Inquiry based learning for students is distinguished by learning that is authentic to the discipline (Wiggins & McTighe, 2008) and, you won’t be surprised to know, that what students discover in the inquiry process leads to an increase in autonomy.

For students, inquiry fosters the construction of meaningful knowledge rooted in essential, disciplinary ideas and skills (Clayton, Kilbane, and McCarthy, 2017).

What’s different is that they have flipped their thinking. Where these educators used to worry about covering the material, they now plan how to evoke kids’ curiosity. When they once focused on assigning and assessing finished products, they now teach thinking: problem posing, researching, vetting, corroborating, analyzing, criticizing, and presenting (Daniels & Harvey, 2009).

It’s important to begin this week’s post about inquiry with a few words from some educational leaders in our field. The remainder of this post, however, will be focused on participant educators and, most importantly, bona fide student practitioners of inquiry.

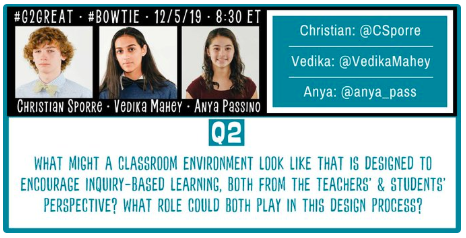

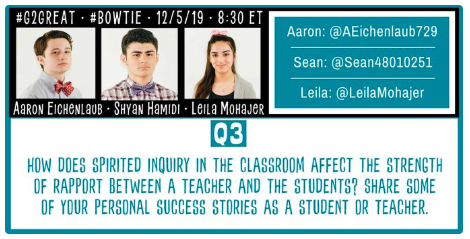

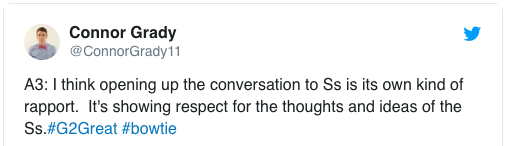

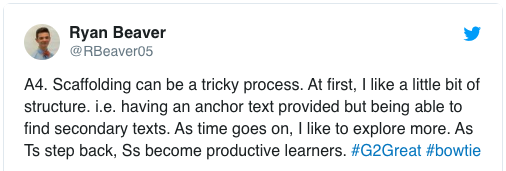

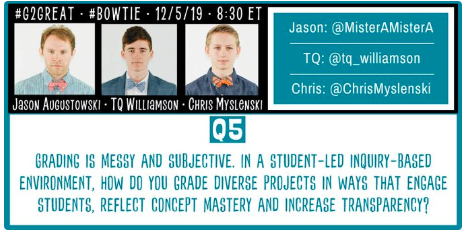

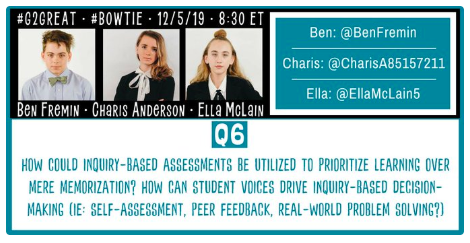

Jason Augustowski and his students led the #g2great chat on Thursday evening. The questions were designed by students and they participated in the chat by responding and raising additional questions to promote reflection on this all-important topic.

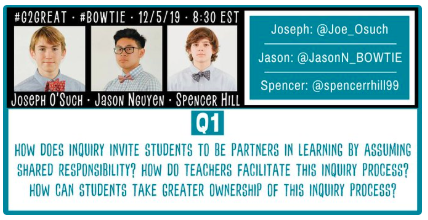

Joseph, Jason and Spencer started the chat by posting questions about the partnership and shared responsibility of inquiry.

In their book, The Curious Classroom, Stephanie Harvey and Harvey Daniels share the origins of inquiry-based learning.

Inquiry learning is no fad. It has a deep history of research and practice in American education. The century-old contributions of John Dewey and William Kirkpatrick built a strong foundation, but other key contributions have come over the past seventy years. Spurred by development of constructivist learning theory and social psychology, the discovery learning movement was born in the 1960s, led by figures like Jerome Bruner. A breakthrough finding of this research was that traditional learning theories could not explain how children learned their native language. Normally developing children invent language structures they have never heard from adults: Daddy goed to work, I have two feets, and so on. This showed us that learners don’t just receive but actively construct knowledge by sampling and actively manipulating the information around them. Not surprisingly, given a hundred years of such study, we can now document improved academic achievement in a variety of settings and grade levels where inquiry-based approaches are in place (Buck Institute 2016).

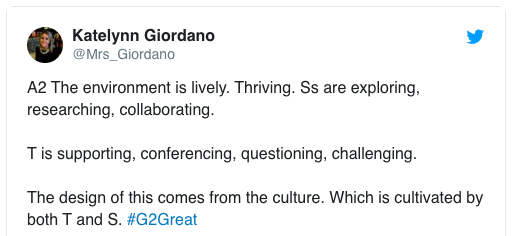

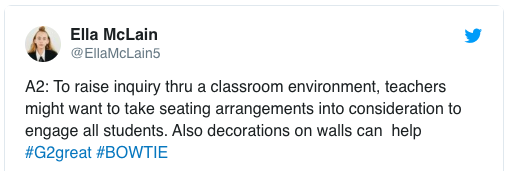

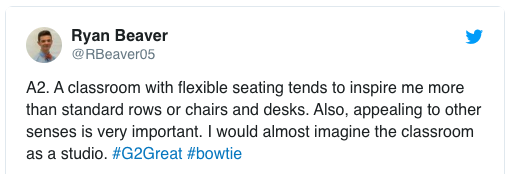

The setting or environment of the classroom is equally as important as the teacher and student dispositions that facilitate inquiry learning.

The physical environment is important, but so too are the relationships in the learning community when committed to inquiry. “Triggering inquiry is about learning something new, and triggering curiosity is no small feat. It takes modeling enthusiasm, and learning something new generates our own enthusiasm, even if it’s something new about the content we’ve covered for years.” (What The Heck Is Inquiry Based Learning? Wolpert-Gowran, 2016)

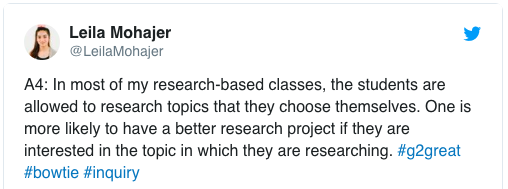

Student-centered inquiry is powerful for connecting “school-work” to real life. It’s also critical for relevant questions by engaged students related to content that lead the learning.

At NCTE just last month, Shea Martin shared during a Friday morning session that teachers must de-center the inquiry process from teacher to center it instead on students. They asked, “How does our own stuff show up in the goals and aspirations we have for our students?” Shea went on to caution teachers in the room to be cognizant of our own baggage and reflect on the way it affects our students. We must think clearly about how we define progress, success, equity, and inclusion, among many other topics, themes and real-life issues. Shea challenged attendees to deconstruct a “selfie-pedagogy” and co-construct the inquiry learning with our students.

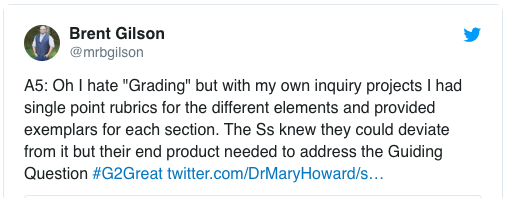

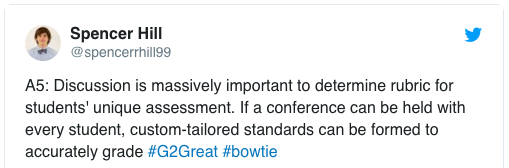

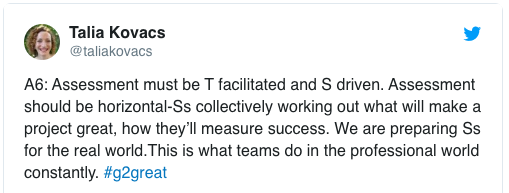

The goal of grading is to evaluate performance. Many assume grades are a way to express student learning, but this widely accepted practice is not the best measure for communicating student growth.

Assessment, however, is feedback that expresses student learning. “Moreover, assessment goes beyond grading by systematically examining patterns of student learning across courses and programs and using this information to improve educational practices.”

In inquiry-based learning students can and should be able to create criteria that clearly communicates growth in thinking, researching and advocacy.

All teachers make choices about how classroom time is spent and what knowledge is privileged. Within critical classrooms, these choices work to empower students. Teachers work with students to deconstruct the world and words around them while constructing words and worlds of their own (Shor, 1999; Freire & Macedo, 1987). This “new literacy,” as Finn calls it, is heir to the tradition of progressive education; it espouses literacy in which the control and the learning shifts from the teacher to the student (Finn, 2009, p. 35). It includes conversations about power and justice, and calls on students to become agents for change (Harste, 2000; Leland, Harste, Ociepka, Lewison, & Vasquez, 1999). (Advocacy at the Core: Inquiry and Empowerment in the Time of Common Core State Standards, Grindon 2014)

The end goal of inquiry learning is for students to engage in content area authentic learning tasks. They must be involved in the creation of essential questions leading to self-directed inquiry.

We are incredibly grateful for Jason Augustowski and the #Bowtie students. The work they are doing is groundbreaking and unparalleled. Thank you, once again, #Bowtie and @MisterAMisterA for leading the learning for the #g2great professional learning network.

We’re listening. We’re learning.

(You can see the other #g2great chats moderated by #Bowtie here.