel. I have a good job. I’m a teacher. I’m a leader in my community. I should not feel sad or I should not feel frustrated because I’m an adult. I think one of the things is that I hope to achieve with my work – and it goes back to that defining quality of hope and love – is that as adults I want to extend the same grace to you as an adult that I extend to my children. That when I listen to my children speak they have permission to be sad and when I listen to Mary speak, she has permission to be frustrated or sad or angry or not know the answer. And we don’t extend that grace to each other and I think that’s what I want my work to do. That I have permission to be imperfect and so do you.

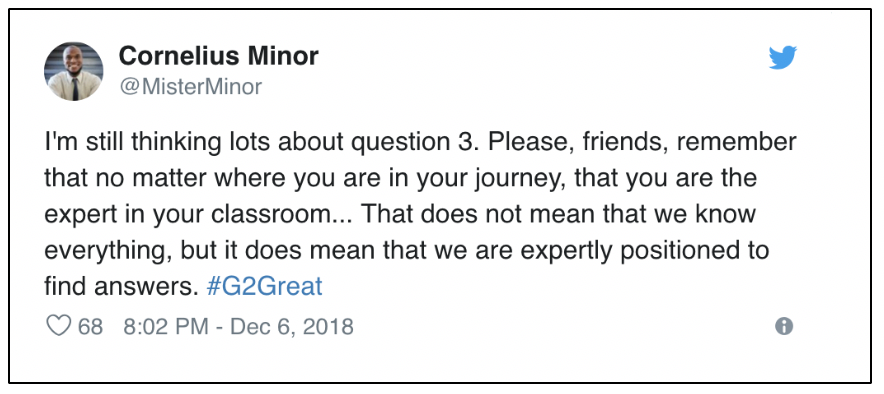

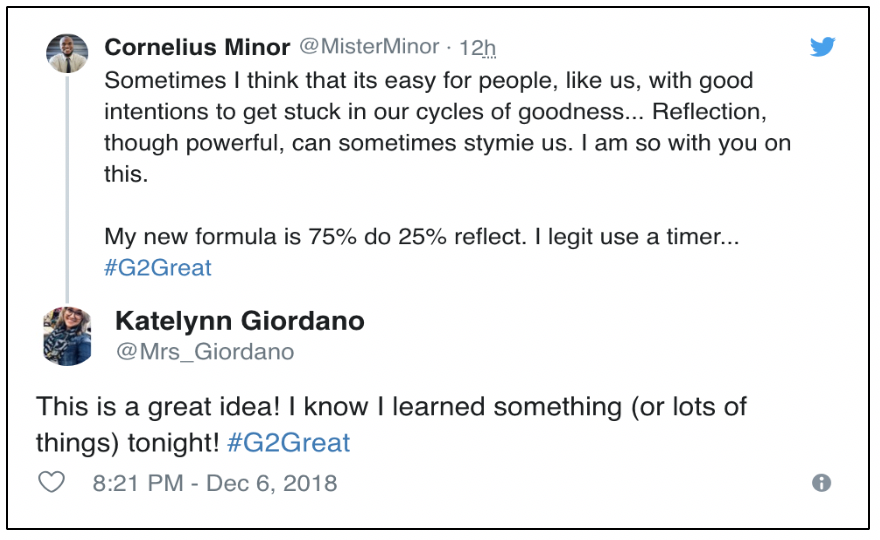

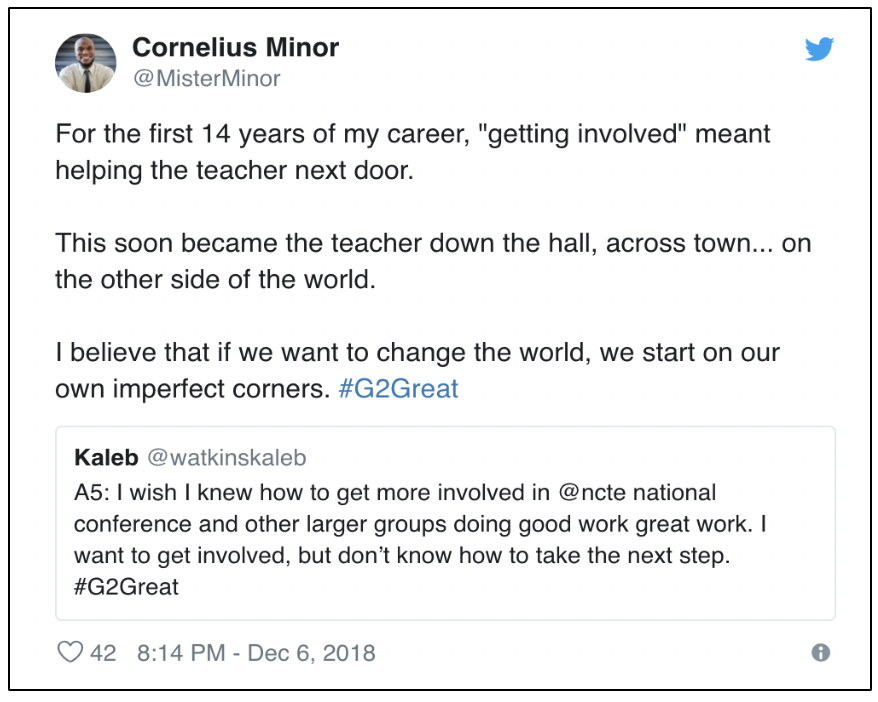

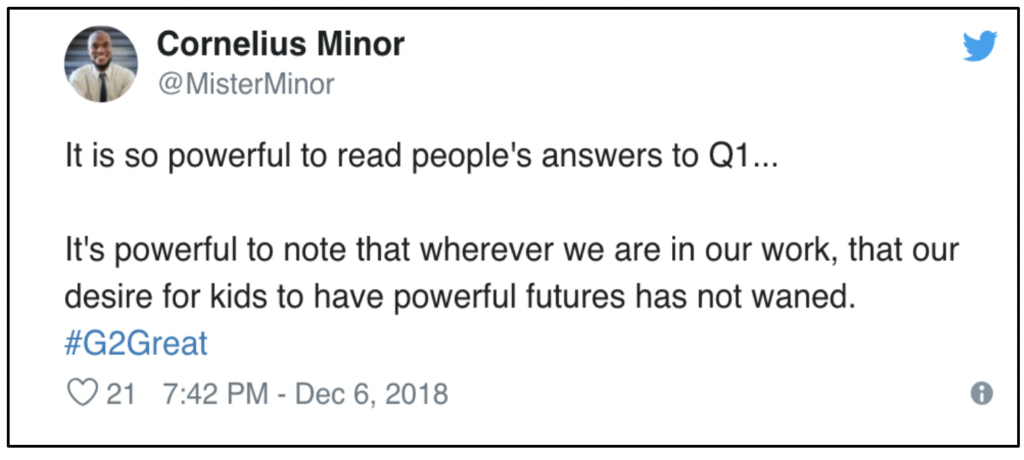

I think you modeled that on the chat Cornelius. I went through and captured all of your tweets and what was amazing is that people would say something and you would respond to them with the message that it’s okay to feel that way. I think that people don’t feel like it’s okay to feel things like self-doubt or all the other things that we all struggle with. That was really amazing.

From the opening words to the closing, I got a sense that this book is YOUR heart on paper and I’m feeling like that’s true listening to you now. What “heart message’ did you hope this book would spread across the universe?

CORNELIUS

It’s complicated and I think that there’s several. One is that it’s bigger than education. Two is that even though it’s so big, we can do it. I know this sounds silly but I was like “Book?” I want them to be able to read the title that we can do it. We Got This. It’s a big message that I wanted for people. Like how can a person browsing the book store or surfing the internet who doesn’t read a single word of the book but just reads the cover leave being a better practitioner? So that’s the message, that we got this, that you are enough and I think that there’s so much in teaching that makes us feel like we’re not enough. And we are. We are. I don’t know how people have gotten to the heart of teachers and made them feel like they can’t do things. And it’s in every setting. Yesterday I was in a school. Many of the kids who were separated at the border from their parents were relocated to New York City. They have incredible trauma, incredible journeys. These people are leaving Central America and Mexico and attempting to find opportunity here and our government sends them away. These teachers are doing such important work in these schools and they are amazing. I’m just the guy who shows up and says nice things but 100% of that work is those teachers showing up every day and doing the work. But even the people who are doing the best work in the world have been made to feel like they’re not enough. So yeah, you asked me about the heart message of the book and it’s really that “You are enough.”

You mentioned the title and I’ve been wondering if there is a reason for the period at the end of We Got This. That really connected with me so is there a meaning to that?

CORNELIUS

Oh yes. That was actually one of the biggest debates in all of the writing of this book. Was it going to be a period? Was it going to be an exclamation point? Was it going to be nothing at all? My designer, Monica, actually became in very many ways a co-writer. The book is so visual that I really wanted the design to kind of make a point and I needed somebody who really understood what I was trying to do. Monica actually invented that period because it’s a definitive “IT IS.” To say We Got This [exclamation] suggests that we don’t always have it. To say We Got This [period] says that even in our imperfection we’ve got it indefinitely. And so I think that period is really important there.

There are so many challenges in education these days and so many things teachers are facing through no fault of their own. Where do we even begin? How do we refuse to allow the challenges to thwart us and still be inspired to lift ourselves up to do what we need to do?

CORNELIUS

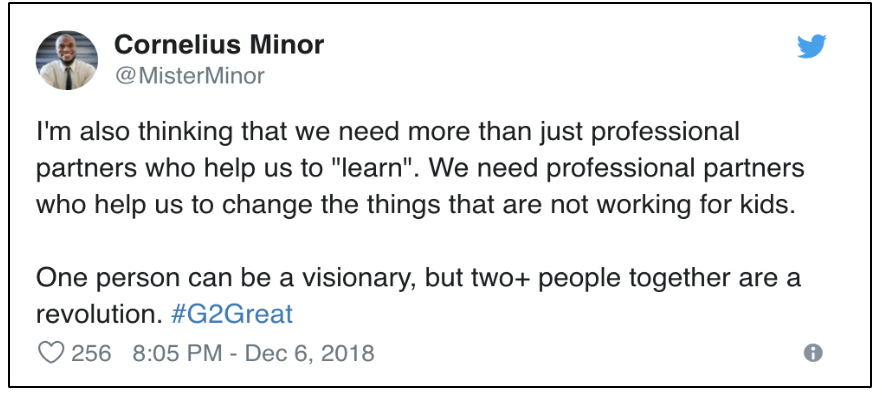

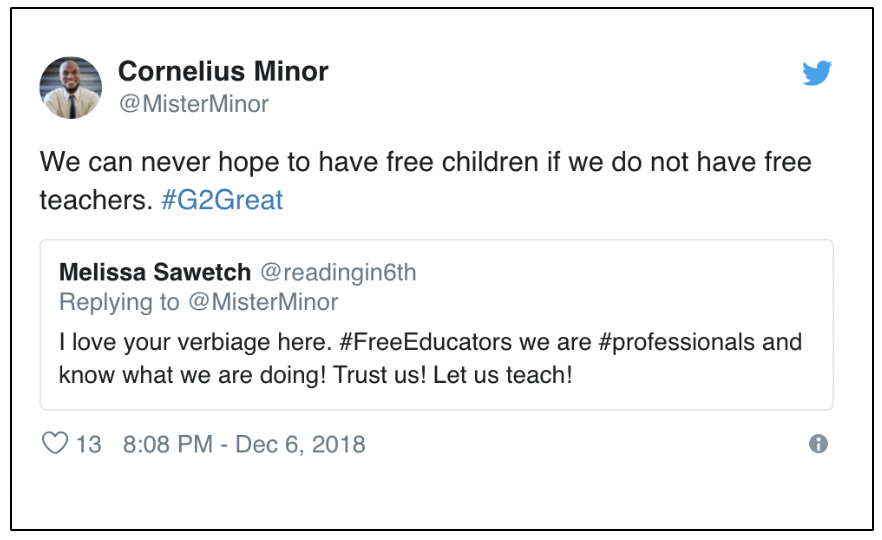

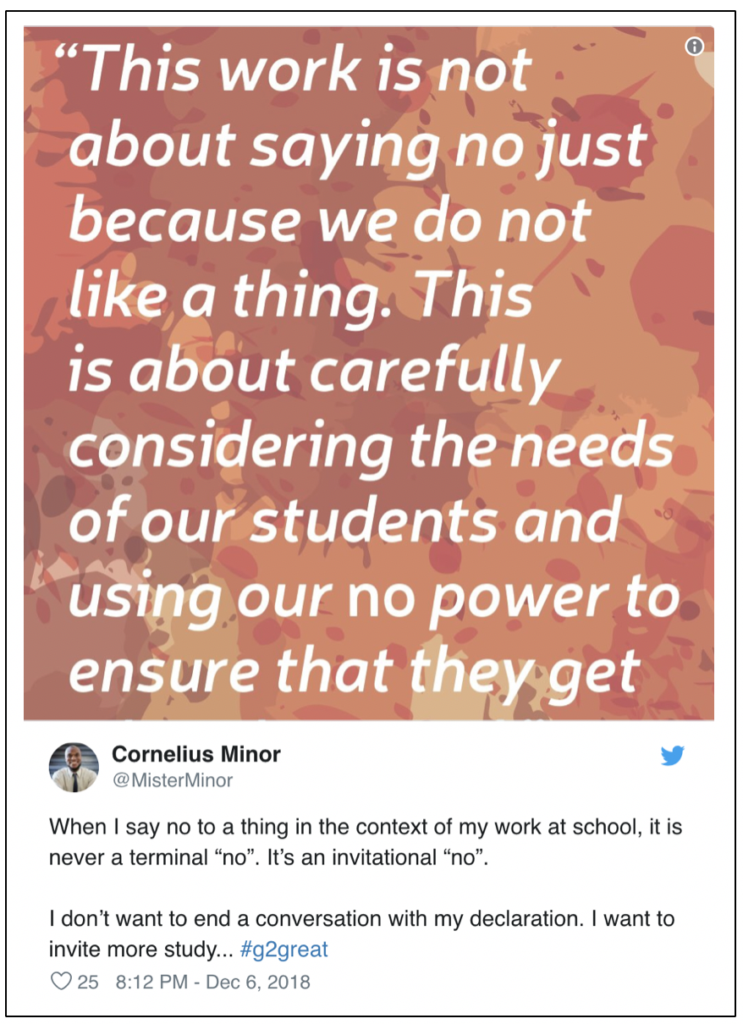

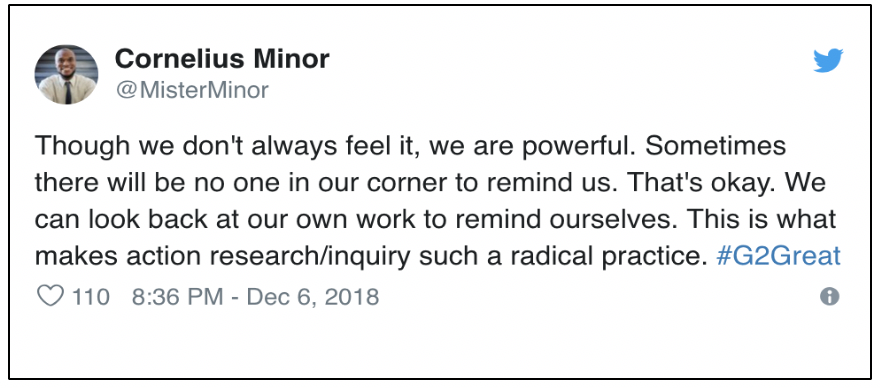

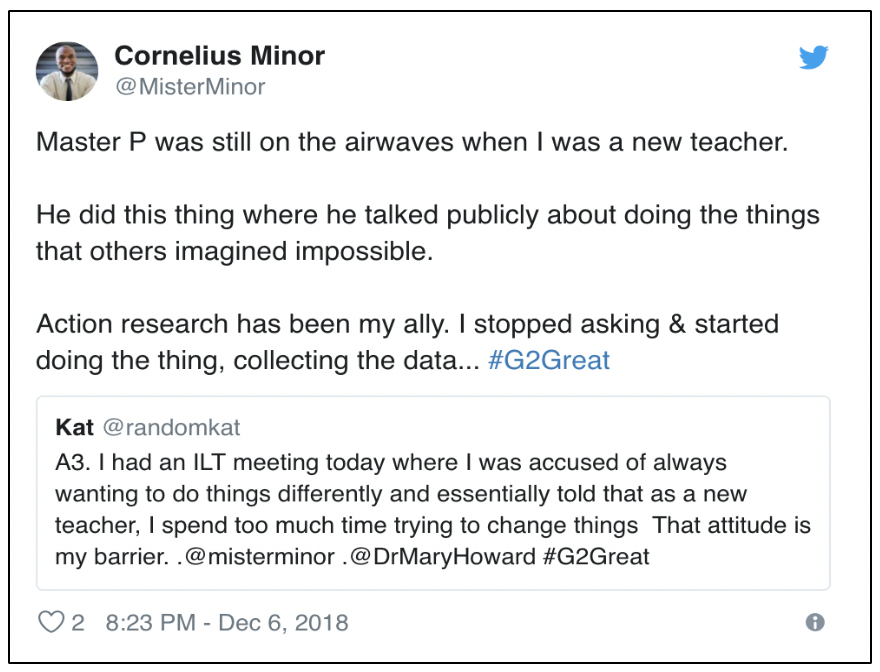

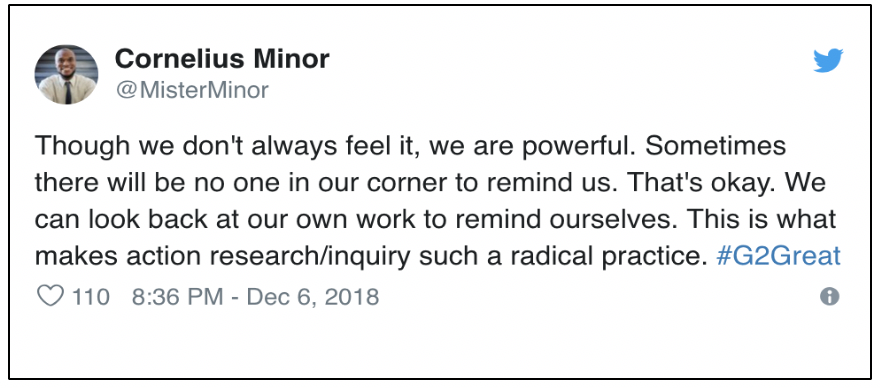

There are several parts to that question. I think first of all that the kind of people who become teachers are the kind of people who were good in school. For the most part that means that you’re a rule follower. That means that you’re compliant. That means you listen when the person in charge says listen. And that mindset is not the mindset that usually gets us to a revolution. So it’s really meant for me looking at who I am fundamentally. I want to do the right thing. If there’s a rubric I want to get highly efficient at using it. And so that’s really what I wanted to do and what I lay out in the book: Here’s how to be a nonconformist in public. The question that I’ve been asking myself more recently is “How do I remain radical and also job secure?” And where does the revolutionary live when you’ve got to pay bills and your kids have to be at dance class at 10:30 a.m.? Where are the spaces for the revolution when you’ve got to pick your kids up by 4:00. I think that really it comes down to our action research. I present action research as the answer. We can look at the practices that are not working for us. We can look at the things that people ask us to do and we can say “No” to those things if we are well researched. One of the things that I am not shy about at all and even the reason I went to Teachers College in the first place and why I left my classroom is that I wanted to get smart enough to protect myself. I am really interested, and this is no accidental use of the term, but I am really interested in weaponizing my research to keep whole communities safe. And I think that as teacher, I can engage in a small inquiry project to give as a practitioner my agency back. Or I can engage in a small inquiry project that allows me to do the kind of work study that I need to do even though my kids are ninth graders and everybody is saying that they don’t need word study.

You ask us to do our homework and then make change happen. You may have just answered this, but are you referring to doing this kind of research in order to arm ourselves with knowledge first?

CORNELIUS

Yes, absolutely. You know, one of the things that I joke about a lot but I really really mean it, is that I enter most fights with my pen. And even on my twitter profile it says “Bring your pens to swordfights.” You know that old saying that the pen is mightier than the sword? I really do believe that applies here. If I’ve got a problem with the policy or if I’ve got a problem with the mandate, I don’t sit in the staff meeting and pout about it and I don’t sit in the staff meeting and shout. I get to work. I’m like, here’s the mandate. Here’s what they want me to do. Is this thing actually going to work in my classroom? Let me go try it. Let me collect my data. Let me think about my results. Let me look at the student work. Let me get student testimonials. And then if the thing doesn’t work I show up with all my data and I’m like “Look this mandate that you gave to us is flawed and here’s how I know. Here’s my student testimonials. Here’s my student work. Here are the things that the parents have said. Here’s the change in affect that I’ve noticed in the school over the two weeks that we’ve been implementing this.” So for me it feels really clear. People always want to say that “Wow Cornelius, you’re so brave. You stood up to that principal. You stood up to that superintendent.” I don’t think that it’s brave. I just know that I trust my data. That when I collect the work. When somebody says, “Hey this thing is proven to work” but then I try it with thirty-five students over a course of two or three weeks and it doesn’t work, then there it is. I think that’s been a big thing.

And have your administrators been open to trusting you?

CORNELIUS

Yeah. It’s been really fun and I’m cautious at the same time too. The book is still pretty young so I’m still seeing what it does in the world. A principal bought copies for her entire staff after reading it. She said, “I realize that this book ultimately teaches people to challenge leadership and that’s exactly what I want for my team.” And lots of principals are buying it. The idea that people are choosing to buy a tool to put in the hands of their teachers that allows them to challenge leadership.

That’s impressive for a leader to do that.

CORNELIUS

It’s actually not when you think about it because it’s who we want. I think that you would want that same thing. There are thirty-two children and there’s nobody better equipped on the planet than me to be in this classroom right now. It’s the idea that when you walk into a room you own the room. With all your imperfections. With all of your insecurities. Yes, every imperfection in me right now is perfectly tuned to this room. And every doubt in me right now is perfectly tuned to this task. That wherever I am, there is some reason why I’m there and I do have something to offer. I hope that teachers feel that way.

With Cornelius’ last words we allowed the interview to come to a natural close since it felt as if this beautifully summed up the We Got This. spirit. Cornelius’ thoughtfully honest responses were so inspiring that I could have talked to him all day but I left our conversation with far more than I ever thought possible. Through his words, Cornelius gives us all a glimpse in the world that he has always envisions. His book, our #G2Great chat and this interview felt to me like the trifecta of POSSIBLE. As I close this post, I am reminded how much care Cornelius put into the idea of listening in his book by devoting an entire chapter to that critical topic.

Well, Cornelius, we are listening and yes, my friend…

We Got This.

Links:

Cornelius PODCAST

Read Aloud PODCAST

Interview Podcast

Cornelius and Kassandra Minor

Video Blogbook release

Contact Heinemann for PD

Cornelius Past Podcasts