Please check out the entire #g2great chat, Creating a Common Lens Across Tiers for Explicit Instructional Interventions from 6/13/19 captured on Wakelet here.

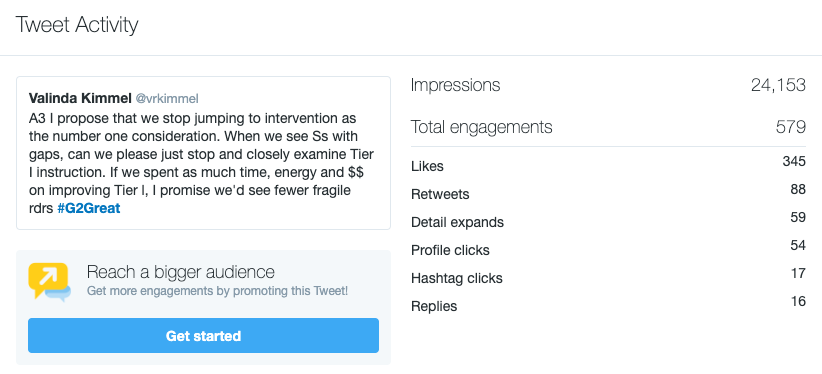

I don’t often start a blog post with analytics from a social media platform, but I’m going to do that very thing right here.

Uh, you think we touched a nerve? 24,153 times this tweet showed up in someone’s Twitter feed. It doesn’t mean it was read, but look at the engagements. Almost 580 people engaged with this tweet.

I’ll ask again. Do you think we touched a teacher nerve?

The focus of our discussion in Part 4 of the series Rethinking Our Intervention Design as a Schoolwide All-Hands on Deck Imperative was on creating commonality in thinking and practice across tiers. That’s a lot of educator-speak, so let me say what I believe that means.

In regard to intervention, every person who interacts with students in a learning environment on a campus must own a shared vision of what it means to support our most fragile readers.

OK.

When we’re about to launch into such a critical issue of a shared vision of intervention across a campus, I want to hear from someone who is an expert in the field. Dr. Richard Allington has written much about this and so I want to take the liberty of quoting him here in this post. The following quotes come from an interview of Allington at Ed Week.

…the promise has been held that we’re going to teach all kids to read. The good news is that, in the past five or 10 years, we’ve had large-scale demonstrations that show that in fact we could do that if we wanted to. We have studies involving multiple school districts and hundreds or thousands of kids demonstrating that, with quality instruction and intervention, 98 percent of all kids can be reading at grade level by the end of 1st or 2nd grade.

So it’s not a question that we don’t know what to do. It’s a question of having the will to develop full literacy in this country, and to organize schools and allocate money in ways that would allow us to do that. Instead, we’ve tended to come up with flim-flam excuses for why it’s not possible.

Richard Allington states that with robust instruction, we can virtually ensure that most students can be reading on grade level by end of 1st or 2nd grade. He offers the solution to that, too. We can and must create literacy instruction and practice with the funds to support teachers to meet the needs of all readers. Can I just say here that once we’ve done that, we will see dramatically fewer students who require some kind of separate support, or in other words, intervention?

We’re not done here because Dr. Allington has more to say–

For the first time in many years, the federal government wrote a law that is not very prescriptive. It simply says: Take up to 15 percent of your current special education allocation and use that money instead to prevent the development of learning disabilities or reading disabilities. And do it in a way that, while there’s no mention of specific intervention tiers, incorporates increasingly expert and increasingly intensive instruction. It’s just telling schools to stop using money in ways that haven’t worked over the past half-century and start investing at least some of that money in interventions that are designed to actually solve kids’ reading problems.

It’s clear from Allington’s statement that we have choice in how to intervene for fragile readers, but he qualifies that by saying, “…incorporates increasingly expert and increasingly intensive instruction.” I understand that to say that our most highly qualified individuals should be using the most effective research-based methods and materials to meet the unique needs of students reading far below grade level.

More from Allington–

For me the most important part of the proverbial three tiers is the first one: regular classroom instruction. In my view, RTI works best if it’s started in kindergarten and 1st grade—we know how to solve those problems. A lot of them (teachers) assume that if a kid is struggling and is way behind in reading, he must have some neurological problem, and therefore it’s not their job to teach him. So you can do a lot by strengthening instruction. The evidence is there in the research literature. We can reduce the number of kids who have trouble in the 1st grade by half just by improving the quality of kindergarten. And by 2nd grade, we can reduce the number of kids who are behind by another half just by improving the quality of 1st grade instruction.

The problem of a packaged reading program doesn’t have any scientific validity to start with, because we know that if you take 100 kids or even 10 kids, there are no prescribed programs that will work with all of them. What kids need are teachers who know how to teach and have multiple ways of addressing their individual needs. And the evidence that there’s a packaged program that will make a teacher more expert is slim to none.

It’s so simple, really. When districts spend time and money on allowing knowledgeable people to write a clearly aligned curriculum and provide their teachers with top tier instructional materials, followed up by systematic training and support for those teachers, then we can ensure kids get the foundational reading instruction that leads to mastery.

I’m currently working as a consultant with a district in my home state as they write curriculum for the upcoming school year. In Texas, we have new state ELA standards and it’s also the year for new ELA adoptions. Imagine my absolute delight when the teacher writers I’m supporting are copiously studying the specific behaviors young readers need to tackle leveled texts as K-2 students, then aligning phonological awareness and phonics resources to the instructional guides. They are also aligning their curriculum documents to include interactive read-aloud and shared reading texts that will engage and model a robust reading life. The district purchased additional classroom libraries for teachers so students will have plenty of texts to choose from as they read independently and with a partner.

This district’s ELA department vision statement includes three powerful words: choice, authenticity, independence. Would you agree that their values align with their practice?

That’s what Part 4 of this series was all about. What can you do on your campus, or in your district to promote a shared vision of what it means to be responsive to every reader’s needs?

Join us next week for the final chat in the series.

Rebora, Anthony. “Responding to RTI.” Education Week, 25 Feb. 2019 ww.edweek.org/tsb/articles/2010/04/12/02allington.h03.html.